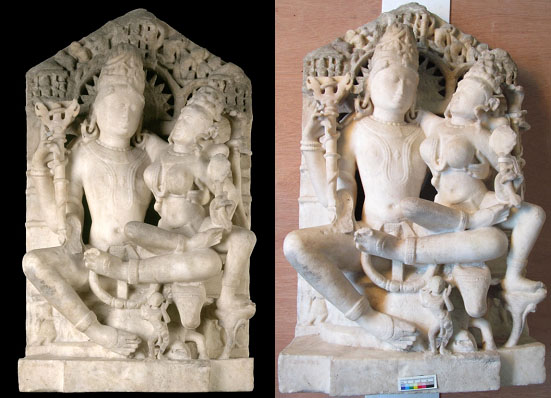

Now on display at the National Museum of Scotland in the Traditions in Sculpture gallery is a wonderful statue of the god Shiva and the goddess Parvati, his consort. The sculpture is of white marble, carved in high relief, and dates from the 11th century CE. It comes from Rajasthan in Western India. Formerly belonging to the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, the statue now makes up part of the permanent collection of National Museums Scotland. In February 2018, the statue came out of storage to the large artefact conservation lab for preparatory work before going on display.

The panel is carved in high relief and portrays a seated Shiva holding on his knee his consort, Parvati. Shiva sits on his vehicle, the bull Nandi. As a pair, they are known as Umamaheshvara, meaning the Great Lord and Uma (Parvati). Shiva represents opposing values: purity and lust, destruction and peace. In this paired aspect with his consort, Parvati, they symbolise together the idea of human, physical love: the union of male and female and marital fidelity. In Parvati’s hand, she holds a mirror to reflect not her own divine beauty, but that of her Lord. Shiva holds a trident, his most typical attribute.

Before carving, sculptors would have to ritually purify themselves, as gods would only inhabit perfectly made statues. The eyes would be finished last; a priest will ritually incise the eye with a golden tool, or a final element of paint. This would turn a carved stone or bronze cast into something else: ‘a divinity who returns our gaze’.

Sculptures like these are used by Hindu worshippers to cultivate devotion and close relationships with the depicted gods.

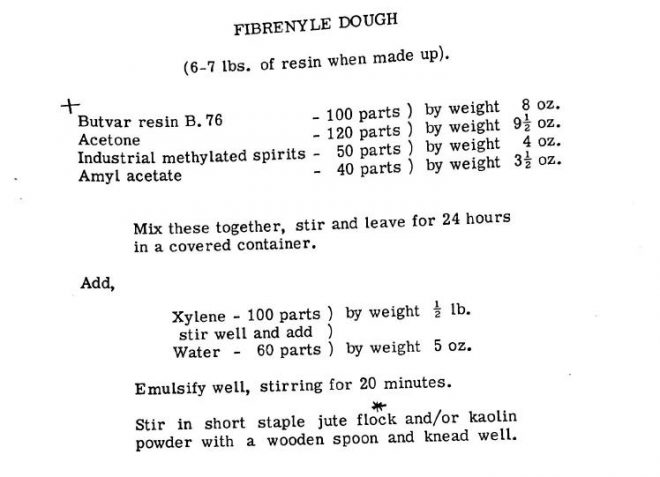

Our Shiva and Parvati statue had previously been restored in the 1970s, when a repair to an old break had failed. The first repair for the old break had used plaster and oil paint. The 1970s restoration involved removing the remains of this and then the break was joined together with an epoxy adhesive. Once the parts were joined together, the break was filled with polyester filler and a substance called fibrenyle dough. Also known as AJK dough, fibrenyle was extensively used in conservation at the Museum in the 1960s through to the 1980s. The fibrenyle dough fill was finished with tinted wax.

The 1970s repair to the statue was still stable and secure. However, due to the long time in storage, the statue had become quite dirty and the repair areas filled with fibrenyle and wax had discoloured and attracted dust. The decision was taken to remove the old fill, clean the statue, and re-fill the break-line with a new modern conservation grade material, which could also be coloured to help it blend into the original marble.

The fibrenyle used to cover the repair fills and break-line was removed by first using cotton swabs of acetone. The acetone softened the dough and allowed it to be manually removed with a sharp scalpel and dental tools.

Once the old fills had been removed as much as they could be, it was time to clean the statue of the dust and debris from storage. The stable surfaces of the marble were cleaned with a dental grade steam cleaner.

Fragile areas, where the marble was sugaring, were cleaned by hand very gently with a brush and a small amount of deionised water. Sugaring is a very common degradation phenomenon of marble, caused by temperature fluctuations. Changing thermal cycles cause micro-cracks to form between the calcite grains of the marble. The marble grains then start to disintegrate and become so fragile that they can be reduced to a sugar-like powder of detached calcite grains just by the touch of a finger.

A residue of an adhesive, from something like Sellotape, on the left-hand side of the sculpture, was removed with cotton swabs of IDA. Once clean, the area was then de-greased with a swab of white spirit and rinsed with deionised water.

Once the statue was clean, the break-line could be filled. A mixture of 2:1 synthetic onyx powder and 25% Paraloid B72 in acetone was used to fill voids along the old repair join and cover any remaining unsightly fill material from the 1970s previous repair within the break-line. Paraloid B72 in an acrylic co-polymer, which is extensively used today in conservation. The onyx fills were then shaped with a scalpel and any excess fill covering the original marble material were removed with swabs of acetone.

A useful characteristic of onyx fills is that colour pigments can be added to tint the fill. Colour pigments and conservation-grade acrylic paint were used with the onyx powder and Paraloid, with the addition of glass micro-balloons, to cap and colour-match the new areas of fill to the surrounding surviving marble. Again, any excess fill and paint/pigments were removed with swabs of acetone.

Once the conservation work on the statue was finished and measurements taken, a custom mount was made by Richard West, an external conservation mount maker from Selkirk. This would enable the statue to be securely and safely put on display.

The newly conserved statue is on display to the public in the Traditions in Sculpture gallery at the National Museum of Scotland.