In preparation for the major redisplay of National Museums Scotland’s East Asian collection opening in 2019, I have been conserving the ceremonial helmet and armour of Zhang Chaofa, regional commander of the Zhoushan islands, China, from 1830 to 1840.

The ceremonial armour was probably confiscated by the head of British armed forces during the capture of the island of Zhoushan, in one of the first major battles between Britain and Imperial China in the Opium Wars of the 19th century, during the period of the Qing dynasty.

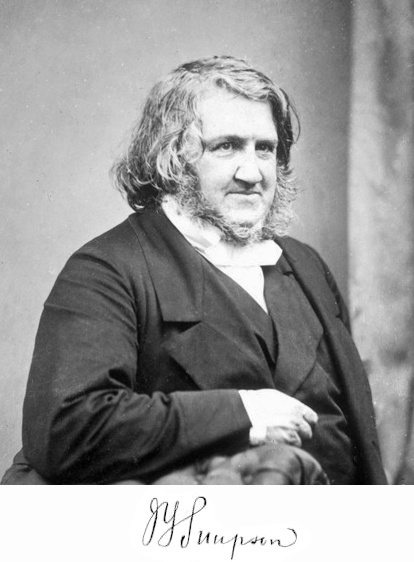

The armour came to National Museums Scotland from the leader of the British forces at Zhousan, Lieutenant-General George Burrell, by way of James Young Simpson, the Edinburgh-born doctor and medical pioneer, when he donated it to the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland in 1860. It became part of the permanent collection in 1956.

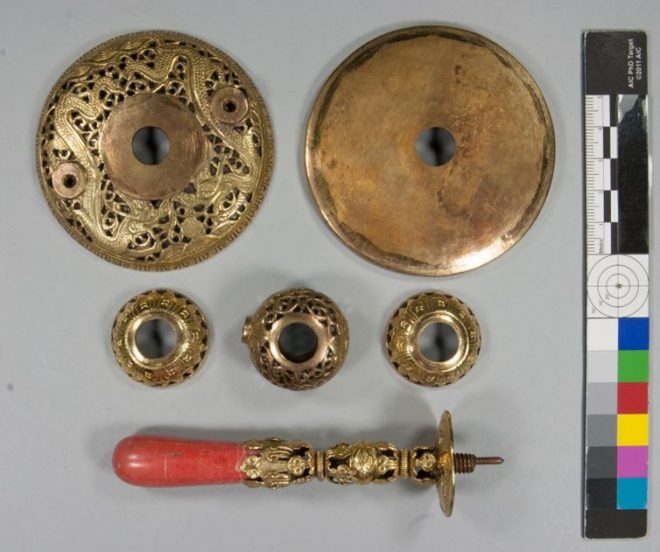

The helmet for the suit of armour is made up of a silvered metal cap with gilt copper-alloy mounts decorated with dragons and phoenixes. A gilt metal dome sits on top to hold an elaborate plume, and a curtain of gold brocade, bordered with black velvet and ornamented with copper-alloy studs, hangs underneath to cover the neck. Lining much of the helmet and armour decoration are gold and silver papers. There are four detachable four-clawed dragons that sit front and back of the helmet, and two phoenixes which flank either side – all are made of gilt copper-alloy.

Other examples of similar types of Qing helmets and armour in Britain are at the Royal Armouries, Leeds, and the British Museum.

For the front and back of the helmet there are two elaborate copper-alloy attachments in the shape of dragons, with twisted gilt and silver wires, glass and paste beads, gilt paper and silver gilt tails, leaves and scrolls with diancui decoration. Literally meaning ‘dotting with kingfishers’, diancui is an ancient Chinese decorative style which uses kingfisher feathers glued onto silver gilt. The effect is rather like cloisonné enamel use in Europe, but with an even more striking blue colour.

Kingfisher feathers have no blue pigment in them; they are actually brown in colour. The blue we see is a result of structural colouration. The blue barbs of the feathers contain spongy nanostructures with slightly different dimensions, causing different reflectance spectra. The feathers scatter blue light by a process called the Tyndall effect: the structure of the feathers reflects back blue light, which reaches our eyes and leads us to perceive the familiar blue. This is the same process by which we see the sky as blue.

The armour consists of a tunic, skirt, skirt front, shoulder pieces, arm pieces, and square pieces of gold brocade with blue silk and black velvet and embroidery, and two circular medallions of silver metal. As an artefact conservator, I have been working on the metalwork and attachments for the helmet and armour. A textile conservator, Danielle, has been working on the brocade, velvet and silk of the armour.

![The right shoulder attachment of the armour, with gold brocade, blue silk, black velvet, copper-alloy studs and gilt decorative attachments, before conservation.]](https://blog.nms.ac.uk/app/uploads/2018/07/A.1956.522.16_2018.BC01-1024x852.jpg)

When it arrived in the Artefact Conservation lab this spring, the metalwork of the helmet was in a fair condition overall. There were some tarnishing and spots of corrosion on the copper-alloy elements, and a lot of surface dust from storage. The helmet had previously been lacquered, as revealed with UV light.

The kingfisher feather details of the diancui decoration and silver ornaments were looking a lot worse for wear. There was much surface dirt and dust obscuring the details of the decoration and concealing the kingfisher feathers, preventing their blue reflectance. There was a significant amount of loss of kingfisher feathers too, with some feathers being stuck back on at odd angles, and evidence that losses had been ‘repaired’ in the past with green paint/paste.

After testing, the old iridescent lacquer was removed from the silver metal surface with cotton swabs of acetone, and then the main body of the helmet, gilt metal dome, brass mounts and studs were surface cleaned with cotton swabs of alcohol and deionised water and degreased with swabs of white spirit. Surface cleaning revealed, hiding underneath all the dust, red-painted paper on the peak of the helmet and gilt paper in between the decoration of the gilt dome. The gold decorated paper surfaces between the decorative elements of the peak of the helmet and gilt dome were cleaned with swabs slightly moistened with alcohol and deionised water, under magnification. The red painted paper was dusted with a soft hair brush and vacuum tweezers.

Some of the gilt copper-alloy attachments for the helmet and armour were suffering from spots of corrosion and accretions. These were manually removed with a scalpel under magnification and the areas of corrosion treated with a corrosion inhibitor before being sealed with an acrylic consolidant.

The tarnish on the silver medallions was treated with a Pleco pen. This uses electrolytic reduction to reduce the silver sulphide tarnish back to silver metal. This means abrasives, a common way to remove tarnish, do not have to be used and so no original material is lost.

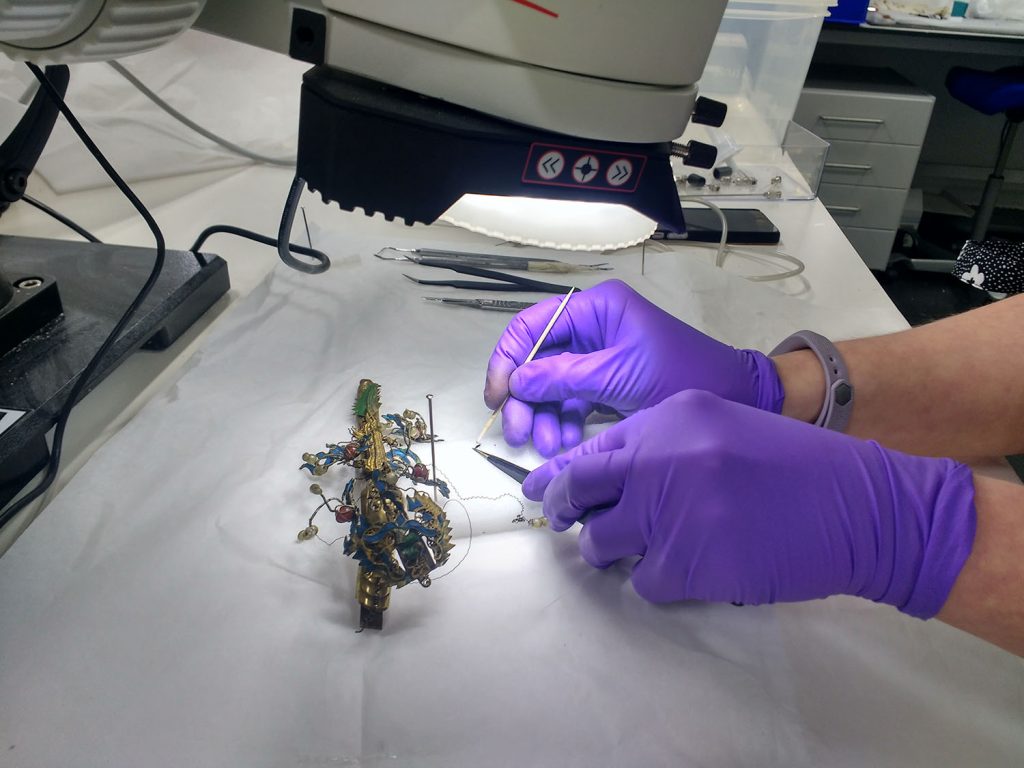

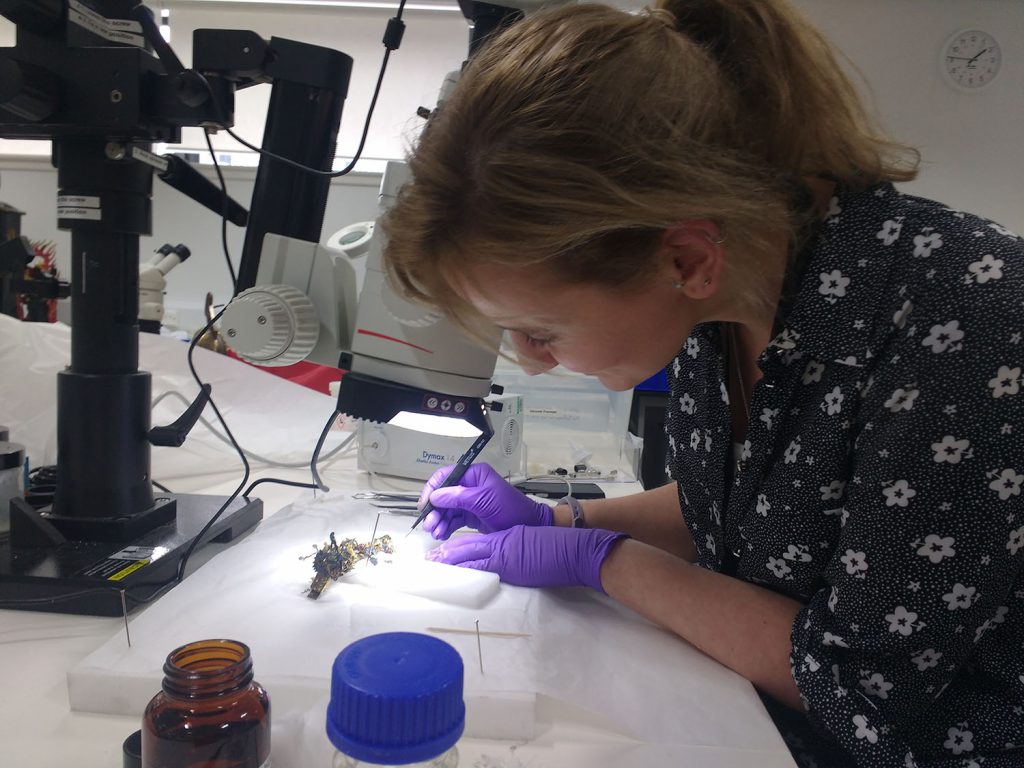

The elaborate diancui dragon attachments were the trickiest parts to conserve for the helmet, comprising many different elements which needed to be treated individually. The kingfisher feathers were cleaned under the microscope with cotton swabs and soft sable brush moistened with alcohol and deionised water.

The feathers pulling away from the metal attachments were reshaped by wetting them with deionised water the manipulating them with tweezers and vacuum tweezers. Once clean and their original blue iridescence revealed, the feathers were consolidated and re-adhered in place to the metal surface. The twisted wire coil decorations were carefully detangled from the main copper-alloy body of the dragon attachments and those wire coils which had come loose were recoiled.

The small glass and paste beads, wires and copper-alloy elements were all cleaned with cotton swabs of alcohol and deionised water, and the gilt paper surfaces cleaned with cotton swabs slightly moistened with deionised water. The underside of the attachments are lined with paper, so these paper surfaces were dusted with a soft sable brush to remove dirt and debris. The lifting paper edges were re-adhered to the underside of the copper-alloy body with methyl cellulose in deionised water and alcohol. One of the diancui dragon attachments had a detached tail decoration, and so this was reattached to the wire under the main body of dragon with acid-free polyester fabric adhered around the wire to strengthen the join.

Next to conserve for the helmet was the elaborate plume attachment, which secures to the top of the gilt dome. This consists of heavily ornamented gold and silver gilt copper-alloy, silvered paper, glass beads, bamboo cane, marten fur, coral, eagle feathers and more diancui. This was dismantled to allow a thorough assessment and treatment of all the various materials.

As with the rest of the helmet, the gilt copper-alloy elements of the plume were cleaned with solvents and any active corrosion removed and treated. The kingfisher feathers on the copper-alloy were cleaned, consolidated and reattached where loose. As with the helmet attachments, this was a very fiddly business which required a lot of time hunched over a microscope. But the change in colour from dusty feathers to clean was wonderful to see. The silver paper was dusted with a fine hair brush and dry cotton swabs, and any loose paper was re-adhered back in place onto the inside of the gilt copper-alloy domes. The marten fur was dusted using a hairbrush and museum vacuum on low suction, with the nozzle covered with gauze to prevent any loss of material.

During cleaning, one of the threads of glass beads became loose. This thread was strengthened and reattached to the bead net with new cotton thread, of near similar colour, which was tied to original thread, wound around and bound to it.

The eagle feathers were cleaned with a soft brush: they were brushed in the direction of the growth of feathers towards a museum vacuum cleaner nozzle, covered with a piece of gauze, on low suction. The feathers were first manipulated by hand to rearrange the barbs back into place. Further manipulation was done after the barbs were relaxed by light steaming, and then straightened into their proper place. Feathers are a keratin material, a type of protein, and chemically related to hoof, horn, scale and nails. The protein chains of keratin are associated to each other by hydrogen bonding and most hydrogen bonds are interrupted at 40 to 60°C, which is why steam is often used to relax keratin materials. Fragile barbs at the tip and near the stem of one feather were strengthened by attaching them to a neighbouring barb with tiny spots of adhesive, performed under a microscope, to prevent their loss.

Once the conservation treatments were complete, it was time to reassemble the helmet and plume and see the diancui decoration in all its blue glory.

To see the completed conservation work, come and see the helmet, the rest of Zhang Chaofa’s armour and other treasures from China and East Asia when our new Exploring East Asia gallery opens at the National Museum of Scotland on 8 February 2019!

Find out how you can be part of the story of our new galleries by donating to our Museum Transformation appeal here: www.nms.ac.uk/transform.