This summer a team from the Science and Technology and Collections Services departments re-located the historical chemicals collection.

We moved from a rather cramped and gloomy store in one of the older storage buildings at the National Museums Collections Centre, into a more spacious and brightly lit storeroom nearby, with greatly improved environmental conditions and storage facilities. We photographed everything and then re-packed it into conservation-grade boxes; this was an excellent opportunity to audit the collection and to gain an overview of its historical importance.

The collection consists of numerous samples of metals, ores, crystals, liquids and solvents in historic glass containers in a variety of shapes, with hand-written, typed or printed labels which reflect the various sources for collections, and the changing identity of the Museum since its foundation.

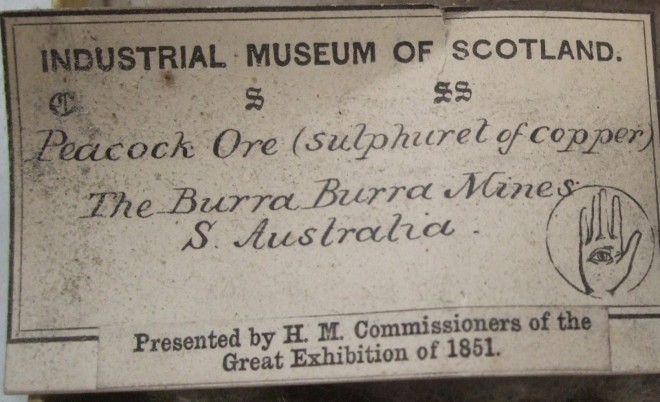

Some of the oldest samples were ‘Presented by H.M. Commissioners of the Great Exhibition of 1851’, as stated on labels from the Industrial Museum of Scotland, founded in 1854. Many of these labels also have the mysterious symbol, or crest, designed for the museum by Professor George Wilson (1818-1859), Regius Professor of Technology at the University of Edinburgh and the first Director of the Industrial Museum.

In 1857 he wrote that Chemistry could be represented by an active, inquisitive and scrutinising hand, and astronomy by an eye; “The symbol of industrial science is a hand with an eye in the palm and the fingers free”[i] In 1858 he explained this further: “an open hand, as the symbol of the transforming forces which change those materials; and in the palm of that hand an eye, selecting the materials which shall be transformed.”[ii] These samples fit perfectly with the founding ethos of the Industrial Museum, as they illustrate all stages of industrial processes, including mining, dyeing, mineral and fuel extraction.

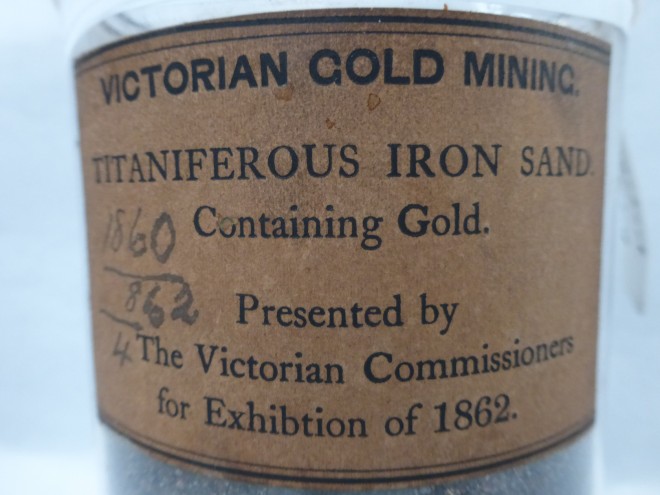

Another source for samples was the International Exhibition of 1862, or the Great London Exposition, sponsored by the Society for the encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce (which later becamse the Royals Society of Arts). A jar of Titaniferous Iron Sand containing gold was ‘Presented by The Victorian Commissioners for Exhibition of 1862′.

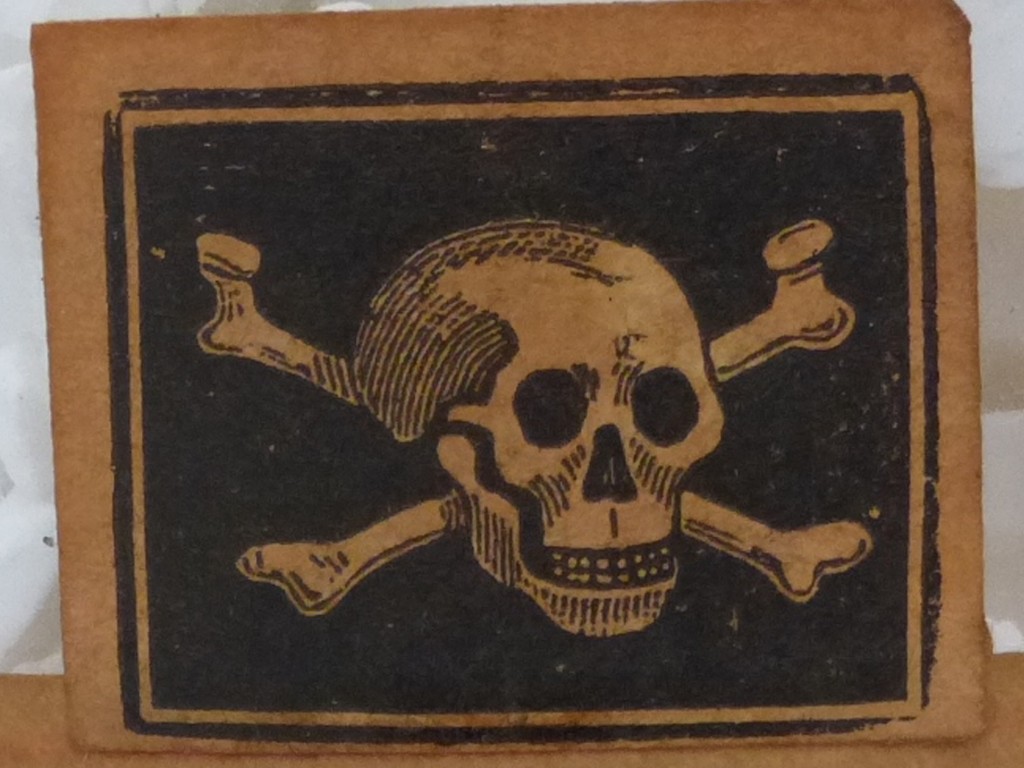

In 1864, the Industrial Museum of Scotland was renamed the Edinburgh Museum of Science and Art; as can be seen from accession labels from this period. Later labels are less aesthetic, typed by typewriter, computer, and occasionally scrawled in ballpoint pen or crayon. However, health and safety was still a concern at the turn of the century, as indicated by a rather lovely skull and crossbones label on a bottle of bottle of arsenious acid from 1903.

Many of the samples had travelled for many miles across land and oceans, conjuring romantic images of mountains and deserts; or perhaps miners working long, dark and dangerous shifts deep underground, far from the wealthy drawing rooms of Victorian Britain. Samples labelled with exotic-sounding origins include:

- A sample of mixed copper ore from the Burra Burra mines, South Australia.

- Native Sulphur. This specimen is from Ollague in the volcanic region of the Andes, Chili [sic], where it is worked at a height of 19,000 feet. Presented by Mr. C.R. Drummond, Antofagasta, Chili, S. America.

- One of six specimens illustrating gold sand from the Kazansk Diggings, Government of Perm, Russia – a sample of diorite bed.

- Orange and black atacamite (hydrated oxychloride of copper) from Santa Rosa Mine, Socopilla, Bolivia. Presented by His Excellency Sir Ronald F. Thomson, Teheran.

- Chrysocolla (silicate of copper) Tamaya, Coquimbo, Chile.

Elsewhere the chemicals themselves have poetic names and descriptions, such as:

- Auriferous quartz – of or containing gold;

- Argentiferous – of or containing silver;

- Titaniferous – of or containing titanium;

- Plumbous – of or containing bivalent lead;

- Plumbago – another name for graphite.

One interesting collection was that donated by Messrs Nobel’s Explosives Co. Ltd, all in beautiful glass vials with hand-cut stoppers, luckily including “Specimen illustrating explosives – a sample of dummy nitroglycerin in a glass bottle”.

Finally, certain groups of chemicals were beautiful and fascinating simply in the variety of colours in similar metallic or chemical groups, and also in their complex crystalline structure; see also blog by Dr Tacye Phillipson.

[i] Edinburgh New Philosophical Journal, 1857 (Vol. 5) p.84.

[ii] Jesse Aitken Wilson, Memoir of George Wilson, Edmonston and Douglas, 1860 p.501.