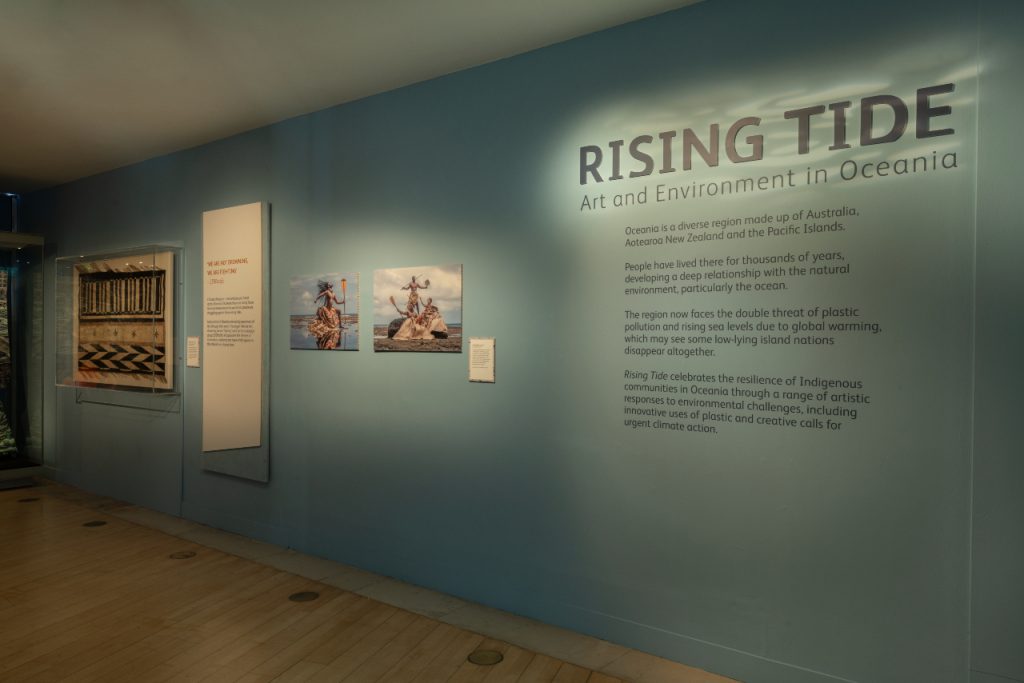

In August 2023 Rising Tide: Art and Environment in Oceania opened at the National Museum of Scotland. Here, members of the exhibition team consider how the design and build of the exhibition reflect its core themes, the Museum’s commitment to sustainability and how working with communities in the construction of exhibitions can help engage people in environmental issues.

The exhibition

Rising Tide: Art and Environment in Oceania considers how life depends on the ocean and presents various ways in which individuals within Oceania are working to protect it through the medium of artistic practice. It highlights the vulnerabilities of Oceanic countries to climate change whilst showcasing the strength and resilience of its communities.

The exhibition features several artworks that consider how Indigenous peoples in Oceania have always innovated, using materials found in their natural environment to make cultural objects. It focuses on objects made from introduced man-made materials such as plastic and glass to consider how people are using these materials as a way of cleaning up their environment, raising awareness of pollution and practicing culture.

From the start, we wanted the design and build of this exhibition to draw on the principles of Rising Tide. We wanted to have the least impact on our environment and minimise inclusion of single-use plastics.

Procurement

Firstly, we looked to source build items that would have multiple lives. For example, when displaying objects inside the cases, we bought a set of standard-sized glass shelves. This was instead of going for custom made plinths that might only last the length of the exhibition. The shelves gave the floaty ‘underwater’ effect we were after, while also being neutral enough to be used in limitless exhibitions going forward.

While seeking contractors to work with on the exhibition, we only approached local companies, to keep emissions from transporting items to the museum as low as possible. All interested companies were also assessed on their sustainability credentials, both in general and on specific actions they would take for this project. This led to us working with contractors with some very strong environmental actions. For example, the company we worked with on the exhibition films have a ‘no-fly’ policy. They are based in Glasgow and London and are committed to travelling sustainably. This meant that when they were filming Kiribati dancers in south-west England, their London crew travelled to the location by train. When they needed to film the artist George Nuku in France, they used their network of international contacts to get a local crew on board.

While building the exhibition, we were very keen to reuse as many elements as possible and had a chat with our fit-out contractor on how to make this happen. It turned out they had just taken down a wooden theatre set which was going spare. We managed to creatively source a lot of the build from this, all they needed to do was it chop it up and paint it blue. It means that most of the wooden elements in the exhibition are already on their second life.

Finally, on a housekeeping side, anything we purchase for an exhibition is recorded in a sustainability log, and the contractors we work with are required to do the same. We collate all this information at the end of the project to see if there are any lessons to be learned and to inform our approach going forward.

Sustainable design

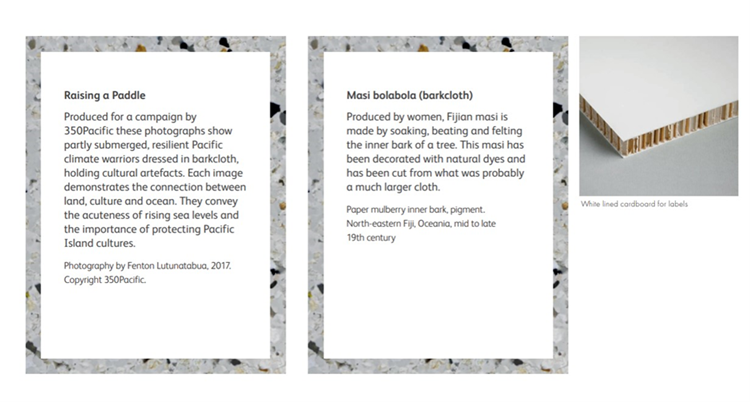

As with the procurement process, we also tried to ensure that, where possible, we used sustainable, recycled and recyclable materials for the exhibition graphics. Our main section introduction panels are made with a base of recycled wood composite, with a white-lined honeycomb recycled cardboard panel on top. We have left the edges of the cardboard exposed, so it is obvious to the visitor what it is made of. We have used this material before with great success in the 2019 Scotland’s Climate Challenge exhibition at the National Museum of Scotland, which had a similarly carbon-conscious approach.

The materials we used for the graphics have largely come from a UK-based company, who use water-free printing processes, make and use recycled materials, and offer a ‘closed loop’ system to their clients. This means they will take back products after use and recycle them where the client is unable to. The materials we are using are also very lightweight and were delivered by a carbon-neutral courier with a fleet of electric vehicles.

For the object labels, we found a 100% recycled and 100% recyclable material from a company in Buckinghamshire, UK. It comes in a range of colours and is made from waste plastic from items such as refrigerators. It is also manufactured using 100% renewable energy, is carbon neutral, and is designed to have the lowest ecological impact possible. Sounds perfect, doesn’t it?

Unfortunately, we hit a bump in the road here. We test any new materials that will be used inside show cases. While the composites passed for temporary exhibition use, Rising Tide runs for eight months, two months longer than a regular temporary exhibition. As things currently stand, the balance between sustainability and object care will always tip in favour of the latter. Instead, we made an illustration based on one of the plastic composites, which we printed onto the edges of the cardboard. So, we still got the impression of texture, just without the layers of the larger graphic panels. All in all, a satisfactory compromise. The honeycomb cardboard passed testing with flying colours.

Elsewhere in the exhibition there were some graphic elements, such as vinyl and PVC substrates that we could not avoid using. For the most part, this is the most environmentally friendly exhibition we have ever delivered. We hope it helps pave the way for more planet-conscious exhibition design in the future.

Bottled Ocean 2123

In designing the exhibition, we also wanted to make these global issues of environmental change in Oceania relevant to our local audience. We wanted to demonstrate how the issues presented in Oceania have relevance to the lives of people in Scotland. Through artworks such as George Nuku’s Bottled Ocean 2123 we hoped to be able to show visitors how these issues were relevant to them, with the intention of inspiring them to become active agents in the next chapter of environmental action.

The artwork sets out to change our relationship with plastic, treating it as a treasured resource, rather than something to be discarded. Nuku argues that the problem is not the plastic bottle itself, but our relationship with it. He argues that because we see the empty plastic bottle as a thing of waste with no further use, we become repelled by it. By transforming it into a thing of beauty, he asks us to become enchanted with it and to consider its whakapapa (genealogy). Nuku is drawing on the indebtedness of plastic to crude oil, a fossil fuel that is formed over thousands of years, to show that plastic is both the oldest – and the newest – material we have. He is reminding us that in order to create change in the future, we must pay attention to the past.

We saw an opportunity to engage children and young people from North Edinburgh in the process of working with the artist George Nuku, for the installation of Bottled Ocean 2123. Having worked in this urban and coastal area before, we knew environmental themes were being explored by local youth organisations to support resilience and build confidence. Their connection to the sea and coastal life echoed the concerns of those living in Oceania. However, we also knew the challenges faced in this area of Edinburgh, where these issues can seem less urgent than coping with the cost-of-living crisis.

To engage the young people with Bottled Ocean, we decided to focus on outdoor learning, art and creativity inspired by found and recycled materials, and chose to work with two local youth groups – Pilton Young People and Children’s Project (aged 8-11) and Granton Youth (aged 12-25), located near the Firth of Forth in Edinburgh. Our first session — a beach comb on a freezing February day to hunt for plastic debris on the Scottish coast — was a bold move, but hot chocolate and a campfire warmed the young people up, and we were excited to see what we would make with our finds.

Working with environmental artist Hannah Ayre, we turned plastic into art, echoing the themes of George’s installation to reframe it as a high-status medium. We had previously collaborated with Hannah on a similar recycled plastics project with children from Brunstane Primary school. Just as in the first project the young people then visited the National Museums Collection Centre to investigate objects made from recycled coastal material destined for Rising Tide. Here, they witnessed first-hand the plastic debris found inside a whale washed up on a Scottish beach.

For Bottled Ocean, community is key to how the installation is produced, with Nuku bringing together local teams of volunteers to help produce and construct the installation.

In July 2023 during the installation phase, George visited the youth groups’ location to work together with them to create pieces for the artwork – turning plastic bottles into glittering jellyfish, which a team of volunteers then helped George to install. We also ran family drop-in workshops in the Learning Centre at the National Museum of Scotland to make more jellyfish. We then worked with a team of adult volunteers which included students from Edinburgh College of Art and members of The Welcoming Association, an Edinburgh-based charity that supports refugees, asylum seekers and migrants, to build the installation. Overall, we worked with around 400 individuals to realise the installation which took 16 days to install.

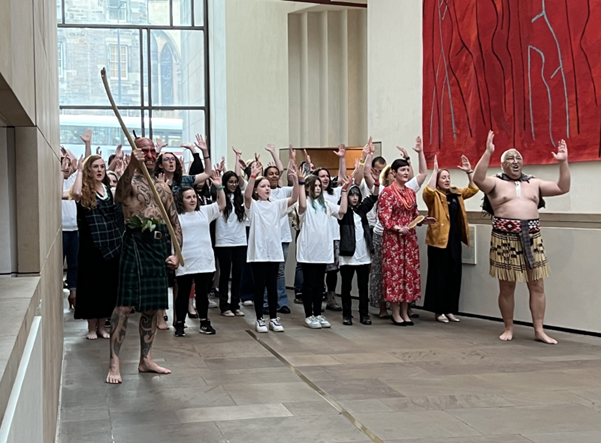

The opening

For the opening ceremony in September 2023, young people and adult volunteers were invited to the National Museum of Scotland to help George deliver a welcome blessing for the exhibition. Part of this welcoming involved performing a Māori haka (a ceremonial dance) to bless the space and to welcome people into that space. The children, while at first nervous to perform in public, eventually warmed up to the idea of being part of something so significant, and excitedly discussed bringing family and friends back to Rising Tide.

The reason that George involves so many people in the production of his installations is that he believes that it is only through the act of making and participating can we change people’s mindset. In addition to the transformation of plastic waste into a beautiful artwork, each volunteer is also transformed themselves. They become campaigners for climate justice who are able to communicate the environmental message of the artwork to audiences in their local environment and make the issue of environmental change in Oceania, relatable to audiences across Scotland.

We hope that the message of valuing discarded materials and how local choices can affect the lives of others across the world, help these young people understand the positive actions they can take to combat the climate crisis and connect them to a shared global goal.

You can learn more about National Museums Scotland’s wider approach and responses to sustainability, climate and biodiversity loss by reading our vision for sustainable development.