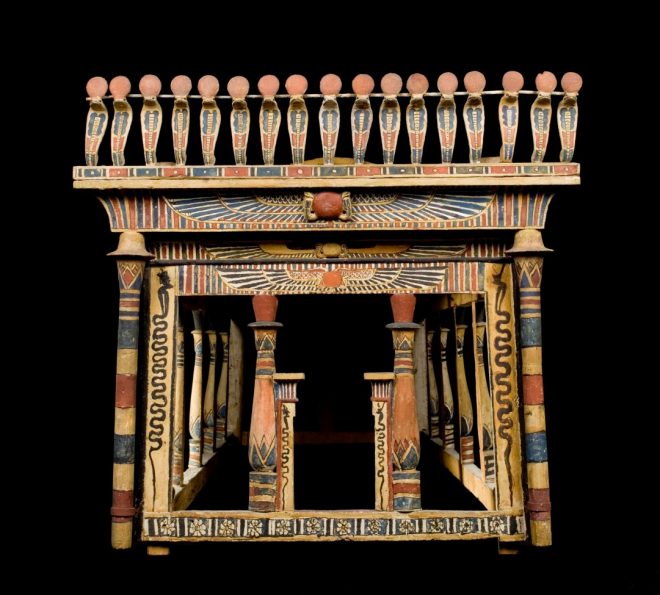

One of the highlights of conserving objects for The Tomb: Ancient Egyptian Burial was having the privilege of working on the rare and unusual funerary canopy, dating from around 9 BC. The canopy is constructed from Sycamore-fig wood and decorated with painted gesso, which is extremely fragile and prone to losses.

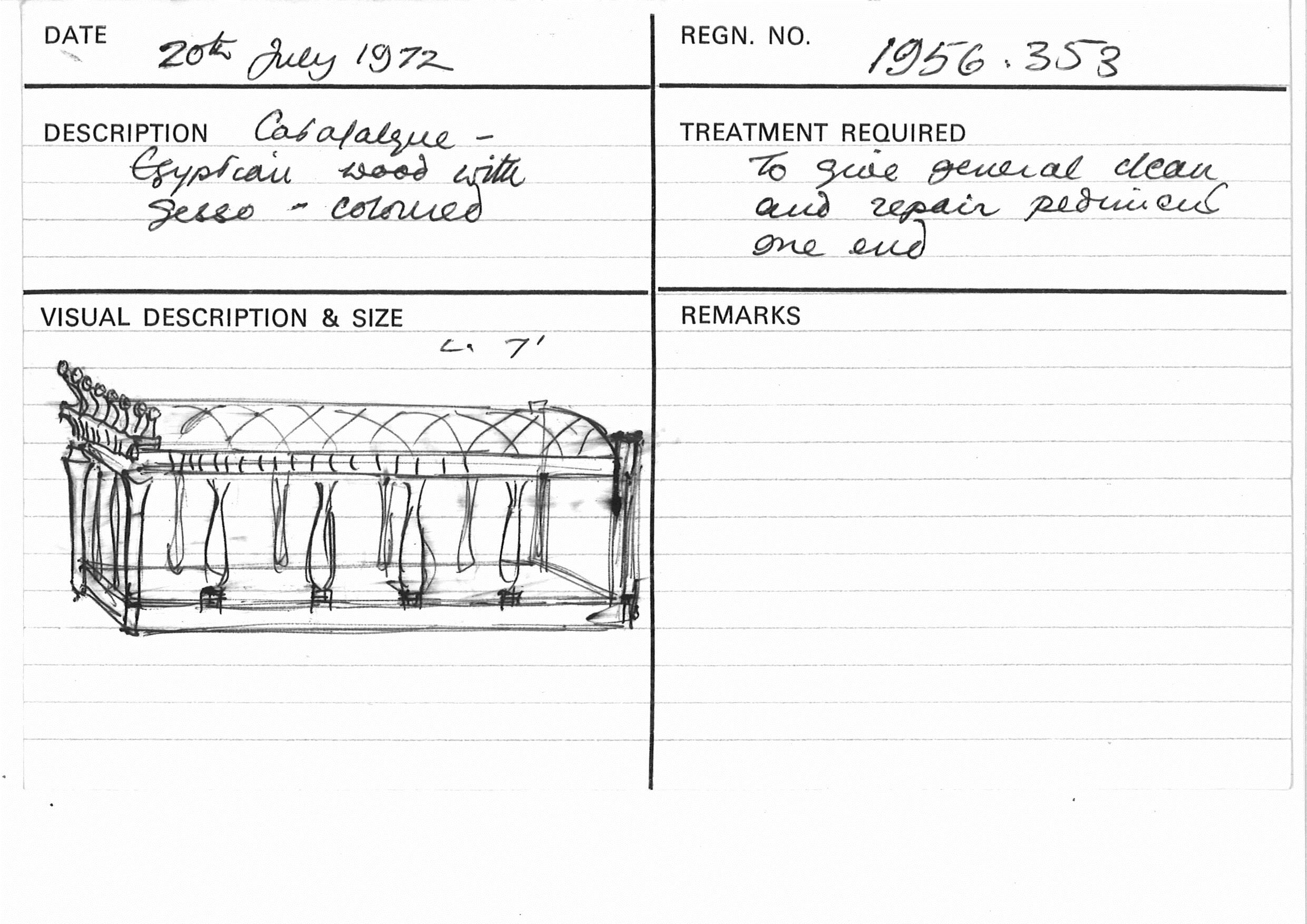

When working on an antiquity, one of our first jobs as Conservators is to examine and determine not only the condition of an object but also what it is originally made from. This can be done by straightforward visual examination, in addition to referring to historic treatment records held in our archives.

There were visual signs that the canopy had undergone extensive museum restoration, with a lot of the gesso decoration having been repainted, but there was very little archival documentation to explain what had been restored and when it had been done.

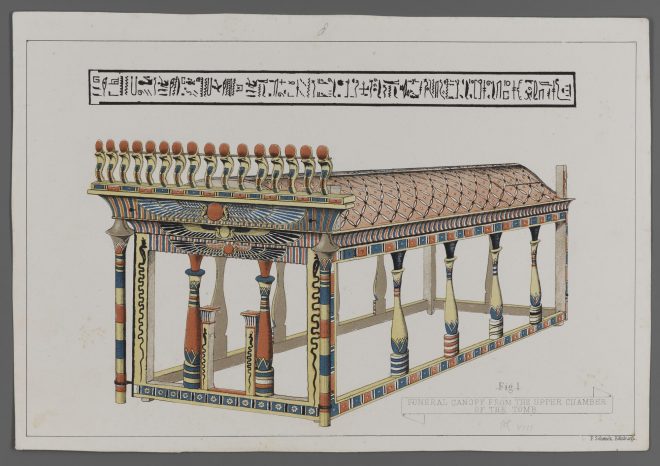

Only two sources of information give clues to the condition of the object at certain points in time. The first is the original illustration of the canopy, published in 1862 in Alexander Henry Rhind’s book, Thebes, its Tombs and their Tenants Ancient and Present.

The 1862 illustration depicts an intact canopy much as we recognise it today. It includes some fine details that suggest it can be taken as a highly accurate representation of the state of the canopy in 1862, and that the canopy was in good condition.

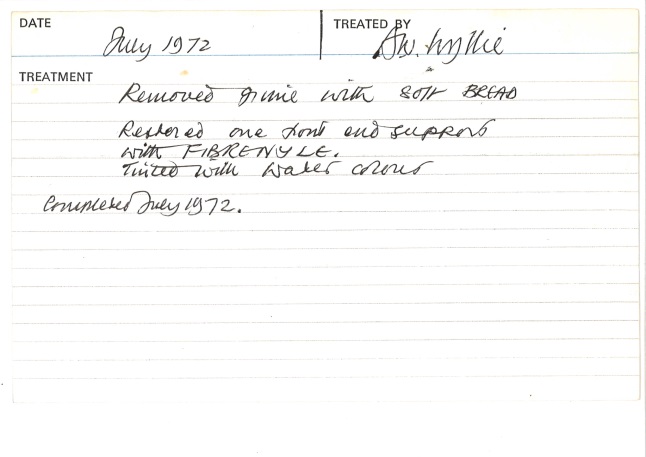

The second follows over 100 years later and consists of a small conservation treatment card written by Conservator Arthur Wyllie in July 1972. The record in terms of treatment is very brief, limited to basic cleaning (using stale breadcrumbs!), and some minor repairs (with no indication of major interventions such as repainting). So when this repainting was done and by whom still currently remains a mystery.

Therefore, the main focus of our conservation treatment was to attempt to map and record the extent of these restorations. As much of the restoration was blended in with the original paintwork, this is hard to determine under normal lighting conditions. The restorations themselves are generally stable and in this case, it could potentially be more damaging to the original material to remove them.

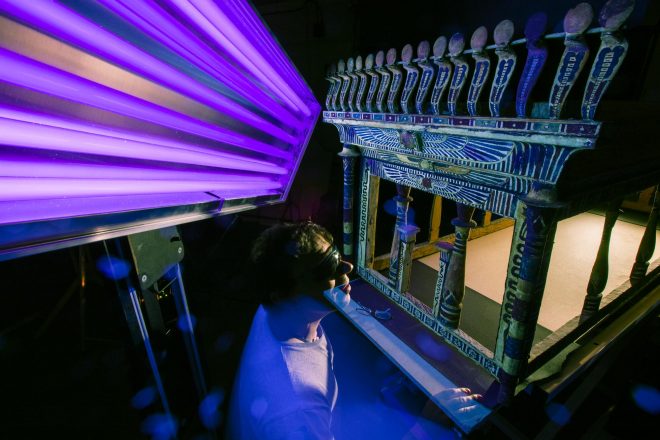

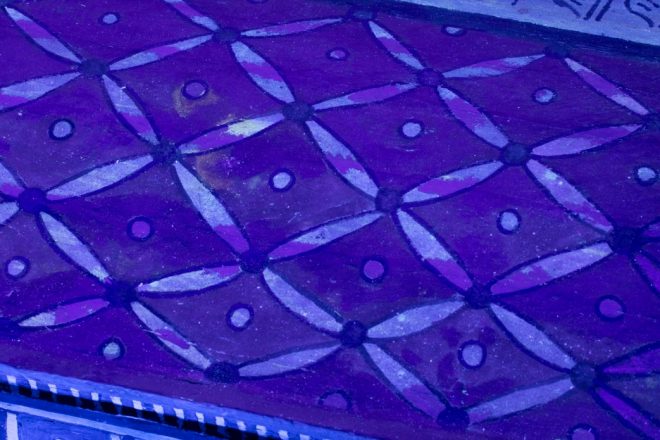

Looking at the canopy under ultraviolet (UV) light allows the extent of restoration to become far more obvious, and by collaborating with Neil McLean (Photographer at National Museums Scotland), we were able to produce high-quality images which highlight the restored areas. UV light is a very important tool for Conservators: it can be used to identify organic substances or differences in an object not visible to the naked eye. Surface coatings such as varnishes and some paints fluoresce under UV light in various colours.

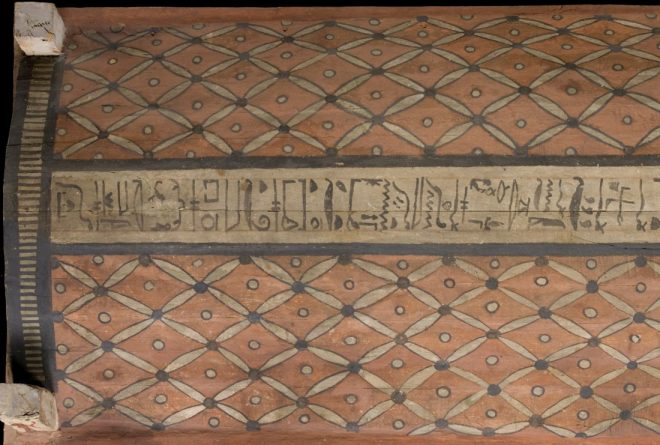

This is highlighted by comparing these two images of the end of the canopy below. The first shows the canopy in normal lighting, the second under UV. Under UV, restorations and repainting appear here as darker purple areas, most notably the cobra carving third from the right, which is a complete modern replacement.

The tops and shafts of the two outer turned pilasters: in the 1862 drawing, the curves of these pilaster tops are more accentuated and the evidence of restoration in these locations seem to suggest that they have been cut down.

One concern was to what extent the unknown restorer may have painted over the hieroglyphic inscription that runs along the roof of the canopy. It is quite possible that they repainted the inscription or emphasised the legibility of the characters using the 1862 illustration as a template. Fortunately, the inscription was largely untouched, with only small localised restorations at one end, observed under ultraviolet light.

Lastly, looking at the end sections and the roof in its entirety, UV light shows up extensive repainting and treatments. The end elevation shows a large area of light purple over the white background of the semi-circular panel, which indicates that this background colour has been repainted.

The process of examining the canopy and uncovering the extent of the restorations has thrown up a lot of questions about who, where and when the restorations were done. The process of writing and keeping conservation records (which is now a critical part of our job as Conservators), only truly began at National Museums Scotland in the early 1950s. We have a large gap in our knowledge of what has happened to objects in the past, and it is essential for us to have these examination techniques available to help fill those gaps and shed new light on our collections.