“Compassion emerges from imagining the world alive.”

These are the words of Alexandra Horowitz, in a book called On Looking: Eleven Walks with Eleven Experts. Horowitz explores the way in which we can become more present in the daily quotidian, by stepping a familiar route alongside the footsteps of eleven different people, some experts like geologists, but also her toddler and her dog. With these fresh eyes alongside her, it is possible for previously unseen elements to emerge. As they share what excites them – from the cracks on a pavement, to the font selected for a sign.

Earlier this year I was also lucky enough to follow in some different footsteps, although whilst on a tour of some unfamiliar grounds – the National Museums Scotland Collection Centre. I came away with my mind afresh with new perspectives and new things to try to see when looking around me. It’s Doors Open Day at the Collection Centre this weekend, our tours were fully booked and so we have now welcomed many more feet to explore the collection further.

Much like our museums, the Collection Centre is a place of dizzying wonders. It provides a home for many of the objects and specimens that are not currently on display in our museums. It definitely has a special charm about it.

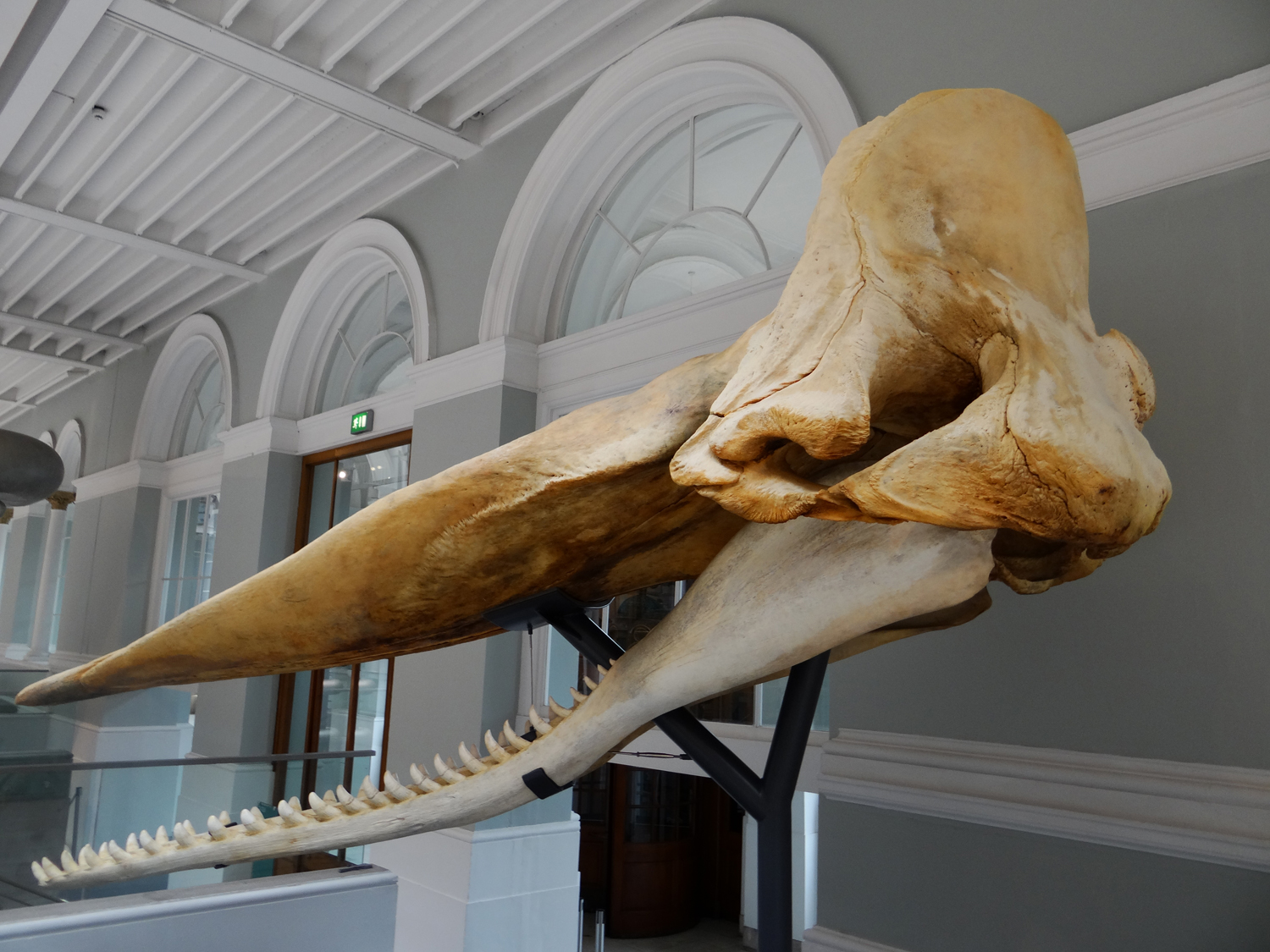

It is only once you step inside the collection stores that the visual impact of each storage space hits you. I personally got rather excited by seeing the vast collections stored side by side in what seems like endless cabinets, drawers and shelves. With objects that range in size from a beetle measuring less than a millimetre (the Nephanes Titan beetle), to the 5.2 metre-long skull of a sperm whale. From butterflies to dinosaur bones, motorbikes to traction engines – the material gathered here is as diverse as it is vast.

However, another attraction of this centre is the view it gives into many different hives of otherwise unseen museum activities. The Collection Centre has facilities for undertaking research on collections, as well as conservation and scientific research laboratories. Much of this research and conservation is what keeps the collections very much alive and in part, what makes the Collection Centre so fascinating and valuable.

On my visit, we visited the departments of Natural Sciences and Scottish History and Archaeology. Neither of which am I expert in, not even close. Yet, I always have a keen interest to continue learning more and more about the world that surrounds me, so these proved to be a good mix.

Entomology

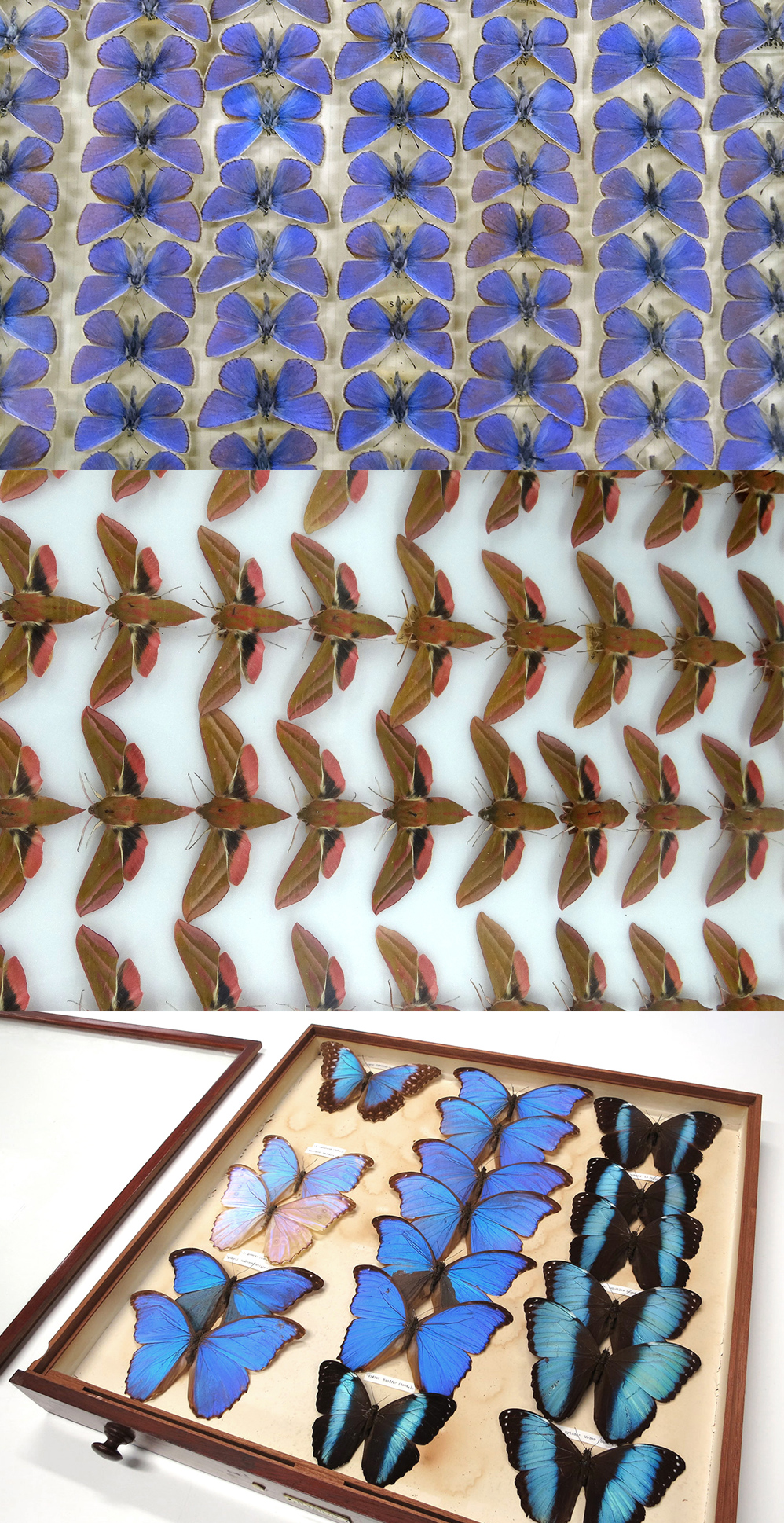

We started with Entomology. In this section we were able to view a collection of beautiful butterflies. On first glance it was a purely visual experience. The striking visual beauty of seeing the spread of many wings was a real delight. I loved the delicate, but colourful nature of their wings displayed in these carefully constructed display cases.

What surprised and delighted me about the visit to this department was not simply the flashy, fluttering butterflies. It was that I also found a form of beauty in the uniform nature of other specimens that had been collected. Like box after box of beetles carefully pinned in place…

The large spiders had some form of appeal. I’d normally run in the other direction if I saw one of these, so to be able to study it up close was refreshing. Some of these samples are over 250 years old.

Whilst in this section, Ashleigh Whiffin, Curatorial Assistant of Entomology, shared that there is much more to notice here than what can initially be seen. These many tiny fly samples highlighted the dedicated and detailed work of researchers. There is ongoing research that takes place in this department and one of the specialists completing his PhD has described some species that are new to science with these samples.

Vertebrae Palaentology

We were then joined by Dr Nick Fraser, Keper of the Department of Natural Sciences, who specialises in vertebrate palaeontology. He took our eyes on a giant leap in scale, as we went to visit the whale room. He shared with us how important our whale collections are in shaping our understanding of the natural world. As ongoing research into changing behaviours and species helps to inform on many issues, like what’s happening with climate change.

There is something quite humbling about seeing the scale of some of these whale bones. It reminded me of a fun project we did back when I was in primary school (many, many, many years ago), where the class created a life-scale drawing of a blue whale in the playground in chalk. It was enormous and we were all amazed at the size of this mighty mammal.

In this earlier blog, Dr Andrew Kitchener shares some of the process that has lead to the collection of some marine specimens and the tough task they had of collecting the skeleton of a 7.8-metre-long male killer whale that had been stranded on the shore below the Rangehead, near West Gerinish.

You can also see the skull of Moby the Whale in the Grand Gallery at Chambers Street. This 40ft whale was sighted swimming up the Forth rather than out to sea back in 1997. Rescuers, including BP tugs and the pleasure boat Maid of the Forth, tried desperately to push him back out to sea. Unfortunately their efforts were in vain and sadly Moby beached and died on the foreshore at Airth on 31 March 1997 – the first sperm whale to be stranded in the Forth in over 200 years. Following his death, Moby’s skeleton was prepared by museum staff, before going on display.

Scottish History

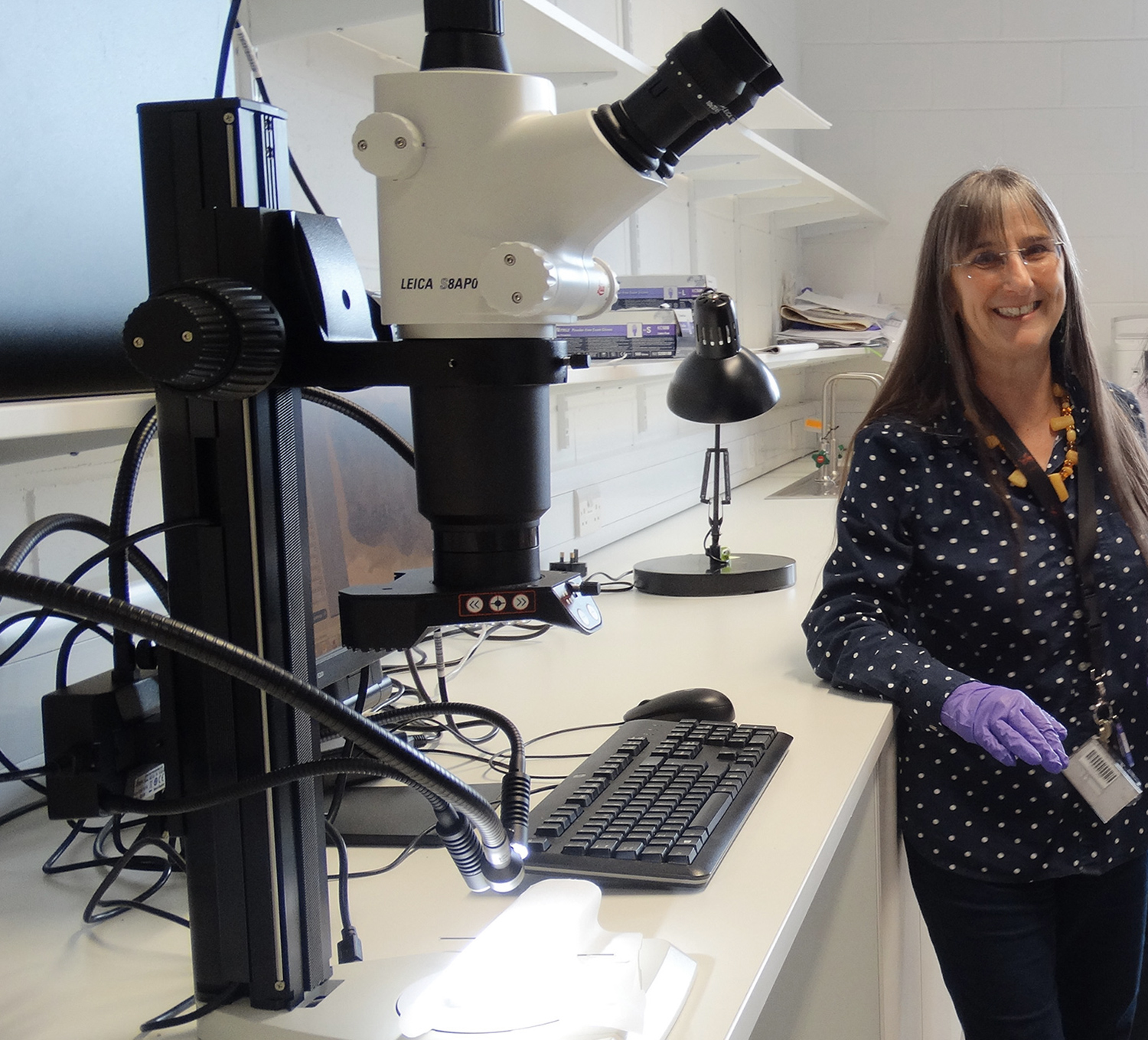

At the next stop in Scottish History, Dr Alison Sheridon, our Principal Curator of Early Prehistory, highlighted what can be learnt from looking at our past, and how it shapes our present as a country, and a nation.

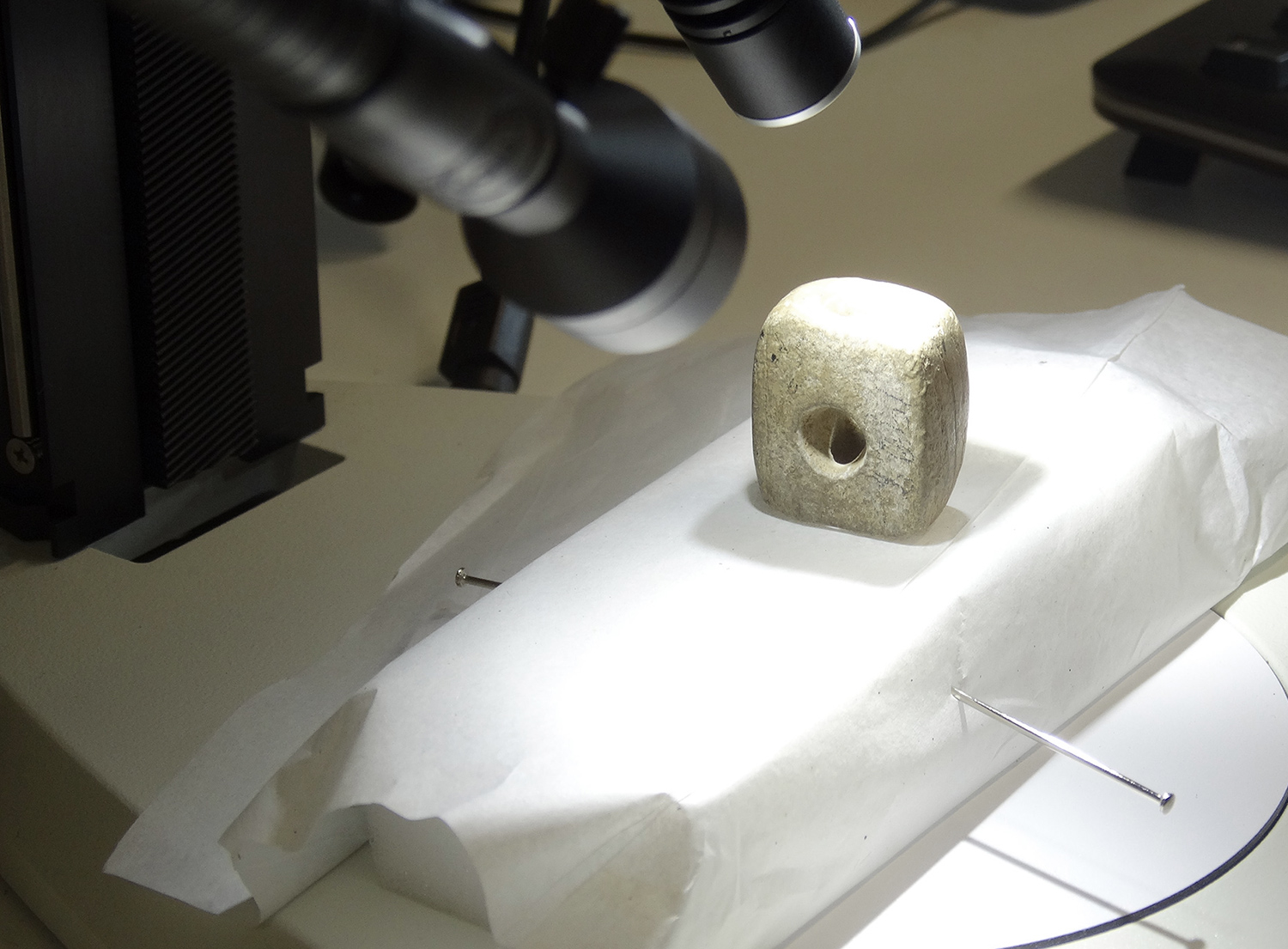

We started in the lab, where Alison had us looking through the microscope at two pieces from Skara Brae in Orkney. On first glance, this item looks relatively familiar. However, then Alison explained that it is possibly around 5,000 years old. This is when I took a second look, and you realise that there is much more to try to determine from looking closely. There are things that I would not have noticed without her expertise, so it was incredibly valuable to hear about what she sees when she looks at this item.

Then we moved back to the collection stores, to see further samples up close and hear more about new methods for storing these delicate collections.

Tour group in the Scottish History collection stores.

Tour group in the Scottish History collection stores.

The National Museums Scotland Collection Centre is home to around 12 million objects, so this tour just gave a quick insight to a small selection of the items stored behind its doors. We hope that everyone who visited on our Doors Open Day tours has left with some nice insights into the National Museums Scotland collection. However, also that it may have changed the way that people now look at the nature and elements that build up their daily environment. As, after I finished my tour, I certainly started to wonder which richer detail and stories may exist around me.

The doors are open at our four Museums all year, where we have recently opened ten new galleries at the National Museum of Scotland and there are also many brilliant treasures to discover.