Tartan’s bold and sometimes scandalous history is retold in 19th century pattern books and trade catalogues at the National Museums Scotland Library that form part of our Special Collections. Assistant Librarian Jennifer Higgins puts the spotlight on several of these books to better understand how the mass adoption of Highland Dress was inspired, and sometimes critiqued, by contemporary literature.

Both libraries at the National Museum of Scotland and at the National War Museum carry publications documenting tartan’s contradictory nature as a pattern that is simultaneously traditional and radical, local and global, authentic and counterfeit. All first editions of the books profiled here were published in the mid-19th century when Scottish Romanticism dominated literature and the arts. This is largely thanks to writers and artists such as Sir Walter Scott (1771–1832) and Alexander Nasmyth (1758-1840) who toured the Highlands and produced works that glamourised selective aspects of Gaelic traditions and culture.

In 1822, King George IV visited Edinburgh wearing a bright Royal Stewart kilt styled with a pair of much-maligned pink tights. The enormous pageant organised by Sir Walter Scott for the occasion, specified that those attending the Highland Ball at the Assembly Rooms should adorn Highland dress. That moment is often viewed as a flashpoint when the kilt was cemented as Scotland’s national dress and as feeding into the craze for categorising commercial tartans by clan.

Tartan, of course, had been around long before the 19th century. Yet, following the ill-fated 1745-46 Jacobite Rising (that led to Highland Dress and certain items of tartan attire outlawed by an Act of Prohibition). George IV’s visit marked a major public revival for plaid, securing its wider appeal in settings and social contexts beyond the Highlands and Gaeldom.

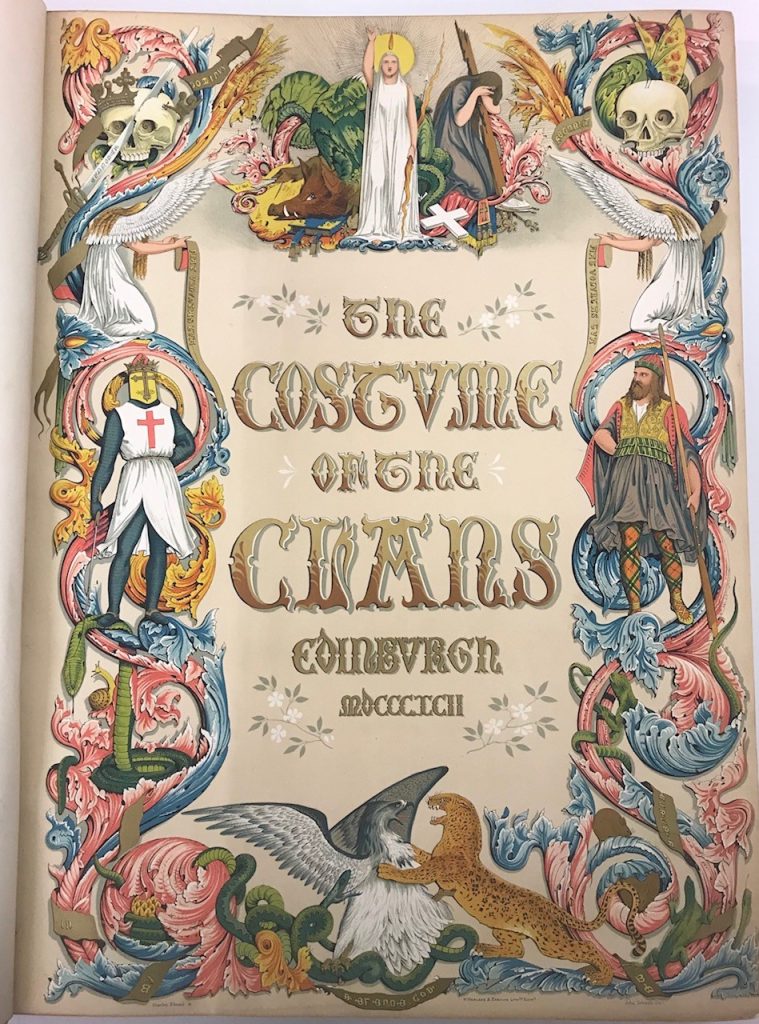

Take, for example, The Costume of the Clans by brothers John Sobieski Stolberg Stuart and Charles Edward Stuart. A first edition of this elephant folio (to describe a printed volume about 23 inches in height) from 1845 is one of the objects selected for display at the current Tartan exhibition at the V&A Dundee, running until 14 January 2024. The folio is sumptuously bound in scarlet-red leather and dedicated to the King of Bavaria with an address in Scottish Gaelic and in English to the ‘beloved people,’ the Highlanders.

The 1892 edition has been embellished to feature two lavish coloured plates. One of these plates is the title page, decorated in gold-leaf, which depicts King Canute parting the waves to reveal animals, serpents, and skulls in an outrageously flamboyant battle between a knight of St George and a Gaelic Highlander. All of this is opposite the frontispiece depicting John Sobieski in full garb and sword – just in case the authors’ pro-Jacobite political allegiances were not obvious enough.

The publication was intended to tug at the heartstrings of Scottish nationalists, proposing that only Highlanders authentically wore clan tartan, and that the mass popularity of tartan among non-Highlanders was nothing more than sartorial fancy dress. The Sobieski-Stuarts claimed to be the legitimate grandsons of Prince Charles Edward Stuart, popularly known as ‘Bonnie Prince Charlie’. In fact, they were John Carter Allen (1795–1872), and Charles Manning Allen (1799–1880), born in Wales to a Royal Navy family.

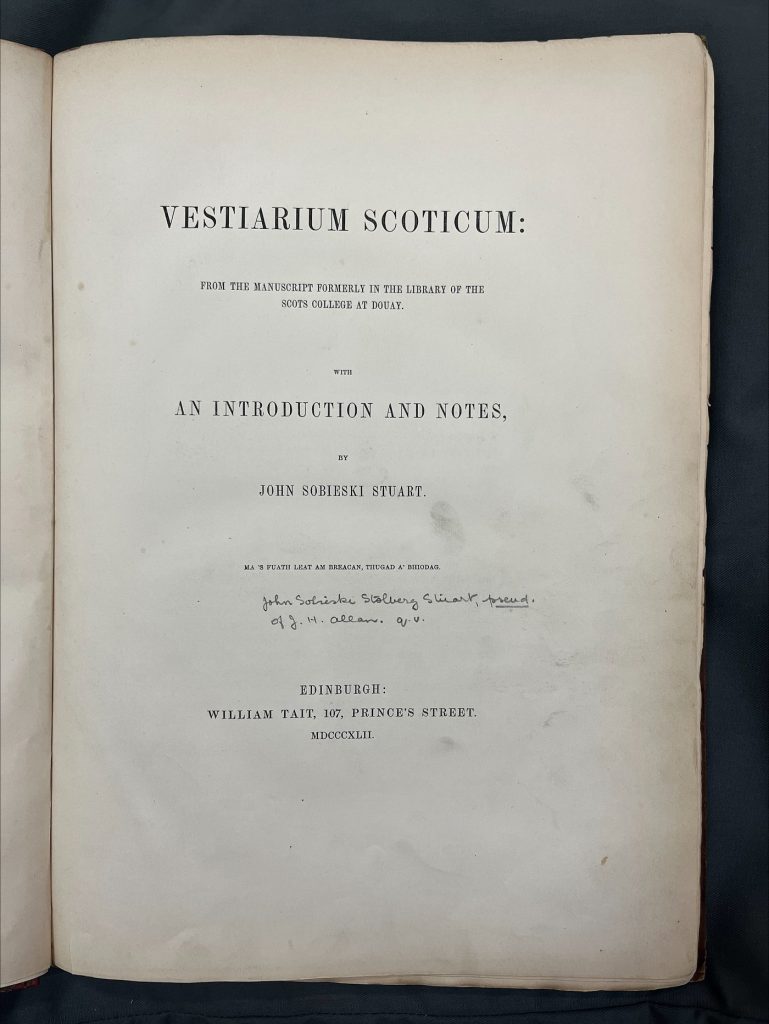

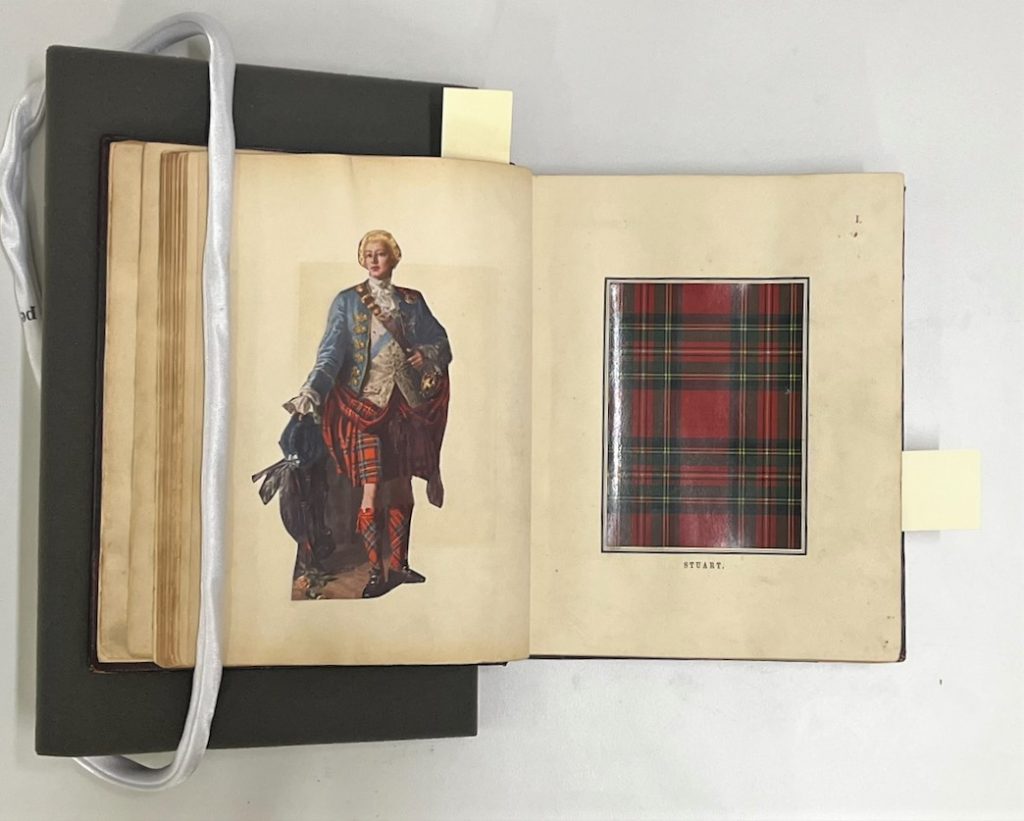

The great tartan sensation at the time of the book’s publication long outlasted fervent criticism of the book’s legitimacy in which the brothers controversially claimed the tartan illustrations were based on bona fide historical research. It followed hot on the Ghillie Brogue heels of their earlier publication, Vestiarium Scoticum (1842), allegedly based on an original (and top-secret) Jacobite manuscript of Highland and Lowland tartans. The self-styled influencers of their day, the brothers were subsequently referenced by tartan scholars and manufacturers, forever weaving together tartan heritage and historically dubious narratives.

The Sobieski-Stuarts are connected to the next rare book in the library’s collection, Authenticated tartans of the clans and families of Scotland (1850). This title was published by a second set of brothers, William and Andrew Smith. The Smiths were makers of Scottish snuffboxes in the village of Mauchline, Ayrshire, at the heart of its flourishing woodware industry. ‘Mauchline ware’ describes handmade souvenir pieces decorated with pastoral scenes of Scottish life. In its infancy, tartans were hand-painted onto the wood or using paper. The fine craftmanship (and very steady hand) this required, limited the range of tartans that could be reproduced. The commercial opportunity to print tartans was seized on by the brothers who, using a chromo-plate printing process, were able to machine-make tartan!

Never ones to miss a trick, when rumours of the Smiths’ innovation reached the Sobieski-Stuarts, they capitalised on the Smiths’ chromolithographic plate technique to produce Vestiarium Scoticum. That Authenticated tartans of the Clans of families of Scotland has an ‘introductory essay on the “Scottish Gael” by a member of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland,’ which could well explain the reason for a copy of this book finding its way from Mauchline to Edinburgh where the Society is based. The Library at the National Museum of Scotland holds the Society’s archive and historic book collection.

Completing our tartan ‘sett’ is Gaelic Gatherings, a collaboration between the author James Logan and Scottish artist R.R. McIan and sequel to the pair’s popular compendium of costume and arms, The Clans of the Scottish Highlands. This book is drawn from our collections at the National War Museum Library at Edinburgh Castle, open to the public by appointment. In the same way as the Sobieskis’ Costume of the Clans before it, the book played a marketing role for Highland customs and dress through its sentimental illustrations and prose. The library has both the 1848 edition and this tartan-cloth bound edition replete with a gold stamp of Royal Arms of Scotland on the front board and gilt-edging. It is reprinted from the original 1845 edition, and published in 1900, a year before the death of Queen Victoria.

Regarding royalty and tartan, the National War Museum Library features an impressive section on military uniform and weaponry. Scottish regiments took tartan on tour around the world, marketing it to global cultures with similar clan systems and fabric manufacturing processes. In no case is this more apparent than with the Royal Highland clans, in whom Victoria maintained a close interest and helped to fan the Scottish Romantic revival.

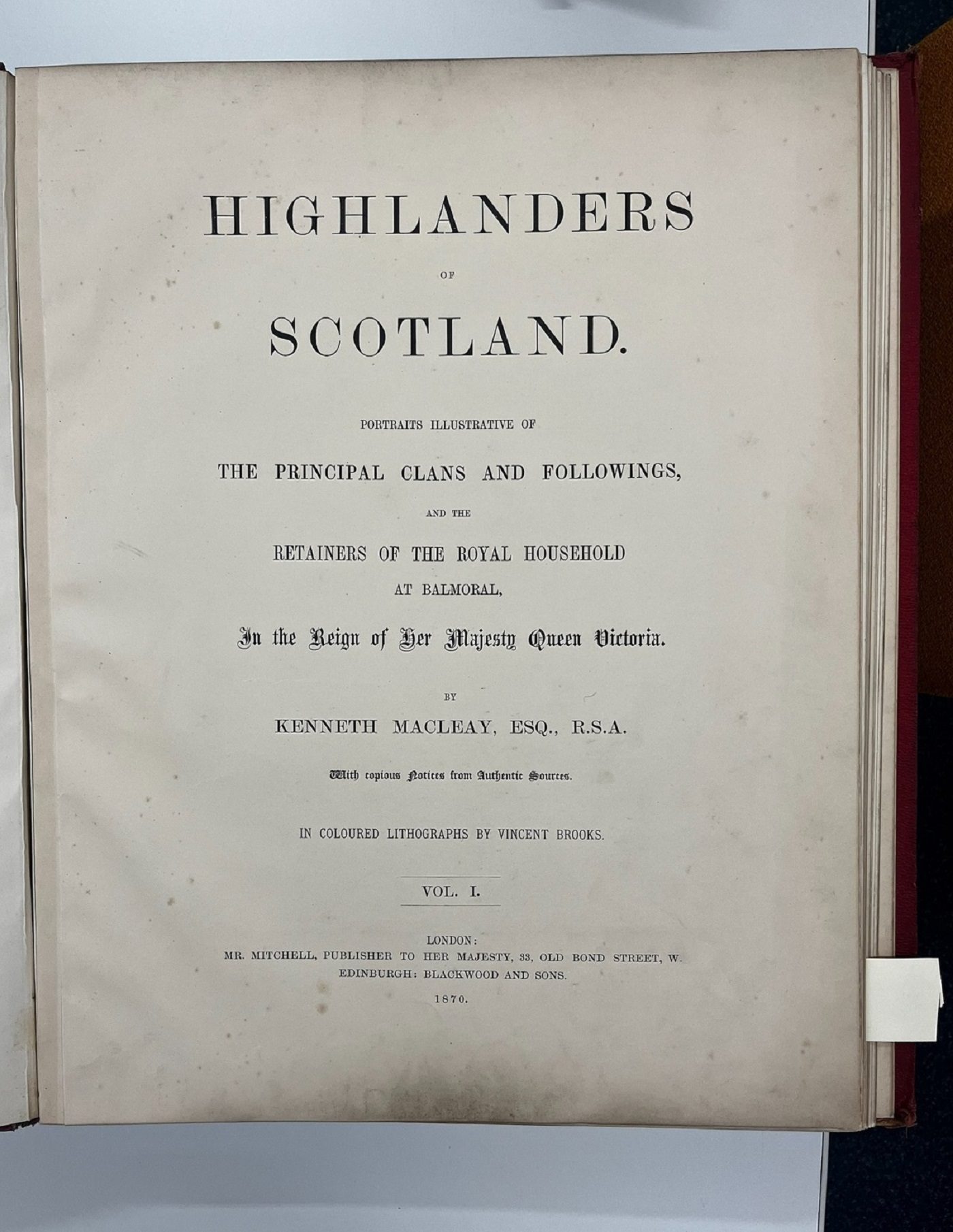

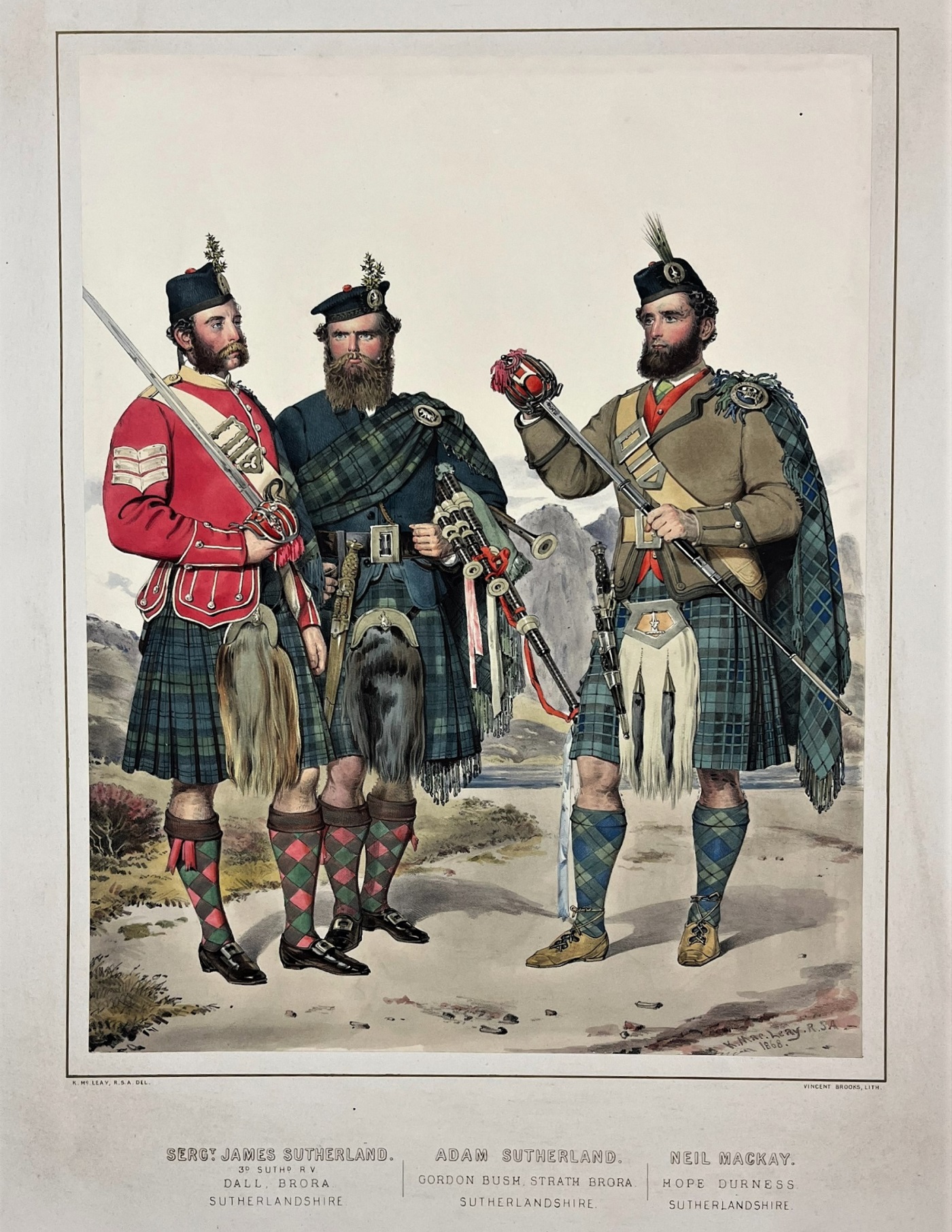

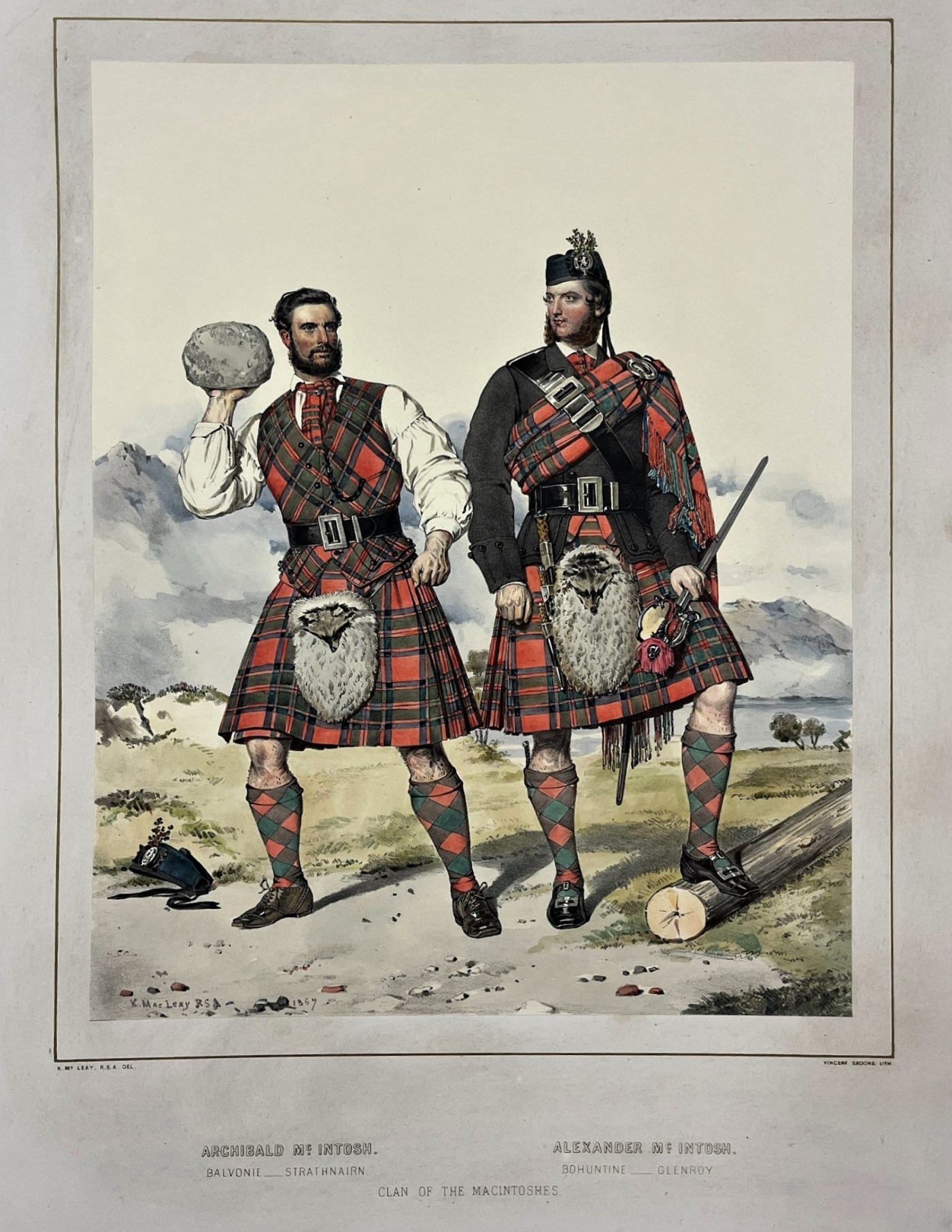

At Balmoral, the monarch commissioned Scottish artist and proud Highlander Kenneth MacLeay to produce watercolour portraits of her favourite royal attendants, dressed in their finest regalia. The project quickly evolved to include portraits of the principal clans, with the result being a handsomely illustrated two-volume folio, Highlanders of Scotland: portraits illustrative of the principal clans and followings, and the retainers of the Royal Household at Balmoral, in the Reign of Her Majesty Queen Victoria (1870). While serving as an extravagant tribute to Victoria, MacLeay’s work is another example in the history of tartan publishing to have sustained tartan’s popularity in the 200 years since the 1822 Scottish pageant.

We welcome visitors to the National Museums Scotland Library at Chambers Street and at the National War Museum at Edinburgh Castle, whatever the nature of your research. To make an appointment to view any of our fantastic tartan titles or items on the library catalogue, email Library@nms.ac.uk.

What does the present and future of tartan look like? Watch videos with modern tartan makers, take garments for a 360° spin, and much more with our Tartan Today pages.