The might of the Roman Empire is often likened to a shadow looming over the peoples along its ever-expanding frontiers. Yet, there is one place where this metaphor is inverted. As the winter sun sets behind the three peaks of the Eildon Hills in the Scottish Borders, it is the ambitions of Rome which are cast into shadow. In the second instalment of the six-part ‘Objects in Place’ series, historian, writer and Digital Media Content Producer David C. Weinczok takes you to the area around the Eildon Hills in the Scottish Borders.

The Eildons carry as many meanings as the number of hearts they have stirred. To Romans on the long march north along Dere Street, the appearance of the Eildons’ three peaks meant that safety and comfort was only a few hours’ march away. To the medieval monks of Melrose Abbey, the surrounding fertile fields were “God’s Acre”, a place for spiritual as well as material enrichment. To Walter Scott, who made his home at Abbotsford, it was a Romantic idyll brimming with tales waiting to be written down and shared with the world. More recently, Serbian-born textile designer Bernat Klein wove the colours and textures of this landscape into his fashions from his studio near Galashiels. Each person conjures their own version of this place, and none are any more or less ‘true’ than any other.

But where to begin? While nowhere near the ‘beginning’ of this place’s story, the remnants of Rome loom large within this landscape. Let’s start there.

The shadow of Rome: Trimontium

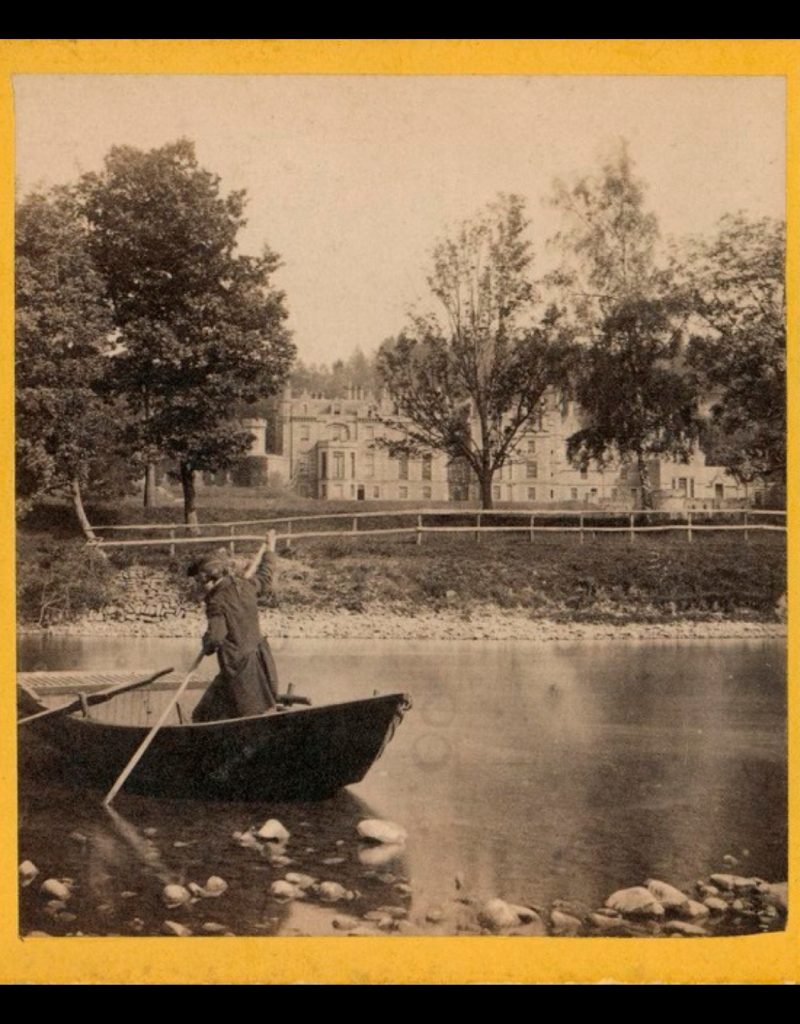

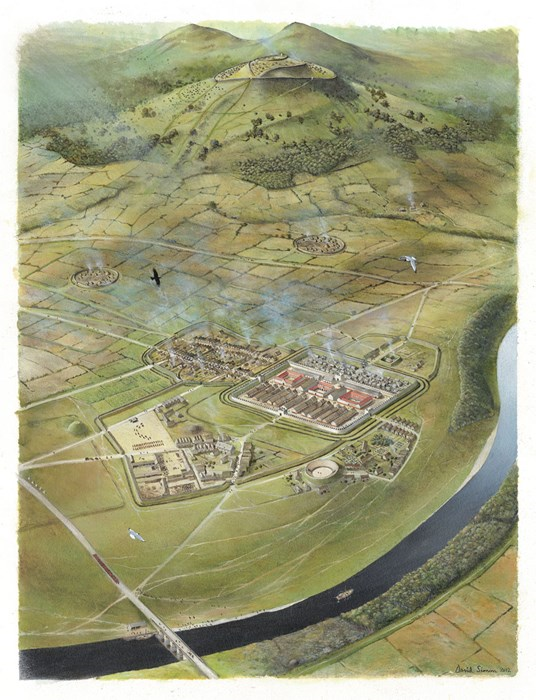

Named for the three high peaks of the Eildon Hills, the once-mighty Roman fort of Trimontium (meaning ‘triple mountain’ or ‘three peaks’) stood sentinel along the Tweed east of Melrose. It is also often referred to as Newstead, the name of the village overlooking it. This ghost of empire can be difficult to discern – when O. G. S. Crawford flew over it in 1930, he remarked that the sprawling fort was “almost invisible” after nearly two millennia of assaults from weather, stone plunderers, and the insatiable plough.

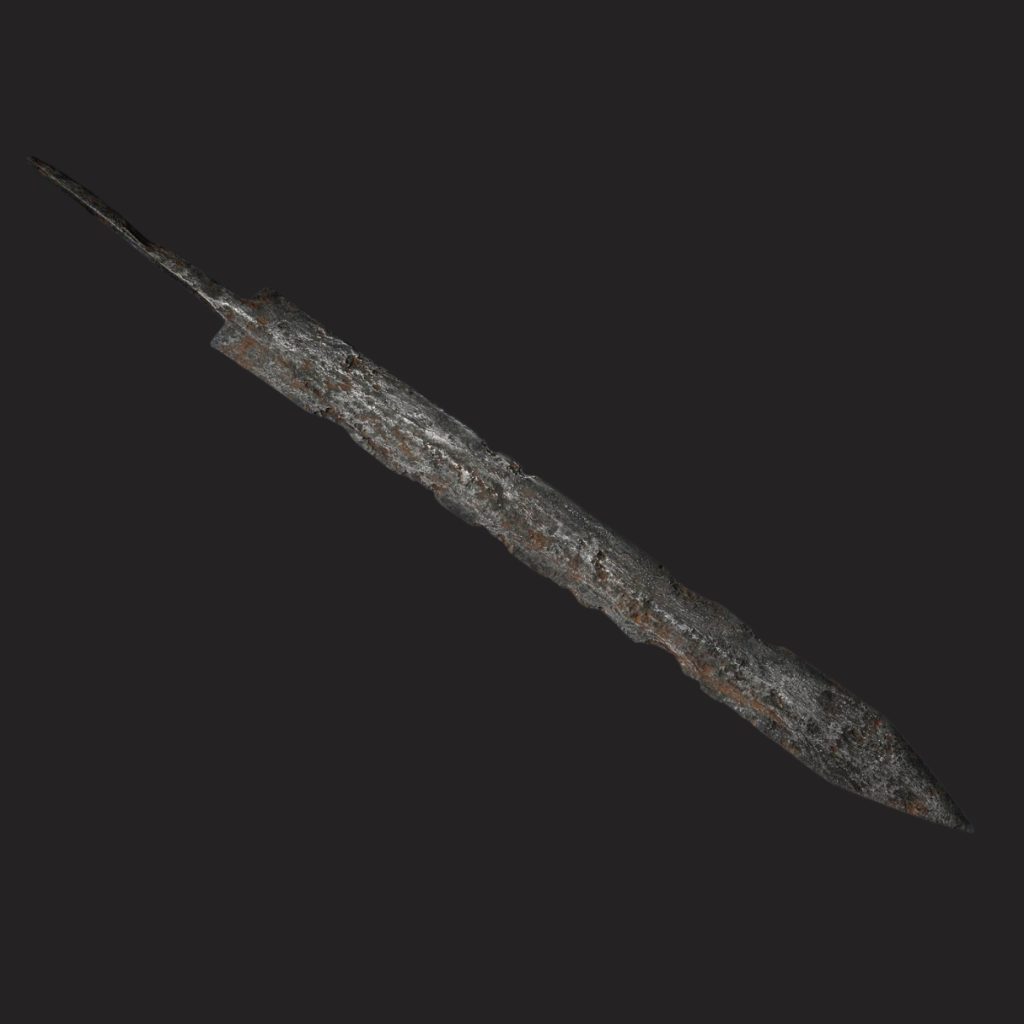

Archaeological excavations at Trimontium were carried out by Melrose solicitor James Curle between 1905 – 1910. Curle turned up one of the most important assemblages of Roman military equipment found anywhere in the Roman world. Finds included examples of the iconic gladius, a section of brass scale-armour, iron javelin heads, saddle mounts, and blacksmith’s tongs that still look almost like new.

Trimontium was occupied many times, with waves of construction, expansion, and deliberate destruction. The earliest fortified presence of the Roman army was a modest Agricolan fort established sometime in the early 80s AD during the first few years of Rome’s expansion into Scotland. Every major phase of Roman activity touched Trimontium, though some would-be conquerors such as Emperor Septimius Severus occupied adjacent temporary camps rather than the fort itself. At its height, Trimontium occupied a whopping 166 acres with the capacity to garrison the entirety of the 40,000-strong Roman army in Britannia.

Pageantry is an important part of the projection of power. A small hollow on the banks of the Tweed is all that remains of an amphitheatre that once held around 1,500 spectators. This was possibly the most northerly amphitheatre in the Roman Empire, though another site has been tentatively identified at Inveresk near Musselburgh 25 miles further north. In such places, mask and helmet-adorned cavalrymen could flaunt their skills and status to rapturous applause, riding horses decked out with leather chamfrons and colourful saddle-cloths.

However, Trimontium was not just for soldiers. Vast numbers of craftspeople, merchants, family members, and other civilians followed the legions like mobile townships. One touching survival is a leather child’s shoe, a testament to family life on the frontier.

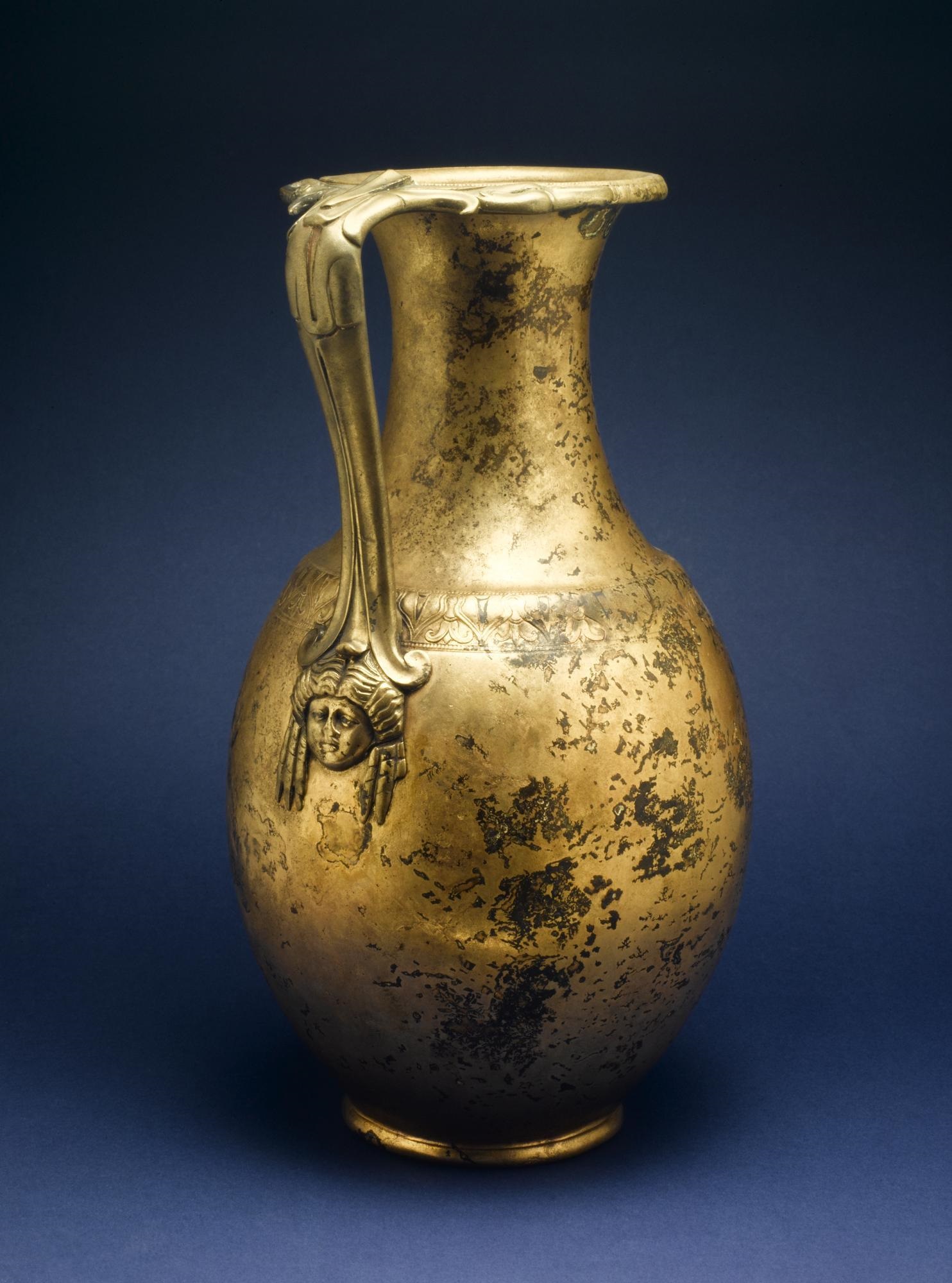

Huge quantities of food and drink were supplied to the fort, with wine being poured from decorative metal jugs. Trimontium’s occupants brought personal luxury goods with them, including tiny, delicate intaglios, an ornate necklace, and silver pendants. How often have you brought a symbolic personal item to work, or an unnecessary luxury on holiday? Past people were no different.

Friendlier companions could also be found on this frontier. Walter Elliot, a local fieldwalker, has recovered stamped tiles and bricks from Trimontium imprinted with footprints from various animals including dogs, sheep, shrew, and pigs. Some of the dogs were large, likely trained for tracking and military support roles, while others were small enough to have been personal pets. It’s easy to imagine one of these getting loose and causing chaos as it trod over freshly made, drying tiles! Though it must not have seemed that way to the irate artisan, those dogs were very good boys for securing their place in the historical record.

What precisely happened in the twilight of Roman Trimontium remains up for debate. Curle imagined a sudden, violent end, with native warbands overwhelming the walls, throwing down the buildings, and pitching the dead into vast pits. Clearly thinking along similar lines, Arthur Conan Doyle – best known as the creator of Sherlock Holmes – wrote a short story, ‘Through the Veil’, in which a married couple visit the long-vanished fort and relive past lives as participants in its violent destruction. Yet this is just one interpretation, and there is also a case for Trimontium being peaceably abandoned. You can learn much more about the Romans at Trimontium, as well as the local peoples they engaged with, in the National Museum of Scotland’s extensive Early People galleries and by visiting the Trimontium Museum in Melrose.

Many others would have wondered at Trimontium’s ruins en route to their own places in history. Two centuries after the legions left Britannia, the people living in Din Eidyn, which later became Edinburgh Castle, sped past it along Dere Street to meet defeat at the hands of the Northumbrians in the Battle of Catraeth (modern Catterick in north Yorkshire). Norse warbands used the network of Roman roads in the Borders to give speed to their raids, and in 1298 Edward I of England marched his mighty host through here on several campaigns of fire and sword. Did the fading memory of Rome spur Edward on, or serve as a humble reminder of the fate of all great conquerors?

Torwoodlee Broch

Torwoodlee Broch is one of very few brochs in southern Scotland. Its roughly 2,000 years-old, overgrown foundations are still visible on the eastern slope of Mains Hill above Torwoodlee Tower, west of Galashiels. Of all the ‘native’ fortified sites around Trimontium, Torwoodlee Broch has yielded the greatest quantity of imported Roman goods. These archaeological finds hint at a much more complex relationship between locals and the Roman invaders than the traditional narrative of pure antagonism portrays.

The finds include various types of glassware, sherds from amphorae used for Spanish olive oil and Egyptian preserved fruits, and a Romano-British copper alloy ‘trumpet brooch’. The landmark 2012 publication A Roman Frontier Post and its People: Newstead 1911-2011 notes that this was a two-way street: numerous objects produced by people native to the area ended up in the hands of Romans in Trimontium, too.

However, hints of conflict with Rome are not entirely absent. One recent hypothesis is that a local chieftain redeveloped the hillfort at Torwoodlee into a broch-like structure sometime between 117 – 139 AD. Torwoodlee Broch was systematically destroyed just a few years after being built – could this have been an act of retribution by Rome? It’s possible, but our experts think it just as likely that Torwoodlee was destroyed as a result of local political intrigues. Not everything that happened in ‘native’ societies was in response to, or the result of, Roman incursions. In many ways, life went on as usual with all the ups, downs, rivalries and ambitions that entails.

The Eildon Hills

In legend, the Eildon Hills are ‘hollow hills’ concealing otherworldly treasures and sleeping warriors within. Many will be familiar with the story that King Arthur slumbers in the depths of Arthur’s Seat, Edinburgh, but the Eildons also claim him. They may not be hollow, but again like Arthur’s Seat they are the remnants of a vast, prehistoric volcano whose vent was plugged millions of years before the first people filled them with stories.

There are four hills in the Eildons – Eildon Hill North, Eildon Mid Hill, Eildon Wester Hill, and a relatively tiny outcrop fittingly called Little Hill. Yet, depending on the direction you approach them from, the peaks seem to fuse and split like shape-shifters. Standing atop the summit of Eildon Hill North watching its mid-winter shadow engulf the grounds of Trimontium, a poem occurred to me which speaks to this strange effect:

From the West rise the three,

From the North stand but two,

From the East rules the one —

King of Shadows in the winter sun

Borders lore tells how the famous medieval purveyor of prophecies, Thomas the Rhymer, joined the court of the Fairy Queen inside the Eildons. He dwelt there for seven years and was given a magical apple which gave him the gift of prophecy. One of his predictions was that the Atlantic and North Sea would one day meet through Scotland, which arguably came true with the completion of the Caledonian Canal in 1822. The fairy folk of the Eildons allegedly hoarded so much treasure that nineteenth century storytellers told how the teeth of sheep grazing the hillsides would glitter yellow!

The Eildons’ slopes have yielded very real treasures. In 1982 a group of seven Bronze Age socketed axes were discovered by metal detectorists on Eildon Mid Hill near the path leading past the ancient and curiously named quarry of Bourjo. This same site likely supplied stones for use in the medieval development of Melrose Abbey.

The top of Eildon Hill North itself reveals few archaeological traces to all but the most trained eye. However, during the Bronze and Iron ages the hilltop was positively urban. Nearly 500 hut circles supporting timber-built structures once stood here, making Eildon Hill North one of the largest hillforts in Scotland. A conservative estimate of the number of people that the enclosed summit area could have contained at one time is 3,000.

The big debate around Eildon Hill North is whether it was a permanently occupied site, or a gathering place at specific times of year. Anyone who has climbed any of the Eildons can attest to their windswept nature, and conditions at the top can seem almost sub-Arctic. Adding to the mystery is the confirmed presence of a Roman watchtower. Could the hillfort have been abandoned at some point during the Roman occupation of Trimontium? Or was it actually in use long before and well after the legions staked their place? Excavations during the summer of 2022 hope to untangle this web once and for all.

The visual range from the summit of Eildon Hill North is astonishing. Countless monuments from across the ages are clearly visible, including the fanged ramparts of Hume Castle nearly twelve miles to the east and the slim tower of Smailholm where a young Walter Scott revelled in the romance of a storm. From these heights even Melrose Abbey – so grand and wealthy and powerful – appears a miniscule plaything, a reverent doll’s house.

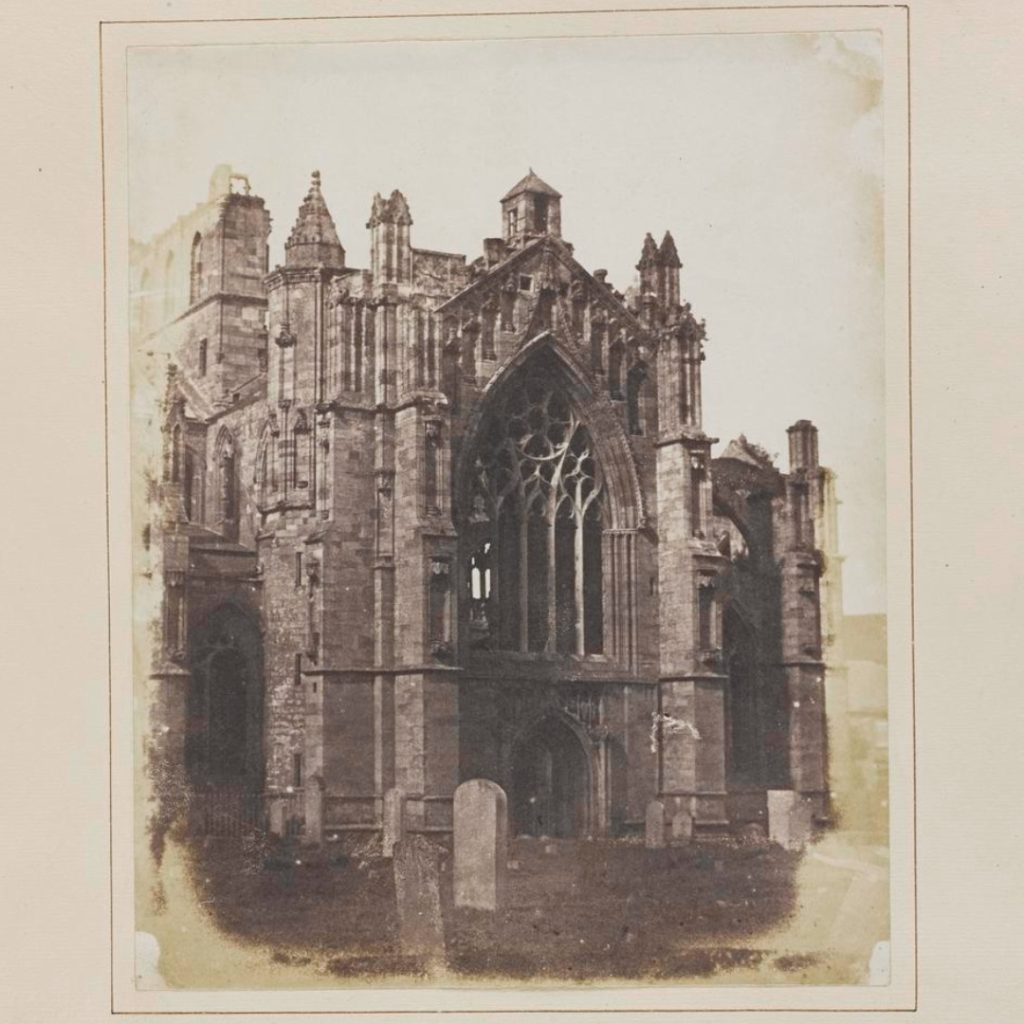

The mystery of Melrose Abbey’s mummified heart

While there are relatively few objects from Melrose Abbey in our collections, National Museums Scotland did play a role in one of the best-known episodes from the abbey’s medieval history: the burial of King Robert Bruce’s heart.

Knowing his death was imminent, in 1329 King Robert gathered his most loyal and trusted companions and wished for his embalmed heart to be taken on Crusade to Jerusalem. The story of its epic journey is one for another day, but on its return to Scotland it was buried somewhere on the premises of Melrose Abbey while Bruce’s skeleton was interred at Dunfermline Abbey.

In 1921 a lead canister was discovered near the northwest corner of Melrose’s chapter house. Details of the find can be found in a 2010 article in the Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, brilliantly titled ‘Graveheart’. The canister was sent to the National Museum of Scotland, at that time called the National Museum of Antiquities of Scotland, and a ‘mummified’ heart was found within. Experts doubted that it was Bruce’s due to the canister being found in a relatively unceremonious location, but the news got out and imaginations fired up.

The canister containing the maybe, maybe-not heart of Robert Bruce was reinterred at Melrose Abbey later in the 1920s, excavated again in the 1990s, and laid to rest once more on 22 June 1998 with international media coverage. This rode the coattails of an eventful few years in Scottish national identity – Braveheart hit cinemas in 1995, the Stone of Destiny returned to Edinburgh in 1996, and the 1997 National Referendum resulted in the re-establishment of a Scottish Parliament for the first time in nearly three centuries in 1999. The Scottish Secretary at the time, Donald Dewar, remarked, “We cannot know for certain whether the casket buried here contains the heart of Robert the Bruce, but in a sense it does not matter; the casket and the heart are symbols of the man.”

As with all good stories, there are elements of truth and causes for doubt – a fitting summary of the study of history if ever there was one. Chances are that the telling will endure long beyond the knowing.

A cyclical landscape

There is something beautifully cyclical in tracing how elements of this landscape were used and re-used. Gravel from the River Tweed was taken in vast quantities to make the orderly streets within and around Trimontium. In turn, red stones from the fort are said to have gone into the Scottish Baronial mansion of Drygrange, across the River Tweed near the Leaderfoot Viaduct. In 1891, excavators at Torwoodlee Broch estimated that some 200 cartloads of stone had been removed from the site to build field dykes earlier that same century, a time when the formal enclosure of agricultural lands was in full swing. Torwoodlee Broch is itself built on the site of an earlier hillfort, with one of its ditches cutting through earlier earthworks. While likely apocryphal or at least exaggerated, residents of the village of Newstead say that after Melrose Abbey was heavily damaged during the Rough Wooing in 1544 and 1545 many of the abbey’s stones were incorporated into local homes.

These cycles of re-use and re-interpretation turn the lands touched by the shadows of the Eildon Hills into a vast Ship of Theseus. Any one place’s origins are inextricably tied with another’s demise. The philosopher Graham Harmon defines the concept of a ‘landscape’ as, “any object that links a wide variety of other objects that all use it as a mediator.” Viewed in this way, there is far more connecting the disparate ages represented by objects in our collections than there is partitioning them into their own neat categories. Once we come alive to this interconnectivity, a place pulses with possibilities and personal meanings. Walter Scott was attuned to this, as were the Romans, the monks of Melrose, and the thousands of people lost to the historical record who lived rich and complicated lives in the shadow of the Eildons. With that in mind: what does this place mean to you?

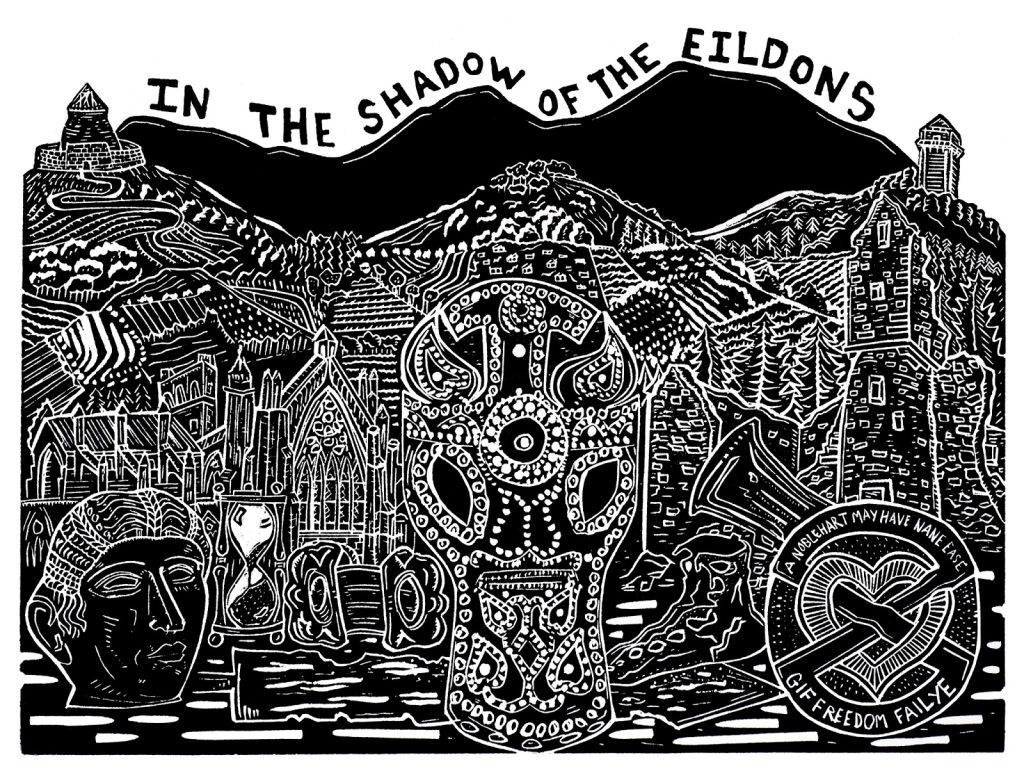

Watch the creative process of Pamela Scott, creator of the linocut, in the time lapse video below.

The six-part Objects in Place blog series will continue in February, with part three zooming in on more than 5,000 years of history along the Eynhallow Sound, Orkney. Part four will go to Stirling, the embattled heart of Scotland. Part five will look out from the walls of Tantallon Castle, East Lothian. Part six will bring the series to a conclusion with a place very close to us – Greyfriars Kirkyard in Edinburgh. Dundee-based illustrator and printmaker Pamela Scott has been commissioned to produce a unique artwork for each installment. If you haven’t already, read part one about Kilmartin Glen, Argyll, here.

The six-part Objects in Place blog series will next head to Stirling, the embattled heart of Scotland. Part five in goes to Tantallon Castle, East Lothian, and part six will bring the series to a conclusion with a special place very close to us – Greyfriars Kirkyard in Edinburgh. Dundee-based illustrator and printmaker Pamela Scott has been commissioned to produce a unique artwork for each installment. If you haven’t already, read part one about Kilmartin Glen, Argyll, here, and part two about the Eildon Hills and Melrose here.