We all bring our own perspectives to the world we live in. Museum exhibitions are no different. When David C. Weinczok visited the Galloway Hoard exhibition, he was struck by its atmosphere and scale. He reflects on his journey through the space, uniquely informed by his own knowledge and experience.

I’m a big believer in the idea that knowing a few stories behind a place can enhance the experience of being there. Visiting somewhere, whether a historic site, a natural landscape or indeed a museum exhibition, you discover unexpected connections that might only ever occur to you. That’s pretty special.

I was lucky enough to see the Galloway Hoard exhibition at the National Museum of Scotland just before it opened (part of the privilege of working in the Digital Media team). This is my personal reflection on seeing these objects for the first time, bringing with me nearly a decade of studying and exploring Scotland’s story.

The first thing I noticed on entering the exhibition was the limited yet highly atmospheric use of light. It creates a hallowed environment, not unlike entering a cathedral or sacred space after dusk. Walking down the central corridor, my eyes were drawn to the illuminated peripheries where treasures beckoned me to appreciate them up close. There is an undeniable air of reverence throughout, but not in a stifling or sombre way. It fosters inquisitiveness, and leads to some truly wondrous moments.

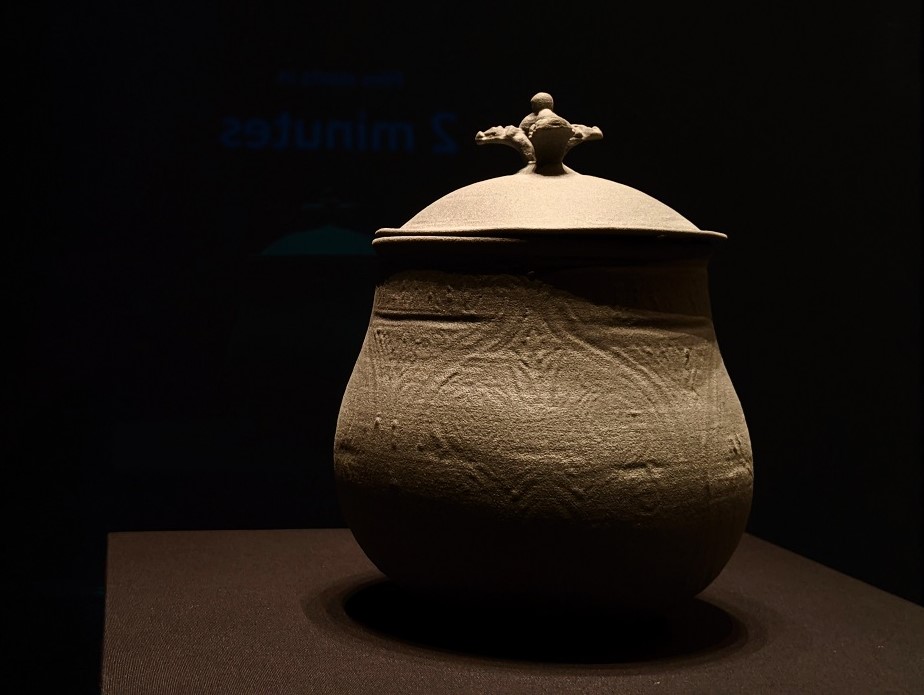

A silver vessel contained many of the Galloway Hoard’s hallmark objects and was separated into two distinct layers. The top layer contained the pectoral cross and was possibly intended as a decoy to convince plunderers that they had found everything worth taking. The lower layer contained a great many more treasures. Moving through the exhibition, I was struck by the feeling of advancing progressively deeper into a space of unknown depth and increasing mystery.

In a design partly responding to social distancing measures, the exhibition is largely unidirectional. You move through it going ever forward with objects being revealed in waves. Each section allows you to focus entirely on a specific object or set of objects, while the panels separating them replicate the excitable rush of an archaeologist making successive discoveries. In this way, the exhibition becomes a meta reproduction of the layered vessel itself.

If you pause to turn around, however, the objects seem to vanish. As though, once glimpsed, they recede back into the semi-mythical fog that characterises many peoples’ impression of the Viking Age. There was something else this layout reminded me of, but I couldn’t quite place it. Until, that is, I recently went to Orkney.

The Orcadian island of Rousay is known as the ‘Egypt of the North’ for the density and variety of archaeological sites it holds. In a coastal area of Rousay called Westness stands Midhowe Chambered Cairn, one of Scotland’s most impressive Neolithic tombs. Midhowe is the preeminent example of the Orkney-Cromarty type of chambered cairn, in which a long chamber is navigated through a single, central passageway with stall-like compartments on either side. To me, the Galloway Hoard exhibition designers created a space distinctly reminiscent of the Orkney-Cromarty layout more than 5,000 years after it was pioneered!

Back to the exhibition in Edinburgh, a striking contrast is achieved by the difference in scale between the objects themselves and the graphics that depict them. I was surprised at how small many of the best-known objects of the Galloway Hoard are, such as the golden bird pin and the pectoral cross. Held up on needle-thin supports against dark backgrounds, many of them appear to float as though possessing the powerful grace of a ballerina in tableau. The bird-pin especially seems almost perilously fragile. It conveys a potency out of proportion to its physical size that compels closer inspection.

On the opposite end of the scale, large panels with detailed close-up photographs of elements from individual objects make the imperceptible visible. Miniscule tool-marks on silver arm-rings, tiny scratches across the faces of enigmatic creatures, and wobbles on lines that appear straight to the naked eye are all magnified. To me, each mark or imperfection is a connection with the person behind the object. I wonder if the artisans would be flattered or horrified by this unprecedented magnification of their work?

Who is this? A figure on the pectoral cross, seemingly caught in some act.

Another figure on the pectoral cross. I can’t see it as anything other than a panda, despite that being highly unlikely.

One display contains colourful glass beads alongside a pinkish-brown, spherical rock crystal pendant bound by a thin metal casing. This sphere is an odd and intriguing object regardless, but the low lighting emphasises its subtle luminosity. The crystal seems to glow from within, as though containing some spark of magic. My first thought was that it could easily be one of the many MacGuffins in the Marvel Cinematic Universe (a fictional world that Digital Media previously had some fun with on Twitter).

Whoever possessed this object over one thousand years ago must also have held it in awe, though we’ll likely never know how exactly they would have articulated that. There is something beautiful in the thought that people separated by a millennium or more can find ‘magic’ in the same object, despite holding vastly different socio-cultural points of reference.

When people think of ‘Viking Age’ objects we often imagine swords, shields, ships and other martial expressions of material culture. The delicate sophistication of many of the objects in the Galloway Hoard challenges us to see the people of the past as complex individuals just as concerned with aesthetics, amusement and creativity as we are. This more relatable image is, in my opinion, closer to reality than the war-bent caricatures that pop histories too often indulge in.

I think that’s why the dirt-balls have resonated so strongly with many visitors, and with me. Yes, dirt-balls! Among all the glam of golden mementos, name-etched arm-rings, and quasi-mystical rock crystals are two balls of compressed earth. An odd addition to a hoard, you might think. Are hoards not meant to contain things of great value? Well, value is in the eye of the beholder.

Scientific analysis of the dirt-balls detected microscopic flecks of gold and even bone mingled through them: “hidden constellations”, to borrow a phrase from Dr Martin Goldberg, Senior Curator of Early Medieval and Viking Collections. Goldberg theorises that these dirt-balls could have been carried by a Christian pilgrim to holy sites. They would be rubbed in the dust around reliquaries to become deeply spiritual souvenirs.

Far from being an afterthought, to me the dirt-balls are one of the Galloway Hoard’s greatest treasures. If not in a material sense, then certainly in a sentimental one. I’m willing to wager that if the hoard’s owner (if indeed it had a single owner) was faced with the ‘burning house hypothetical’, these dirt-balls, would be among their top choices for what to save from the flames.

That was my experience of the Galloway Hoard. Each of you will bring your own unique perspective, knowledge and feelings to it, and my journey through it will fundamentally differ from yours. The information on display may be the same, but how it resonates with each person can be entirely unique. That’s the joy of museums.

Experience the Galloway Hoard exhibition for yourself and explore its story online.

David is a writer, presenter and historical researcher whose works aim to engage as many people with Scotland’s extraordinary stories as possible. Follow David’s adventures as ‘The Castle Hunter’ on Twitter.