A stunning collection of over 700 bird fossils has been bequeathed to National Museums Scotland. Collected in Essex by Michael Daniels, the fossils date from 54-56 million years ago, the beginning of the Eocene period. They represent the early stages in the evolution of modern birds and contain many species which are new to science. Andrew Kitchener, our Principal Curator of Vertebrates and Michael’s friend, tells us more about the fossils, their significance, and the dedicated man behind such an important collection.

“Please can you show me your collection of Eocene birds?”

This was the question that greeted me when I first met Michael Daniels more than 25 years ago. Visiting the museum with his wife Pam and his daughter Caroline, this meeting would be the beginning of a long friendship and long-term correspondence.

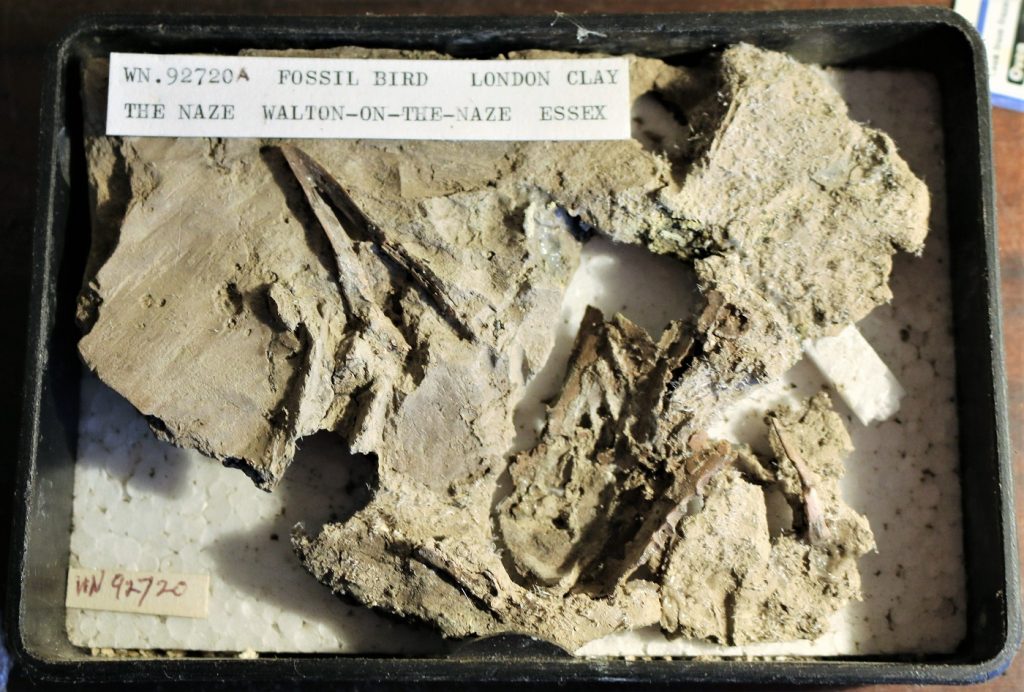

My answer was, “Well I would love to, but we don’t have any.” Michael proceeded to tell me about his remarkable collection of several hundred skeletons and part skeletons that he had discovered in nodules of the London Clay, which had eroded out of the cliffs at Walton-on-the-Naze in Essex.

In later years, I visited Michael and Pam at their home and got to see the collection in its countless drawers and boxes in his study. I was astonished at the amazing variety of specimens of all shapes and sizes. Many of the bones were minuscule, requiring great patience and skill to extract from their substrate.

Work is now underway to fully document and describe the collection. Two papers have already been published describing new species. One is a falcon-like bird and the other is a diver or loon. Experts believe the collection could yield at least 50 new species once research is completed.

But how did this collection come about? Born in Whitstable, Kent in 1931, Michael had a variety of jobs over the years, until he became a self-employed cabinet maker and locksmith. But his one constant passion was palaeontology, which took him to various fossil sites outside London and further afield in southern England from his home at Loughton near Epping Forest.

Michael had a knack to be in the right place at the right time. This led to his focus on a narrow Eocene horizon containing 54-million-year-old bird bones at Walton-on-the-Naze. Previously, only very occasional stray bones had been found there, but Michael discovered hundreds of more-or-less complete skeletons. They ranged in size from the fragmentary bones of a large falcon ancestor (similar in appearance to a predatory phorusrhacid or terror bird) to tiny hummingbird-sized skeletons of a swift.

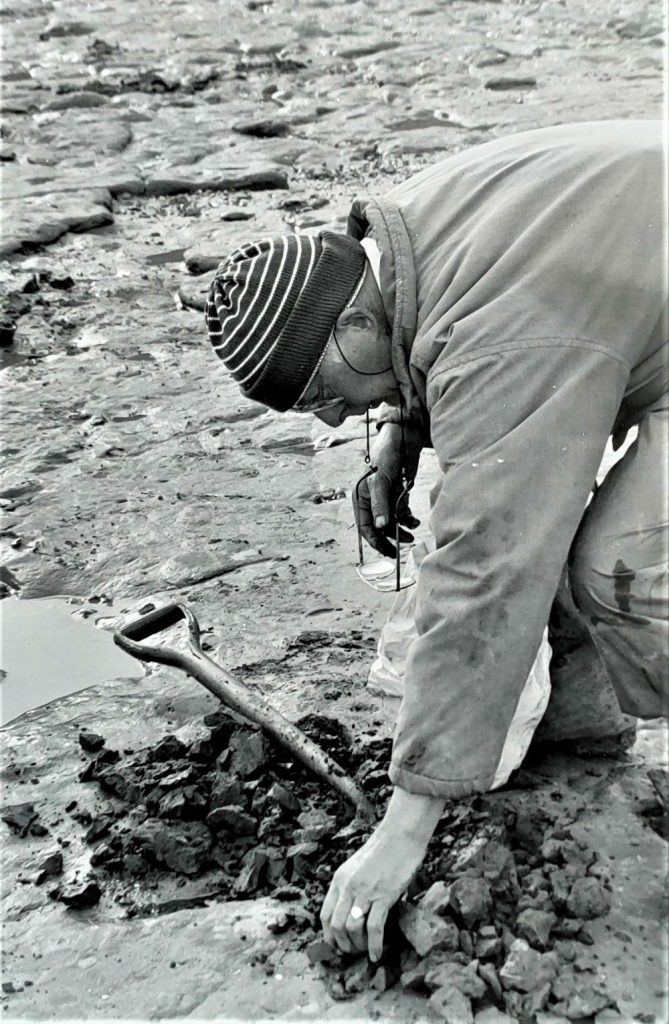

Michael estimated that he drove 27,000 miles and walked 1,590 miles on 640 field visits to Walton-on-the-Naze to collect 15 tonnes of London Clay! He then took another 600 hours or 150 days to painstakingly prepare around 700 fossil bird skeletons.

Motorway development in the mid-1970s of motorways not far from Michael’s Loughton home exposed these Eocene beds inland. His keen observation in the field attracted Michael to small pockets of material most people would not see in otherwise seemingly unremarkable clay beds. He found hundreds of fossils preserved in lumps of clay that had eroded out of the Naze cliffs, but that was only the start of the process.

Extracting, processing, sieving and drying the residues were painstaking tasks. Separating the relevant finds and marrying together fragments into some coherence involved his watchmaker-like skills, a binocular microscope, probes and tweezers. He was even able to extract the middle-ear bones of tiny birds!

An independent, strong-willed and largely self-taught palaeontologist, Michael took great pride in his collection, which he documented and analysed in great detail. He sourced the skeletons of living bird species to help him identify the fossil specimens.

Michael developed his own system of 70 avian skeletal characters (with a total of 270 possible criteria) to score each skeleton and show how similar it was to a living bird species. Despite this, many birds were difficult to classify because they originated from near the beginning of the modern evolutionary radiation of birds and often have characters mixed together that are now found in different modern bird families.

In the Eocene, the climate was much warmer than today. According to a recent study, global mean annual surface temperatures were 13°C warmer than late 20th century temperatures. The fauna from this site may therefore have important lessons for today’s global climate change. Given this warmer climate in the Eocene, it is perhaps not surprising that the former huge diversity of bird species at Walton-on-the-Naze is more like what you would see in an Amazonian rainforest than the Essex of today.

Michael wondered whether a possible catastrophe caused the mass avian mortality at this site. He explored volcanic evidence and the possibility of an asteroid strike. Michael was particularly interested in the origin of some possible glass-like tektites he found at the Naze, which might be evidence of this impact catastrophe. Hopefully further research can settle this question using the small samples of tektites in the collection.

The importance of Michael’s collection cannot be underestimated. Both in the UK, where there is no comparable site for avian fossils, and further afield. Other bird-rich sites include Green River, Wyoming, USA; Messel in Germany, also of Eocene age; and Liaoning, China, which dates to the earlier Cretaceous period. What makes the Naze fossil birds so important is that they are preserved in three dimensions (at other key localities they are squashed flat because bird bones are so light and fragile). They also represent the early stages in the evolutionary radiation of modern birds.

As you can imagine, there has been keen interest in providing a permanent home for the collection from several of the world’s leading natural history museums over the years. Michael resisted all advances. It was only in early 2021 that he finally decided that he would bequeath his remarkable collection to National Museums Scotland.

We brought the collection to Edinburgh on 11 November, having spent a very long day carefully packing each specimen. Sadly, Michael died unexpectedly a couple of months before this on 27 September 2021. It was a sad task to be removing Michael’s collection from his now empty home, but I am sure he was glad that he had made the decision.

We are very proud and honoured to host this collection. It will provide decades of research interest with many new species of fossil bird awaiting a formal scientific description. But the collection also provides an opportunity to study how this wide diversity of birds fits into the wider Eocene ecosystem of what we now call Walton-on-the-Naze. The fact that the collection is now with us here at National Museums Scotland will be of interest to palaeontologists across the world.

The quality of Michael’s collection meant that he’d already worked with several of the world’s leading avian palaeontologists. For example, he collaborated with Dr Gerald Mayr of the Senckenberg Research Institute in Frankfurt am Main on new bird species, such as the parrot-like passerine relatives from the Green River, Messel and Walton-on-the Naze. Gerald has since been to see the fossils in our National Museums Collection Centre to continue working on them.

Sir David Attenborough (anonymously) described Michael’s collection in The Life of Birds. He singled out the “remarkable site” at Walton-on-the-Naze for providing “astonishing evidence of this swift and rich development” of bird evolution “yielding over six hundred specimens of ancient extinct birds.”

The extent of this remarkable fossil assemblage is largely down to one man’s dedication, which Michael summed up in his own words in a short pencil note found recently: “Just a scrap of bone that proved to be bird … that strange but necessary wherewithal and element of obsessive crankiness to keep going and continue searching for 33 years”.

Research on and curation of the collection has already begun. Keep a look out for many more new species of Eocene fossil bird appearing in the palaeontological literature as researchers from around the world get to grips with the enormous diversity of Michael Daniels’ remarkable collection.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank David Bain for his help and hospitality in the transfer of Michael’s collection to the National Museum of Scotland. I would also like to thank David and Bill George for sharing much of the biographical information which I have reproduced in this blog.

You too can make a difference to the future of National Museums Scotland. A gift in your will costs you nothing in your lifetime but allows you to make a lasting difference to the work of National Museums Scotland and the lives of visitors for generations to come. All gifts, large or small, can help protect our collections for the future. Find out more about how you can support us in this way.