Part 1 of a series documenting the conservation of silver artefacts for Scotland’s Early Silver exhibition.

It has been a few weeks now since the Scotland’s Early Silver Exhibition opened its doors and it feels almost unreal that our Artefact Conservation team managed to work our way through nearly 900 objects and fragments for display. From basic conservation cleaning and removing tarnish to the complex reconstruction of fragmented vessels – we managed to do it all for Scotland’s Early Silver.

It is really hard sometimes to appreciate the amount of conservation work and the number of different specialist teams involved in National Museums Scotland exhibition projects like this one. We would never make it happen without the close working relationships and invaluable expertise of our curators, assistant curators, exhibition officers, designers and illustrators, photographers, mount makers and tech teams.

But let’s focus on the conservation work for now. We often consider our work mundane and boring as it involves very long hours staring into the microscope to slowly clean the surface of objects which might fall apart…

But as it turns out, the most interesting things in conservation are very often are the little details which people don’t usually notice.

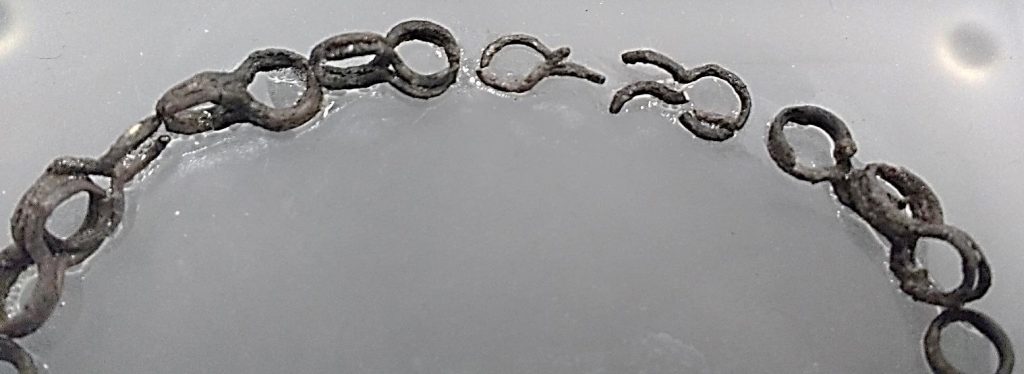

This little silver necklace from the Roman site at Newstead, late 1st or 2nd century AD is now on display looking all pretty and shiny, but this wasn’t always the case.

Before conservation

As you can see from Fig.2 – the object was previously stuck directly onto a Perspex mount.

At a first glance doesn’t look that bad, right? But if you look closely you would first notice the lumpy blobs of adhesive covering the gentle fragile chain. Then you would see that all the chain loops have missing links and there are single broken fragments randomly stuck to the mount. The arrangement of the object was deceivingly suggesting that it is a bracelet when it is actually a necklace.

So with the advice of the curator, a decision was made to dismantle the object from the old “mounting” and to conserve and re-mount it in a more sympathetic way.

During conservation

After dismantling the object from the old mount and removing all the excess old adhesive it became apparent that some of the chain loops were loose and some of the detached fragments were not in their right places.

The conservation work included re-attaching the loose chain loops and locating the correct places for the randomly floating fragments. We used a combination of glass tape and mini clamps to hold the fragments together while the adhesive was drying.

It is amazing how important is to carry out all this work looking under a microscope, as we managed to match most of the loose fragments to a set of chain loops.

All surfaces of this fragile object were heavily tarnished and covered with accumulated dust which made it hard to assess how much of the metal was still there. After carefully cleaning mechanically the surfaces using small dental tools and fine brushes, and reducing the tarnish using solvents it became apparent that most of the metal was in a fairly stable condition.

Some of the re-constructed chain loops had areas with too little surviving metal to allow them to be re-mounted. The exhibition design was for the conserved object to be pinned onto an angled board. Our conservation solution was to make a replacement loop, using thin strips of Japanese tissue. These were coated with acrylic resin and then bonded to the missing areas, creating a loop. The Japanese tissue paper loop was then coloured with acrylic paint to blend with the original.

After the conservation of this beautiful object was completed we had to think of a mounting solution. None of the chain loops was linked to each other and the object had to look like an actual necklace when displayed…

What shall we do?

Luckily in conservation, we get creative inspiration from almost everywhere – it could be our own kitchen or from a specialist discipline like medicine.

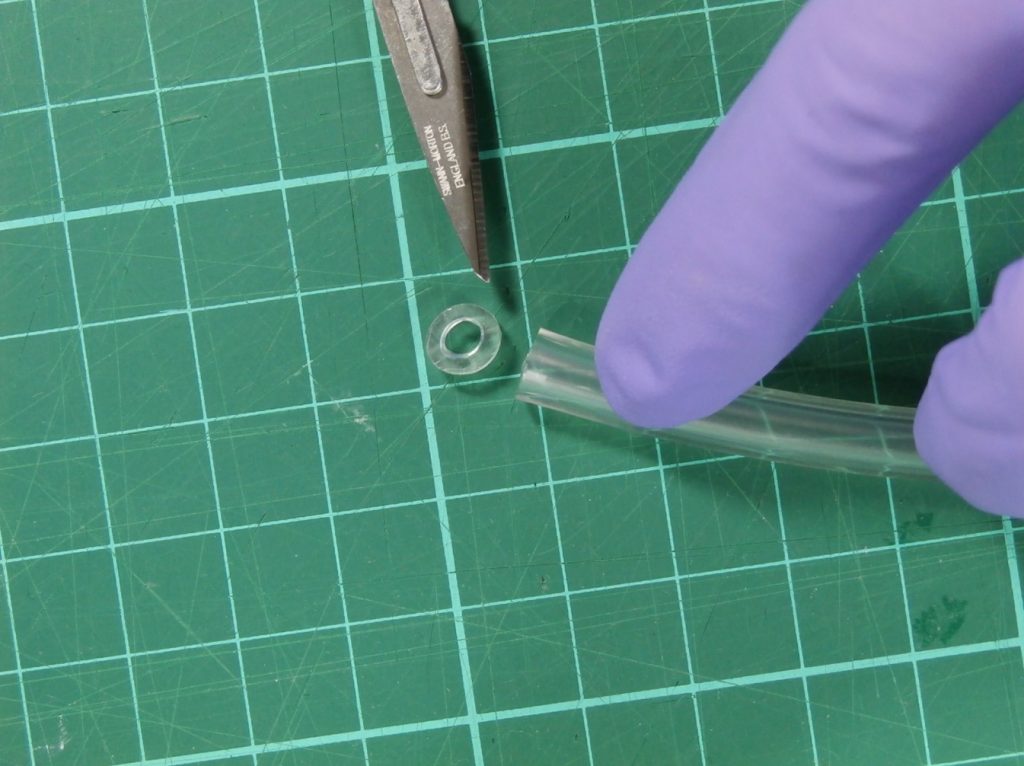

In this instance we used surgical tubing to cut out small loops, similar in size to the necklace links to create replacement loops – an ethical and non-invasive solution for mounting.

Linking the chain in this way made it stable for handling and mounting, easy to pack and transport and held practically all the loose fragments together.

Conserving this object also allowed conservators and curators to view and examine the other side of the object for the first time since it first arrived in the museum.

After conservation

Acknowledgements

Special Thanks to all the teams who made the Conservation work for the Scotland’s Early Silver exhibition so enjoyable!

Curatorial Department

Alice Blackwell – Glenmorangie Research Fellow, Scottish History & Archaeology

Fraser Hunter – Principal Curator, Prehistory & Roman Archaeology

Jim Wilson – Assistant Curator, Prehistory & Roman Archaeology

Craig Angus – Assistant Curator, Medieval Archaeology & History

Exhibitions

Hannah Boddy – Lead Exhibition Officer

Collections care: Conservation

Jane Clark – Head of Artefact Conservation

Charles Stable – Artefact Conservator

Diana de Bellaigue – Artefact Conservator

Lydia Messerschmidt – Assistant Artefact Conservator

Julia Tauber – Assistant Conservator Science & Technology

Tatiana Marasco – Preventative Conservator

Amreet Kular – Artefact Conservation Intern

Collections care: Science

Lore Troalen – Analytical Scientist

Photography

Neil McLean – Lead Photographer, Collections Information

Mary Freeman – Photographer, Collections Information

Design

Esther Titley – Designer

Kimberly Baxter – Designer

External contractors

Alan R Braby – Archaeological Illustrator @brabyshep

Richard West – Mount maker @lightlywest

The Glenmorangie Research Project aims to extend our understanding of Scotland’s Early Medieval past and was established in 2008 following a partnership between National Museums Scotland and The Glenmorangie Company. The current phase of research, Scotland’s Earliest Silver: power, prestige and politics will look at the biography of this precious metal as it was used and reused in Early Medieval Scotland.

Scotland’s Early Silver exhibition is on at the National Museum of Scotland until 25 February 2018 and follows three years of research supported by The Glenmorangie Company.