In 2019 I received a travel fellowship to the Association of Art Museum Curators & AAMC Foundation conference in New York, with subsequent follow-up funding also supported and coordinated by Art Fund. Using information and contacts gained at the conference, I scheduled visits to museums and art galleries in Ottawa and Toronto displaying indigenous collections, and arranged meetings with museum professionals and academics actively engaged in collaborative working with indigenous communities. As well as learning from colleagues’ experiences and seeing examples of best practice, I also hoped to raise the profile of National Museums Scotland’s indigenous Americas collections.

I met over twenty colleagues from the Royal Ontario Museum, Art Gallery Ontario and Bata Shoe Museum in Toronto, and the Canadian Museum of History and National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa; academics from OCAD University in Toronto and Carleton University in Ottawa, and the directors of OCAD University’s Onsite Gallery, and the Indigenous Art Centre, part of the government department of Corporate Secretariat Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada. Several colleagues were of indigenous ancestry, and everyone gave me valuable insights into working with and representing indigenous communities in museums and galleries. I heard many different perspectives and experiences, and received both encouragement and resources with which to further develop National Museum Scotland’s interpretation.

Almost everyone I met mentioned the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (2015), and its impact on museums and galleries in Canada. Historically, the relationship between the Canadian state and indigenous peoples has been fraught with conflict and the Commission sought to address this, in particular the Indian Residential Schools system, which existed from the 1880s to 1996. Under this system, more than 150,000 indigenous children were forcibly removed from their families, denied their traditional languages, dress, beliefs and cultural identity, with an enforced Christian education to “civilise” and “assimilate”, “to kill the Indian in the child”. Abuse was rife, and mortality rates high. Results of this enquiry included financial compensation for survivors, and 94 ‘calls to action’ issued by the Government. Alongside the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (2007), museums and galleries’ subsequent policies now include increased education and commemoration of indigenous histories, as well as increased access to collections and archival material. In practice this also includes repatriation, community consultation, increased indigenous representation in the workforce, and increased cultural sensitivity and awareness. For example, between 1884 to 1951 Government legislation made indigenous ceremonies such as the potlatch, powwow and sun dance illegal, and regalia and other material seized during raids is now found in museums across the world; in recognition these are now increasingly being made available for community visits and repatriation requests.

My first visit was to Bata Shoe Museum in Toronto, and Manager of Exhibitions and Assistant Curator Nishi Bassi was very helpful in sharing her experiences of beginning the process of decolonising the museum, and reassessing previous more traditional approaches to interpretation and display. The on-site open storage of over 13,000 shoes was visually stunning, as founder Sonja Bata intended; particularly of interest to me were the Arctic collections and the current exhibition on ‘Art and Innovation’ of Arctic footwear. The Bata collection was acquired with a strong focus on decorative techniques, materials and design; National Museums Scotland’s Arctic and North American collections complement these with our historic, often more utilitarian examples, with known history and provenance.

Quillwork and beadwork footwear in open storage at The Bata Shoe Museum, Toronto.

The Royal Ontario Museum is comparable to National Museums Scotland in being an encyclopaedic museum, with a broad range of collections from the impressive dinosaur skeletons, through natural history and decorative arts, to world cultures. The Daphne Cockwell Gallery dedicated to First Peoples art & culture was reopened in 2018 in a better location and with free entry to encourage access. When I visited, they were recruiting for a Curator of Indigenous Art and Cultures, with an expectation that the successful candidate would reshape the displays of indigenous material, and steer the museum forward in terms of reframing indigenous material within the ‘Canadian’ history galleries, as well as building relationships and increasing reach beyond the institutional walls. They will be well supported by the Learning Department, including J’net Ayayqwayaksheelth, Indigenous Outreach and Learning Coordinator.

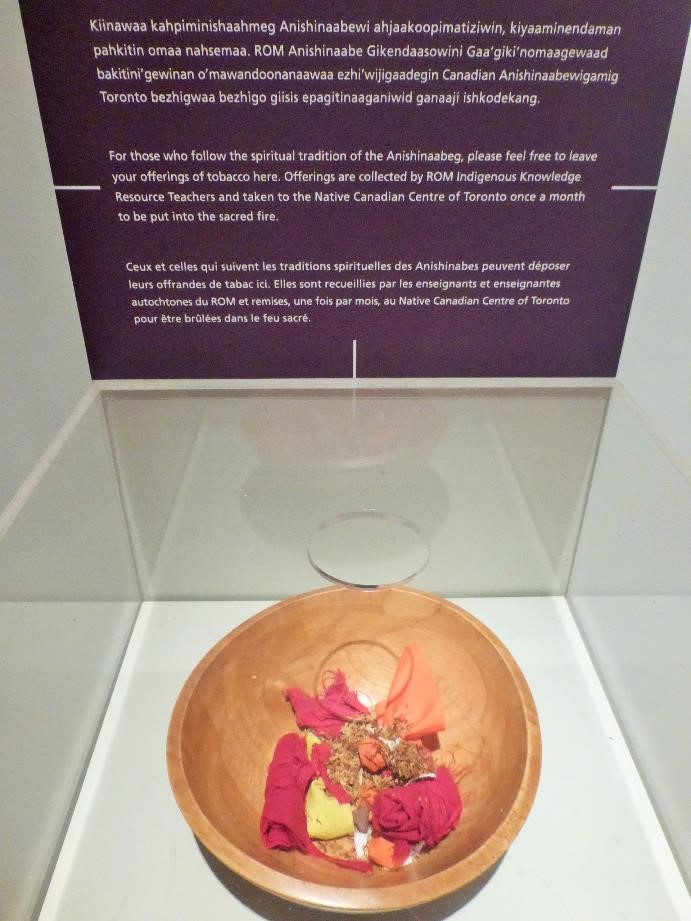

J’net made a particular impact on my trip, as she combines passionate beliefs with practical innovative approaches to making both collections and indigenous knowledge accessible, such as daily gallery interactions, staff training, and regular Facebook Live ‘Indigenous Insights’ facilitated by indigenous colleagues, volunteers, and members of the museum’s Indigenous Youth Cabinet. She spoke forcefully on the importance of changing institutions from the inside, with the support of management, leaders and politicians; offering opportunities to indigenous people, and continuing to address social inequalities. Changes that might appear small, such as updating the claim that ‘Christopher Columbus Discovers America’ on a historical ‘tree cookie’, and installing a tobacco offering box in the First People’s Gallery, actually represent larger changes in attitude within the institution, although work is ongoing.

One of my most anticipated visits was to the Canadian Museum of History, where eight colleagues were very generous in sharing their time with me. With the Westminster-inspired architecture of the Canadian Parliament looming over the river and visible through the many plate-glass windows, and the imminent federal election making many people nervous about changing political priorities, it did seem that both here and at the nearby National Gallery of Canada, strong political influences shaped their messaging and displays, perhaps even more than at the other institutions I visited. The Canadian Museum of History has run an Indigenous Internship Program for an impressive 27 years. Interns are of all ages and at various life stages, including both the start and end of their careers. As well as the Indigenous Advisory Committee (one of six advisory committees), positions on the Board of Trustees are reserved for First Nations, Inuit and Métis representatives.

The magnificent museum and storage buildings were designed by renowned indigenous architect Douglas Cardinal, who also designed the National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, D.C. The most well-known gallery is the Grand Hall, which houses an impressive collection of carved poles (often incorrectly called ‘totem poles’), as well as reconstructions of six North West Coast houses, containing historical and contemporary art, regalia, tools and equipment. Behind the Grand Hall are the meandering galleries of the Canadian History Hall, where indigenous creation stories, mythologies and personal experiences are given equal gallery space to more Eurocentric chronologies, highlighting diverse perceptions of time, origins and history.

I met colleagues from both the Curatorial and Repatriation and Indigenous Relations departments, who offered insights into the many challenges and rewards of caring for a national collection with complex and evolving histories. Three curators generously shared their experiences of designing an exhibition in collaboration with indigenous participants. They reiterated the importance of investing substantial time and resources for the reciprocal benefit of both the museum and indigenous communities, building respectful and meaningful relationships, and being clear and realistic about the expectations of all involved.

I wasn’t sure what to expect from the Indigenous Art Centre, as it’s more of a government department than a visitor attraction, with only a small temporary display space in the lobby. In fact, this is a huge and under-used resource of indigenous art, collected since the 1960s, and available for long- and short-term loan to national and international exhibitions. Actively collecting with an indigenous board and director, it has always reflected current trends and emerging artists, quite distinct from collections in larger institutions which target mature works by established artists, often selected in comparison to the European canon. For any curators looking to borrow contemporary indigenous art, this is an excellent resource with great potential for the future.

Unfortunately the timing of my visit to the National Gallery of Canada just missed the opening of Àbadakone | Continuous Fire | Feu continuel, the second of a series of exhibitions of international contemporary indigenous art. However, the permanent galleries more than made up for this. Recently redisplayed and opened in 2017, through judicious use of loans (many from the nearby Canadian Museum of History), the juxtaposition of historic settler and indigenous art creates dialogues of trade and influence. A large birch bark canoe in the centre of one gallery signifies the indigenous presence missing from the iconic landscapes of the Group of Seven artists. The entrance to the Canadian and Indigenous galleries houses a striking mixture of historical and contemporary indigenous pieces, including contemporary pieces made using traditional techniques, themes and symbolism, to challenge the viewer’s perception of what is old and new. Although not all of the objects’ histories are described, nor the selection processes explained, Alexandra Kahsenni:io Nahwegahbow, Associate Curator of Historical Indigenous Art explained that the Gallery continues to work closely with two Indigenous Advisory Committees on how to welcome and care for historical artefacts that are seen as direct embodiments of ancestors. Further information on this ongoing relationship can be found in an article here.

Entrance area to the historical galleries at the National Gallery of Canada, including contemporary and ancestral pieces.

Birch bark canoe in front of works by Canada’s famous Group of Seven artists in the National Gallery of Canada.

The Art Gallery Ontario has several outstanding galleries of indigenous artists’ work, unflinchingly dealing with issues of identity, colonialism and social inequality. I saw evidence of appreciation of this on a feedback card apparently written that day, which read: “I’m happy to see my indigenous peoples expressions and realities in the same space of a lot of those people who denied them that right. We still have plenty to say and plenty to share.”

Although classified together as ‘Indigenous and Canadian art’, works by indigenous artists and settlers are generally hung in separate galleries, with the exception of a few cases of three-dimensional indigenous material amongst the settler paintings. A couple of juxtapositions did speak eloquently though, such as two works by Group of Seven artist Lawren Harris (1885–1970) inserted amongst politicised contemporary pieces by indigenous artists. The accompanying label described how Harris’ “vast and unpopulated vistas…helped reinforce colonial narratives of the country as an expansive and untouched terrain”. In one of the first galleries near the entrance, Emily Carr’s iconic untitled work, previously called ‘Indian Church’ (1929) and recently renamed ‘Church in Yuquot Village’, faces Sonny Assu’s ‘Re-Invaders: Digital Intervention on an Emily Carr Painting (Indian Church, 1929)’ (2014). Both paintings dramatically flank Adrian Stimson’s ‘Old Sun’ (2005), a powerful installation combining buffalo skin, steel, sand, a light from the Old Sun Residential School, and an ominous shadowy representation of the British Union flag.

At the Ontario College of Art and Design (OCAD) University’s Onsite Gallery, I visited a temporary exhibition of indigenous art from around the circumpolar world, entitled ‘Among All These Tundras’. I joined a tour led by Ryan Rice, independent curator and Associate Dean, and before the tour he told me about his previous roles representing indigenous artists and curators. Although he remained critical of many major galleries and museums, “doors were now opening, and getting wider”. He explained how smaller independent galleries such as Onsite can often offer more opportunities to emerging indigenous artists, although perhaps the same could be said for non-indigenous artists as well.

My penultimate meeting was with Professor Ruth Phillips, Co-director of Great Lakes Research Alliance for the Study of Aboriginal Arts & Cultures (GRASAC), and Canada Research Chair in Modern Cultures at Carleton University. An authoritative figure, she was reassuring in her position that the perspectives of indigenous artists and non-indigenous academics were both valid, as long as both are grounded in respect, with ongoing dialogue and exchange. She emphasised the importance of research, particularly into provenance, and the complexities of repatriation for artefacts acquired as diplomatic gifts and trade items. Echoing Dr Tim Foran, Curator of British North America at the Canadian Museum of History, she highlighted the nuances of trade and personal relationships, intermarriage, gift-giving and obligation, and the dangers of emotive generalisation and absolutism.

Nowadays much can be learnt through digital exchange, collaboration, and consultation with both historical archives and contemporary specialists. Ancestral knowledge, practical skills, techniques, and traditions can be rediscovered and re-understood, reconnecting generations, communities, and individuals around the world. Finally, she emphasised the Reconciliation aspect of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission; that the real gains are now to be made in working together, rather than perpetuating divisions.

This trip was a fantastic opportunity to immerse myself in some of Canada’s pre-eminent museums and galleries, to meet practitioners leading the way in representing and integrating both indigenous and settler perspectives into core narratives and displays. As museums continue to confront the legacies of empire, and as we all face global issues of health and climate chaos, this research trip to Canada reinforced for me the importance of putting communities, collaboration and communication at the heart of everything we do.

This trip was made possible with support from the Association of Art Museum Curators & AAMC Foundation and Art Fund.

This article originally appeared on the Museums Ethnographers blog.