One of the more spectacular and much loved of the objects in the Egyptian collection at National Museums Scotland is the coffin of the ‘Qurna Queen’.

This polychrome wooden coffin belonged to an unknown royal female of the 17th Dynasty. It dates from the 16th century BC, and was one of my major conservation projects as part of the team preparing the Egyptian collection for the new galleries opening at the National Museum of Scotland in 2019. This blog post is a little history of the coffin and its conservation.

History of the coffin

At the end of 1908, archaeologist Flinders Petrie discovered the intact burial of a young, privileged woman and a child at a site called Qurna by the road to the Valley of the Kings at Thebes (modern Luxor) in Egypt. The woman had been buried in an elaborate rishi-style coffin with an exceptional assemblage of burial goods. These included a collar of gold rings, gold earrings and bracelets, with, among other things, furniture and ceramic vessels, and offerings of grapes, dates, assorted loaves and cakes for the afterlife. At the foot of her coffin was another for a young child; possibly her child or a sibling, who had died at a similar time.

The owner of the coffin is unknown in name, but she was most likely a member of the royal family of the 17th Dynasty. The coffin dates from c.1585-1545 BC. The base of the coffin is gesso-covered and painted sycamore-fig wood and the lid is gesso-covered, painted and gilded tamarisk wood, both local Egyptian species of wood and both hollowed out and shaped from single tree trunks.

The coffin is comparable to known kings’ coffins of the 16th century BC in both form and decoration. The base of the coffin is blue on the exterior with no internal decoration. The lid has feathered patterning painted in blue on a yellow ground with black details. The face is framed with a striped nemes-cloth, a type of royal headdress. Also depicted are a beaded collar with falcon terminals and a vulture-pectoral with outstretched wings. All these details are highlighted with gilding.

The woman was buried with goods indicating ‘a level of wealth that would be notable in any period’ (Roerig (ed.) 2005: 16). Our Analytical Scientist at the Museum, Dr Lore Troalen, has analysed the gold of the woman’s jewellery: the collar and bracelets she was buried with are made from 90% pure gold, while her earrings are 95% pure (Troalen et al 2009).

The woman buried inside the coffin was slender and about 150 cm tall. When she died, she was probably between 18 and 25 years old. The child in the coffin who was buried with her was likely to be 24 to 30 months at death, and the jewellery which accompanied the remains suggests a female child. The presence of two coffins in a single grave also suggests the child was a relative of the woman, most likely a daughter, but possibly a sibling or other relation.

The coffin and burial goods indicate that the woman was an important member of the royal family, either by birth or by marriage. There is an inscription in hieroglyphs down the central column beneath the vulture-pectoral, which was modelled in plaster and then gilded. It reads:

‘An offering which the king gives to Osiris, lord of Djedu, a voice offering of bread and beer, fowl and beef, for the spirit of…’.

What should follow is the woman’s titles and name, but only a single hieroglyph survives. We have been unable to recover any evidence of surviving inscriptions. There is space for several titles, and we can suppose she may have been a queen.

The finest examples of pottery from the burial indicates that the woman or her family had links with the kingdom of Kush, an ancient kingdom in Nubia, located in the southern Egyptian and Sudanese Nile Valley. Analysis of her diet, through the carbon and nitrogen isotypes in her bones, also suggests a Nubian link, that she either had a fondness for Nubian foods or was from Nubia and moved to Egypt as a child (Eremin et al 2000; Manley & Dodson 2010:26). The exquisite pottery may have been acquired through trade or as gifts from Nubia to the royal family at Thebes, or perhaps she was a Nubian princess married to the king of Thebes.

The coffin and whole assemblage were offered by Flinders Petrie to the Royal Scottish Museum (now the National Museum of Scotland) in 1908 and immediately registered and put on display in Edinburgh in 1909. 110 years after it was first put on public display, the coffin has been brought to the Artefact Conservation lab for treatment, before it is displayed in 2019 as part of the extensive re-display of the Ancient Egyptian collection at the Museum.

Conserving the coffin

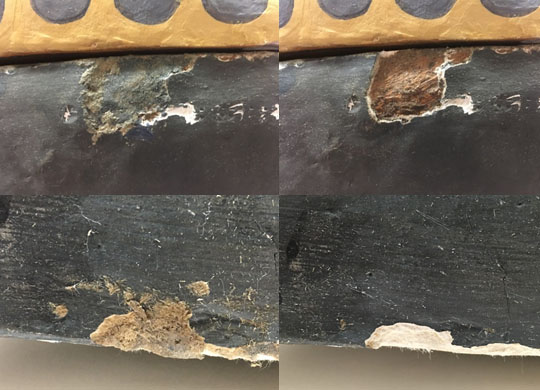

The coffin needed conservation treatment to consolidate the gesso and paint for display in 2019. There were cracks and loose gesso (chalky paint) on both the base and lid. In places, the painted gesso was in danger of separating from the wood underneath, which would have resulted in loss of material.

The coffin had been extensively repaired in the earlier 20th century with in-filling and in-painting spread over wide parts of the surface and covering original paint layers. The in-painting was additionally very obtrusive and did not match the original paint layers, the blue appearing grey/ black. There were old filling materials around areas of loss which were also obtrusive.

The coffin was analysed to identify the probable original materials used by the ancient Egyptians in its construction, and analysis and records have revealed the likely modern conservation and restoration materials. The original pigments used include Egyptian Blue, calcite, carbon and orpiment.

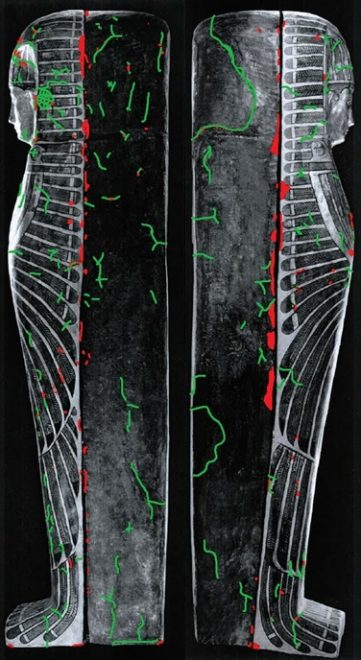

To begin the conservation process, we first needed to fully document the original materials, previous restoration and damage to the coffin. Conservation can be interventive; cleaning can reveal new information, but it could also mean the loss of information. We wanted to get as much information as possible before any work was started.

A team from Historic Environment Scotland (HES) were asked to help us take infrared photos of the coffin to help identify and document the restoration materials. The coffin was further recorded under UV light to help identify the original and restoration areas.

Once all the original material, restoration areas and areas of damage were fully recorded, it was time to start the conservation treatment. The surface of the coffin was first carefully dusted with a soft bristle brush into a variable suction museum vacuum to remove the loose dust and debris from storage and display. To further reduce the soiling from dust, a natural latex sponge and then a vinyl eraser were gently rubbed onto the stable areas of painted plaster, which removes more ingrained dirt.

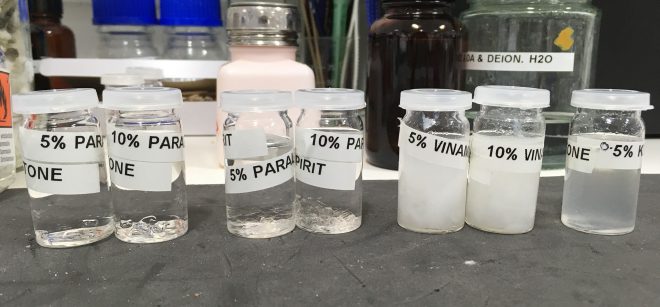

Once the surfaces were clean, I needed to check which solvents would be suitable for use on the coffin with consolidants and adhesives. A small amount of testing was performed to assess how the original materials and restorations would react to solvents. I needed to establish what would be suitable to use without removing original material or affecting any colour changes and which were safe to use in the lab.

Once the appropriate solvents for use were established, consolidants and adhesives could be tested to see which would be most suitable to secure the friable paint and plaster surfaces and to re-adhere in place the loose fragments of the coffin.

The old intrusive repairs to the base of the coffin could be softened with a solvent and then removed manually with small tools.

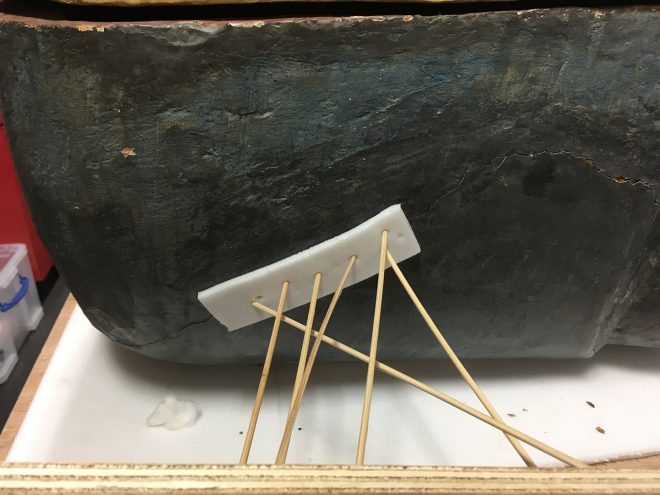

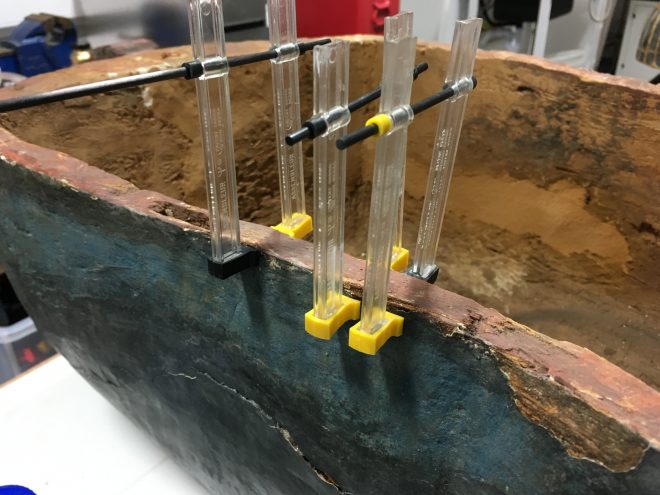

The next task was to consolidate areas of loss and reattach loose fragments of plaster, paint and gold leaf. An acrylic co-polymer in a solvent was used to consolidate and strengthen the edges of loss, and a stronger concentration of the same acrylic was used to secure loose plaster back in place. Loose or peeling gold leaf was carefully adhered down, then pressure gently applied with foam and bamboo sticks in a technique called Shimbari.

Small losses to the paint and plaster were filled with a conservation grade material, which can be painted to match the rest of the coffin.

Detachable fills were made for large losses of paint and plaster along the edges of the coffin. Once made, these were shaped and painted, then adhered in place. These fills are completely reversible and can be removed from the coffin at a later date if needed.

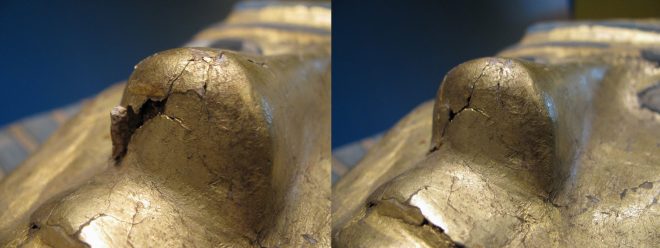

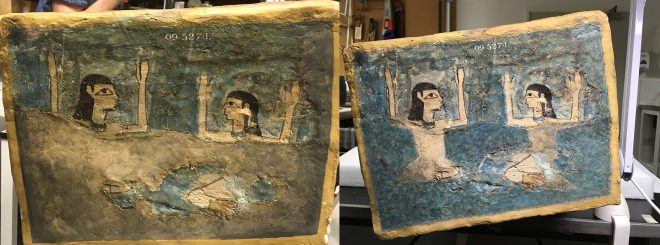

An interesting feature of the Qurna coffin is the decorated foot. The image is believed to depict Isis and Nephthys, the sister-goddesses involved in funerary rites in ancient Egypt. Isis and Nephthys are frequently shown together as mourners; mourning is represented in a number of ways but the raised, bent arm is the most common. The gesture on the Qurna coffin is clearly a little different, and may also have been protective.

The foot of the lid of the coffin had been quite badly damaged during the excavation in 1908 and the area heavily restored in the earlier 20th century. The restoration work on the foot of the lid was quite stable and required little consolidation. However, the paintwork of the restoration was particularly intrusive in colour and was very distracting from the original image. The restoration had either been painted a different colour to the original on purpose, to differentiate clearly the old from the new, or the restoration paint had faded so it was now conspicuous. In consultation with the curator, we decided that for the viewer to better understand the image it would be necessary to retouch the restoration area in a colour more similar to that of the original Egyptian blue.

Now that the conservation is finished, the coffin will soon go on display in the brand new Ancient Egypt Rediscovered gallery at the National Museum of Scotland. You’ll be able to see it, along with many other treasure of the Egyptian collection, from February 2019, the 200th anniversary (May 1819) of the first Egyptian objects entering the collection.

Bibliography

Manley, W. P, & A. Dodson, 2010, Life Everlasting: National Museums Scotland Collection of Ancient Egyptian Coffins.

Roehrig, C. H., ed., 2005, Hatshepsut. From Queen to Pharaoh.

Troalen, L., M.-F. Guerra, W. P. Manley & J. Tate, 2009, ‘Technological Study of Gold Jewellery from the 17th and 18th Dynasties in Egypt’, ArcheoSciences: revue d’archéométrie 33.