Often in life, it’s the small jobs that take a surprisingly long time. This was definitely the case with these ancient Egyptian votive statues I worked on back in 2018. As part of the redisplay of the Museum’s ancient Egyptian collection, these little artefacts were due a quick clean and remount. Some had been on display before, and others kept in storage. But all required assessment and cleaning before the Ancient Egypt Rediscovered gallery opened. It seemed a simple job at first, but some of these wee guys were hiding secrets…

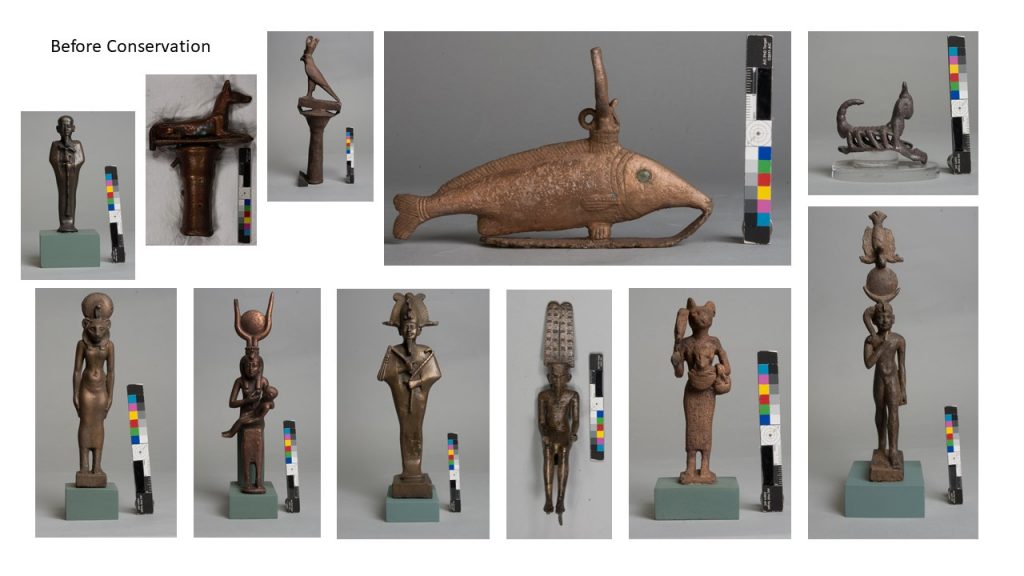

Before conservation

They were originally made as votive offerings, essentially gifts to the gods. All are made of copper-alloys cast in moulds made from wax models. Many have tangs at the base indicating where they were originally fixed to a different support, sometimes of a larger scene with multiple statuettes. They range from a wee statue of a scorpion to a larger statue of the god Osiris. My particular favourite is the statue of a lion-headed woman, depicting the goddess Sekhmet.

Statue of a scorpion.

Statue of the god Osiris.

Statue of the lion headed goddess, Sekhmet.

Before any work was done, I photographed the statues for our conservation records. I also checked our old records for any details of previous conservation work. The statues were acquired by the Museum from different sites and at different times, and so conservation and restoration work will have been conducted at various points along the way of the ‘lives’ of the statues from when they were discovered to when they arrived at my workbench. The Museum has good records of object treatments going back to the 1950s; some statues had records of what had been done to them before, but others didn’t.

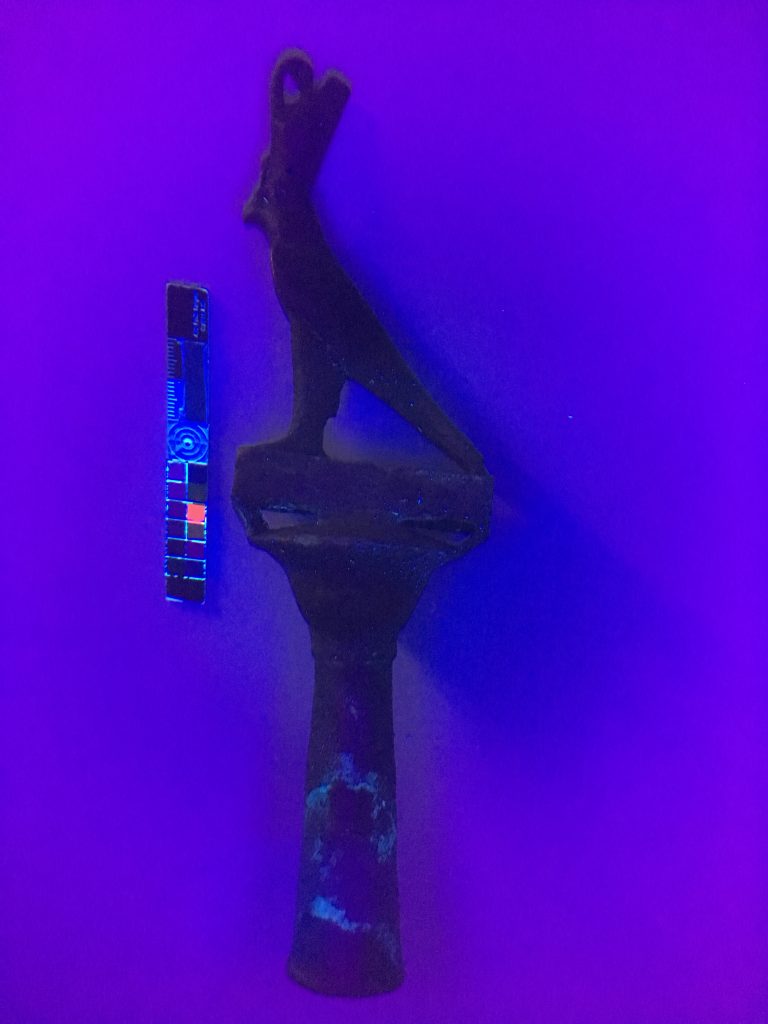

Once I thought I had a better idea of what previous work had been done on the statues, I then examined them under UV light, which revealed old repairs and restorations on some of the objects, like the sceptre-head topped with a figure of the falcon-god Horus. Old fills and coatings sometimes fluoresce under UV light, but not always! It depends on the materials used. This warned me where to take extra care when cleaning the statues.

The old conservation records and UV light did not tell me that there was an unrecorded hole in the sceptre-head hidden under wax. However, when I used a cotton swab with industrial denatured alcohol (IDA) to clean the area, I noticed some pigment on the cotton: an unusual occurrence when you’re supposed to be cleaning solid metal. Further examination revealed an unrecorded hole that had been filled with a material called AJK dough, and covered with wax and pigment. AJK dough softens in IDA, so further cleaning of the object would likely weaken the fill.

Horus statue under ultraviolet light.

I also discovered that the sceptre-head had spots of active corrosion present. The standard treatment of active copper corrosion at the Museum is to manually remove the corrosion with small tools, clean the area, and then fully submerge the object in benzotriazole (BTA) in IDA as a corrosion inhibitor. The BTA forms a layer on the surface of the copper to stop the spread of corrosion. However, I now faced a dilemma: submerging the sceptre head in BTA in IDA would treat the active corrosion, but it would also definitely soften the AJK dough fill, compromising its integrity and possible removing it altogether.

The sceptre-head needed to be treated for active corrosion to prevent its spread, both on the sceptre-head itself and to other objects. I took the decision to remove the AJK dough fill to reveal the unrecorded hole. This was done by softening the fill with IDA and manually removing it with a scalpel and toothpicks under a microscope. I documented my work as I went, in order to update the object record.

Hole in statue before fill.

Hole in statue after fill.

Once the sceptre-head had been treated for active corrosion and fully cleaned, I filled the hole with glass micro-balloons in an adhesive, and then colour-matched the surface of the fill to the surrounding metal with conservation grade acrylic paint. This is a lightweight but strong fill material to provide support to the weakened area of the hole. But it is also easily reversible with solvents, so it can be removed from the object in future if so needed. I cleaned the object again to remove any residue, and finally photographed it for our post-conservation records.

Other statues also had active corrosion present, and so required treatment as well as cleaning. Some of these we already knew about, such as the wee Oxyrhynchus fish standard and the Anubis jackal sceptre-head.

Oxyrhynchus fish standard with corrosion.

Anubis jackal sceptre head with corrosion.

Copper corrosion can be quite obvious on bronze statues: bright green-blue spots! However, corrosion can also hide where only detailed examination can find it. When I removed a statue of the young god Khonsu from its old display base, this revealed a large area of active corrosion on the underside of the statue, as well as small spots of active corrosion on his face, which had been concealed under a layer of wax. These needed treating, which would normally be a relatively simple task.

However, further examination and cleaning revealed that the young man had lost his feet at one point, and these had been re-adhered with an unknown adhesive and the join area covered with wax. To treat the active corrosion, the statue would have to be submerged in the BTA/IDA solution, which would very likely affect the adhesive securing the feet, possibly weakening it and compromising the join. As with the falcon sceptre-head, I made the decision that treating the active corrosion was necessary for the future stability and preservation of the statue. I took down the join with solvents, so that the whole of the statue, both feet and body could safely be treated for corrosion.

Khonsu with missing feet.

Khonsu during conservation.

Khonsu’s feet during conservation.

Once the statue had been treated, I re-adhered the feet back onto the statue and attached small ‘bandages’ of Reemay® to provide support around the back of the ankles. Reemay® is an inert, 100% polyester material which can be colour-matched with acrylic paint and impregnated with a consolidant to provide strength and support. It is also easily removable without damaging the object, in case the statue needs to be treated or studied again in future.

Oxyrhynchus fish standard after conservation.

Anubis jackal sceptre head after conservation.

Khonsu statue after conservation.

Working on these wee statues was fiddly but fun. Surprises are often part of the job of being a conservator, and probably one of the most exciting parts. These statues were great examples of older conservations practices and restorations. Being able to get up close to objects and cleaning them can reveal all kinds of secrets: from how they were made, what materials they were made from, to hidden breaks, losses and restorations. A quick clean uncovered a whole lot in this case!