A Stirling engine is powered by hot air rather than steam. Now 200 years old, its revolutionary technology has become even more relevant today.

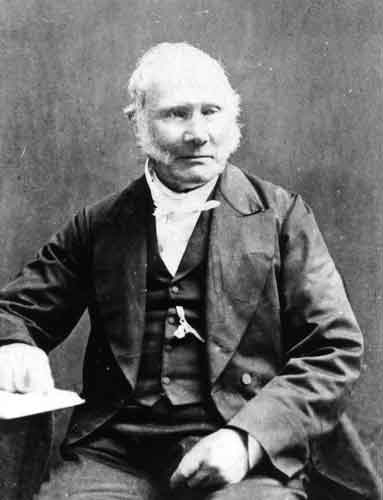

Reverend Robert Stirling was a Church of Scotland Minister with a strong interest in engineering. Robert worked closely with his brother to develop and refine the hot air engine technology which would not be coined the ‘Stirling’ engine until around 100 years after its development. Stirling’s idea was prompted by the need to create a safer alternative to the steam engine. During the 19th century, boiler explosions at high pressure were a frequent occurrence and many enginemen and bystanders were killed or injured. The Stirling technology was also considerably cleaner to operate, leading to further improvements in working conditions.

Some work had been done around the idea of hot air engines prior to Robert Stirling, but his key innovation was what he called an ‘economiser’ which he patented with an engine incorporating it in September 1816. Now known as a regenerator, this technology was designed to reuse wasted heat from the engine. This improved efficiency as heat could be stored and reused, reducing the amount of fuel required for operation.

Dr Ralph Lorenz tells us how NASA has used the Stirling engine technology in space exploration.

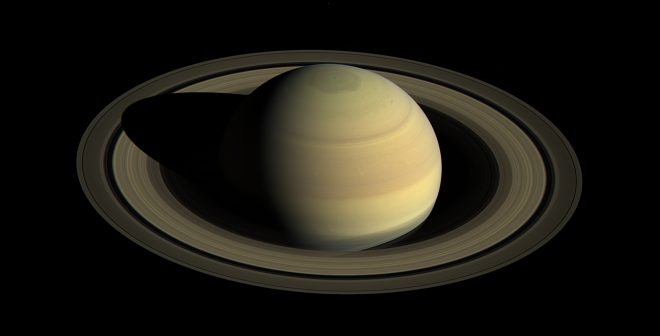

Most satellites use solar panels for electrical power. However, these are impractical for spacecraft exploring the outer solar system: because Saturn is ten times further from the sun than the Earth, it gets only a hundredth as much sunlight.

The heat from radioactive decay of elements like Plutonium can be used to generate steady power independent of the sun, and NASA has used thermoelectric generators powered this way for many of its deep-space missions, including Cassini and New Horizons. Thermoelectric generators are reliable, with no moving parts, but are very inefficient, converting only about 5% of the heat into electricity.

NASA has been exploring better power sources, and has been developing a generator, based around a Stirling engine, for space use. This would use a fourth as much of the precious Plutonium to generate as much power as a thermoelectric system would need.

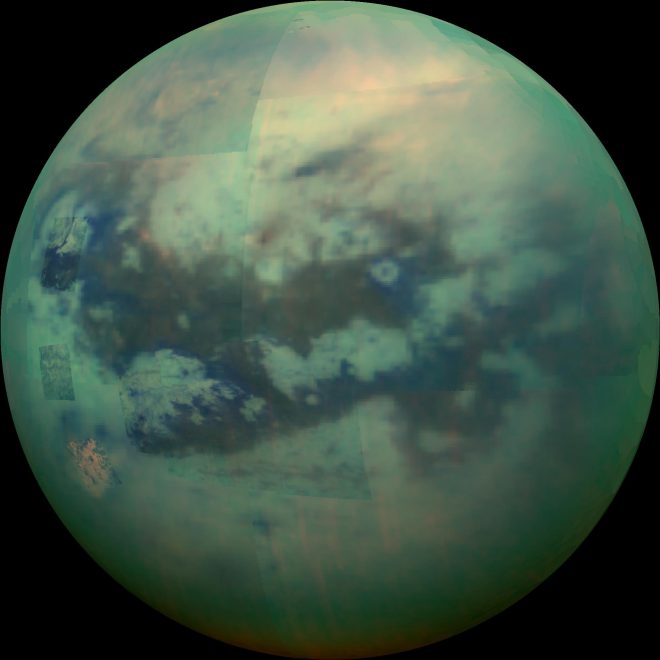

I worked for several years on a proposal (TiME – the Titan Mare Explorer) to fly a capsule to splash down in and float around on Ligeia Mare, one of the frigid hydrocarbon seas of Saturn’s moon Titan. Although the sea is a vast reservoir of liquid natural gas, there is no oxygen on Titan to burn it in, and so this capsule would need a source of heat and power.

Two of NASA’s Advanced Stirling Radioisotope Generators (ASRGs) were to give it about 200W of electricity. Unfortunately, even though a Stirling generator has only one moving part, it is very challenging to make such a system work reliably in space for a dozen years or more without adjustment or repair, and in 2012 NASA decided it could not take the TiME concept forward. Nonetheless, the Stirling engine remains one of the most promising approaches for efficient spacecraft power, and tiny versions of the system are ‘run backwards’ to cool ultra-sensitive heat-sensing instruments on several satellites.