What does replacement mean to you? Have you replaced part of a much-loved object? Global Arts, Cultures & Design Administrator Clare Hyatt interrogates the act of replacing parts of objects and explores how that allows us to better understand being human.

The concept and act of ‘replacement’ has many different iterations. In repairing or replacing what is broken or worn out, the life and use of an object can be renewed. Extending the life of an object means we generate less overall waste and reduce our environmental impact as a result. This has never been more important as we work towards greater sustainability and following the UN Climate Change Conference (COP26) in Glasgow last November. Mending objects we love or find useful is also incredibly satisfying and good for our mental wellbeing.

However, once an object is accessioned into our collection, it’s no longer used for its original function and parts are no longer replaced unless absolutely necessary. Museums are in the business of conservation. While replacements already made are respected and conserved as part of an object’s story, new replacements are avoided where possible.

Principal Conservator, Stuart McDonald, tells us more about where a replacement part might be a good idea:

“From an engineering conservation point of view, there could be the occasion when we would replace parts of some of the working objects which were made in the museum. If parts wore out that were required to maintain the function of the object and keep it running, like bearings, we would replace them. We would record this in the files and mark the new part(s) with an ‘R’, identifying it as a replacement part. The original part would be labelled and kept in the collection.”

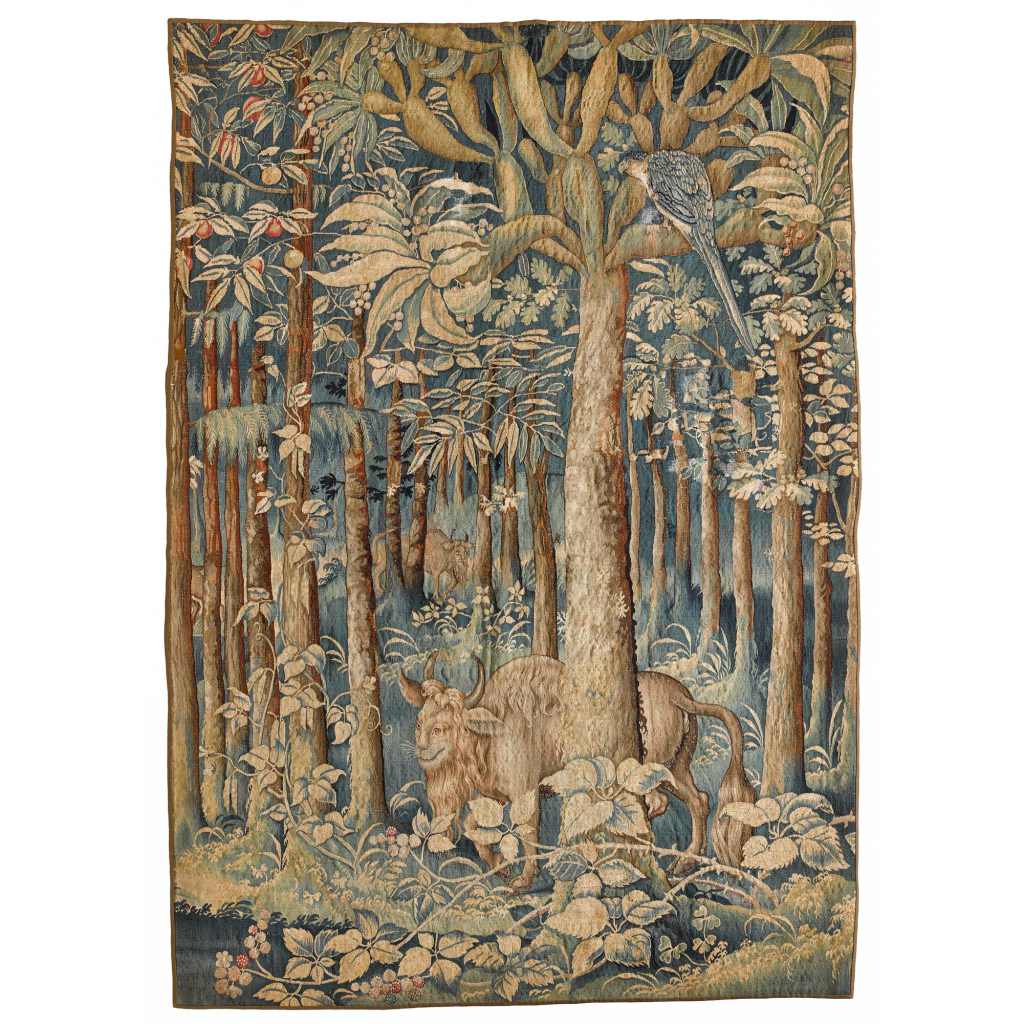

Replacements of sorts are also found in the galleries themselves. In Fashion & Style in particular, we have what’s called ‘rotations’. Light-sensitive objects (such as textiles) are replaced with another from the stores on a rotating basis to help reduce the amount of damage done to them by light while on display. By regularly replacing the objects, the gallery spaces are also renewed.

My interest in replacement is a personal one. Last summer, I was fortunate enough to have my left hip replaced. Ever since the Technology by Design gallery opened in 2016, I have purposefully walked by the three artificial hips currently on display to marvel at how these objects could be a part of someone’s body, or indeed my body.

Objects in museums help us understand ourselves better and explore what it is to be human. For example, searching our Collections Database for objects with replacements reveals a chair with a replacement seat; a salt-cellar with a new lid; bagpipes with new chanters; and replacement parts for an ethically sourced mobile phone.

I feel strangely comforted by these objects. They embody replacement and they’re doing just fine. Anthropomorphising objects in this way helps me make sense of the world and feel more closely connected with it.

Of course, replacements are not always the answer. An object can still be loved whether broken or repaired using only original parts. Whilst broken is often a beautiful and honest state (with archaeological finds and rock specimens in particular) repairs can also be celebrated. East Asian ceramics are famously repaired with kintsugi, and gold lacquer highlights the repair. Meanwhile, repairs on textiles are widespread, but that’s a story for another blog.