It’s a warm June 2019 night in Sutherland. A bunch of historians from the Highlands and Islands’ own university are gathering, along with over a hundred others, outside a small community hall. They’re there to watch a sold-out show featuring a band of five leading women musicians, all of this supported by an organisation with a mission of enabling the region’s people, whatever their age, to learn an instrument and engage with Gaelic culture.

Would Lauren MacColl’s project, The Seer, a body of music and tour inspired by historical memory and mythology dating back to the 17th century, have been possible in 1973, the year that Runrig formed? Who would have predicted then either the advent of the Fèis movement, which has buoyed Highland music so much, or, indeed, of the region having its own Dornoch-based Centre for History, a key part of a University of the Highlands and Islands?

As historians, we write often about people and land. Over the last few years, the work of the Centre for History’s staff has influenced the drafting of the 2016 Land Reform (Scotland) Act, helped open up national debates around the rewilding and re-populating of the Highlands, and inspired a ‘heritage from below’ approach to the theme.

This kind of history writing has interacted with the arts and with music. As our Centre’s founder and former director, Professor James (Jim) Hunter, expressed it, in 2007, in seeking to understand issues around land or regeneration, it had become crucial not just to research and write, but to consider creative life:

‘to make people feel good about themselves and their surroundings; to show that the Highlands and Islands, once dismissed as hopelessly impoverished, are actually rich in music, architecture, literature, archaeology and much else’.

James Hunter, ‘History: Its Key Place in the Future of the Highlands and Islands’, Northern Scotland, (27), 2007, pp. 8- 9

This article and quote came back to me when I was driving to work in Dornoch one day in the summer of 2018, and heard on the radio Donnie Munro – Runrig’s frontperson for their first twenty-four years – cite Jim’s work as a major influence. Thankfully, I didn’t crash my car but decided to pursue the idea of an event to explore that interaction. Momentum built.

By email, Calum MacDonald – along with his brother Rory, the band’s major songwriter throughout their career – confirmed that Jim’s writing has been ‘a source of great inspiration for myself and my colleagues and for many of our generation.’

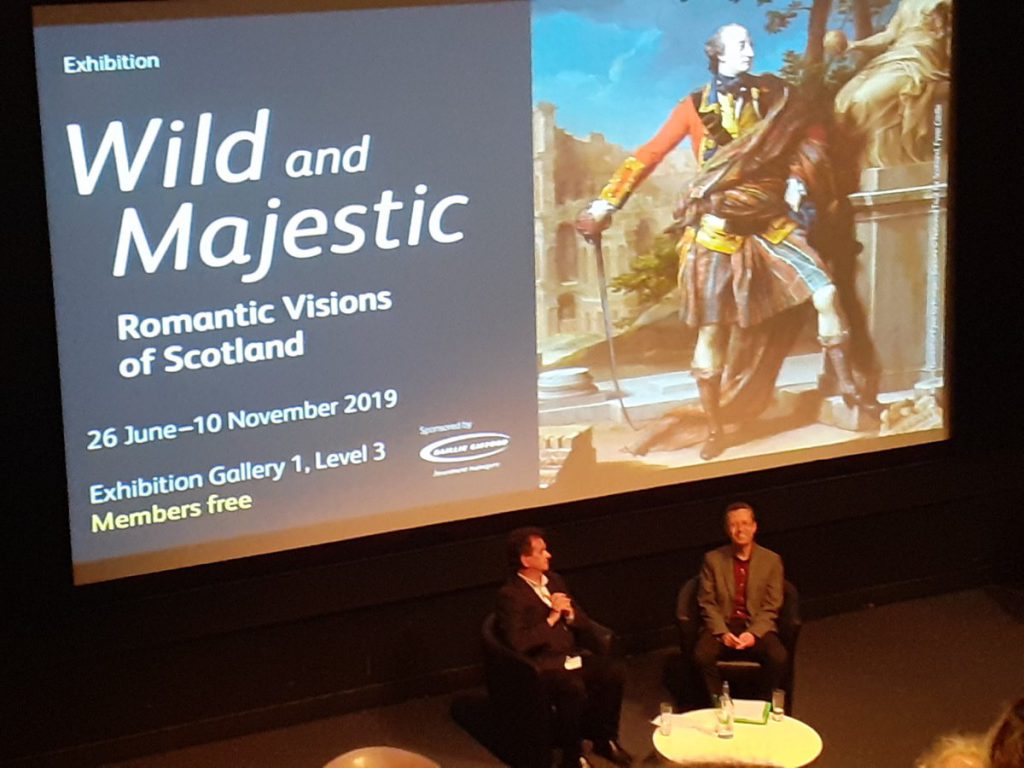

The team at National Museums Scotland took the lead impressively, and, so it was that on 4 July 2019, I was lucky enough to be conversing with Donnie Munro in the National Museum of Scotland, in front of a sell-out crowd.

The quote from Jim above inspired enthusiastic reactions from the audience too. As one, younger attendee put it: ‘I feel that the view that the Highlands are “hopelessly impoverished” is changing and I think there is definitely more importance being given to the culture and history of the Highlands and Islands in a Scottish wide context’.

A section of the evening’s discussion focused on excerpts from five songs that fascinate me – as not all of them well-known – drawn from the period of his involvement in the band.

‘Fichead Bliadhna – Na Luing Air Seoladh‘, from 1979, kicked things off. Donnie outlined how a lack of schooling in their Gaelic past or language, and then the growing radicalism of visual art, theatre, literature, newspapers, and history, had fuelled the fire. From justified anger can, eventually, come renewal.

My second choice was the title track from the 1981 album, Recovery, the song, and the album that, most explicitly, drew on Jim’s social history of the region ‘after the clans, after the clearings’.

‘Flower of the West’ from 1991 comprises an intensely emotional evocation of a micro-historical landscape. We heard a fragment of Calum and Rory’s North Uist psychogeography set to music, this leading to a discussion about the ‘wild and majestic’ theme of the exhibition (Donnie outlined that, for him, Highland dress was the ‘baggy jeans and wellies’ of crofting). There followed reflections on Runrig’s own psalm- and Neil Gunn-influenced response to conceptions of the region’s character and spirituality.

Regarding the next choice, ‘Move a Mountain’, from 1993, I have always been intrigued: not many bands would link the attempted Harris ‘superquarry’ with post-Chernobyl eco-consciousness and the 1992 Los Angeles riots, in a single song.

Via ‘The Mighty Atlantic’ from 1995, I was keen to talk about emigration, boats and fishing, intrinsic themes to Runrig, of course, the lyrics to this one conveying hope as well as traumatised exile in the sea crossing.

Donnie was not the band’s songwriter, and the MacDonald brothers have gone on to write further stunning songs, with Runrig releasing several important albums without him down to 2018, all inspired by an approach to music that, as Calum’s comments make clear, the work of Highland historians still informs. Given Donnie’s major role in musical, political and public life today too, though, it was heartening that he felt we had provided a ‘gracious recognition of Runrig’s role in the wider regenerative agenda’.

Artists, museum curators and historians know better today than they did in 1973 how creative responses to land can re-present historical themes, the relevance of which lie in the way they are remembered as well as in the horrific, majestic or contested facts of their happening. I headed back north inspired by the ongoing power of our Centre’s work – despite the challenging passages we know will lie ahead – to contribute to the land reform debate.

More broadly, is it perhaps the case that recent years have seen the region pitching less frequently in a treacherous ocean but with its eyes on more sheltered kyles, sounds and firths? I certainly believe that the Highlands and Islands is readier than it was in 1973 for new, ambitious crossings, in the knowledge that, in Runrig’s music and in its best recent history-writing and curation, ‘there’s a lighthouse, shining in the dark’.

‘Runrig and Highland History’ was part of a programme of events accompanying the exhibition Wild and Majestic: Romantic Visions of Scotland, which runs at the National Museum of Scotland until 10 November 2019.

Find out more and book tickets at www.nms.ac.uk/wildandmajestic.

For a detailed analysis by the MacDonald brothers of their lyrics to these five songs, and over a hundred others, see Calum MacDonald and Rory MacDonald, Flower of the West: The Runrig Songbook (Aberdeen, 2000), pp. 102-3, 106-7, 116-7, 184-5, 252-3.

Header image: Colonel William Gordon of Fyvie by Pompeo Battoni © National Trust for Scotland, Fyvie Castle.