Today metals are all around us. We use them for cooking and eating, for decorating our bodies, for building cars and skyscrapers, for performing surgery, and for many other things besides. Without a doubt metals form a significant part of whatever device you are reading this on.

But imagine encountering metal for the first time. Imagine trying to understand this material that was unlike any other you’d seen before. A material that shines like the sun. A material that turns to liquid and glows when you heat it and solidifies again when you cool it. A material that you can recycle and turn into different shapes. A material that changes your world.

The first metals were copper, tin and gold. These were introduced into Scotland around 4500 years ago, during a period we call the Chalcolithic, or Copper Age. These first metals were rare materials that were hard to acquire. Gold and tin probably came from south west England; copper came from Ireland and central Europe. This required new trade and exchange networks, connecting people across Britain, Ireland and Europe, and needed people with specialised knowledge and skills to turn the raw materials into ornaments, tools and weapons.

Early gold objects were made by carefully hammering and decorating gold sheet to produce decorative adornments, such as gold collars called lunulae and basket-shaped ornaments which may have been ear-rings or hair ornaments. Over time goldworking became increasingly specialised but it continued to be a prized material for displaying wealth. Gold has clearly always been a special material.

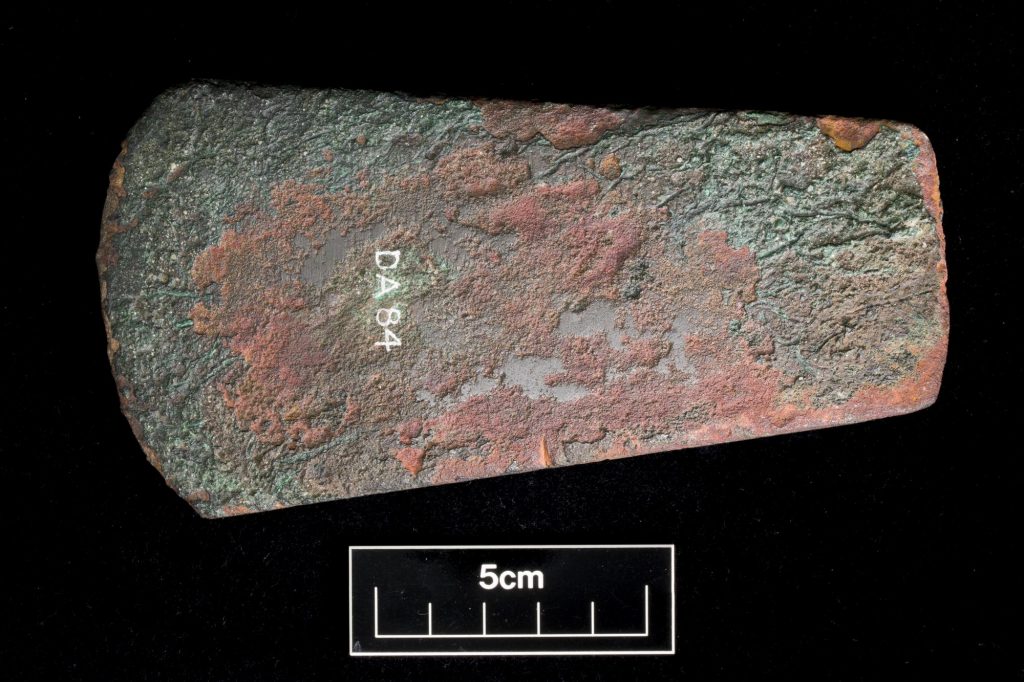

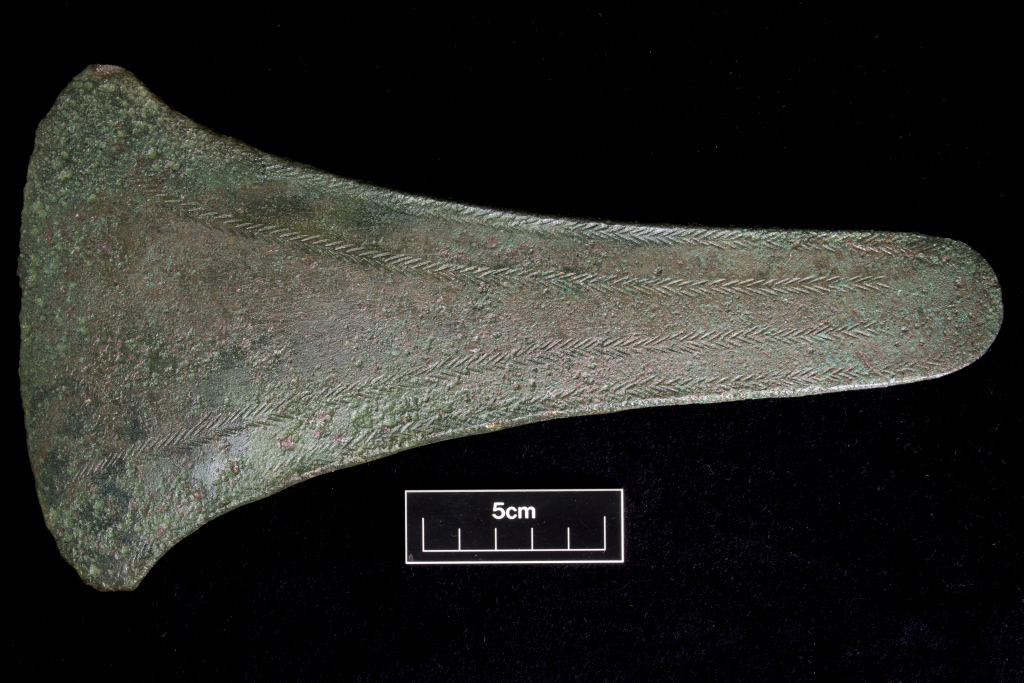

The earliest metal tools and weapons were made from copper during the Chalcolithic, and then from bronze after about 2150 BC, when the true ‘Bronze Age’ began. These metals required extracting and smelting ores to acquire the raw material and then casting it into the shape of the desired object. The clearest evidence for tool production from Scotland can be seen in stone moulds for axes. Copper or bronze was heated to over 1000 degrees Celsius, melted in a crucible and then poured into a prepared mould. We have several such moulds in our collection, and it seems that by about 2000 BC Scotland was an industrious region for producing axes. Once out of the mould, the axes were then hammered, shaped and sharpened by skilled craftspeople, and fitted on wooden hafts, ready for use. Production of the moulds, tools and the axes required a complex set of skills involving many different materials; knowledge of fire, lithic technology and woodworking would all have been essential. So, when we talk of ‘metalworking’ we should see this as a multi-craft practice, perhaps by a single craftsperson, or else involving multiple individuals with different skillsets right from the beginning. The metalworkers, with their specialised knowledge, would have been important and integral to local communities.

Copper axes, like this one from Lhanbryde, Moray, were some of the earliest metal artefacts produced.

A sandstone mould from Culbin Sands, Moray, used for casting axeheads and other objects

But who were these first metalworkers? Unfortunately, we don’t have clear evidence of ‘workshops’ or clear sets of tools linked with people in Britain so we have to approach this by looking at how and where the objects were buried and other changes happening at this time.

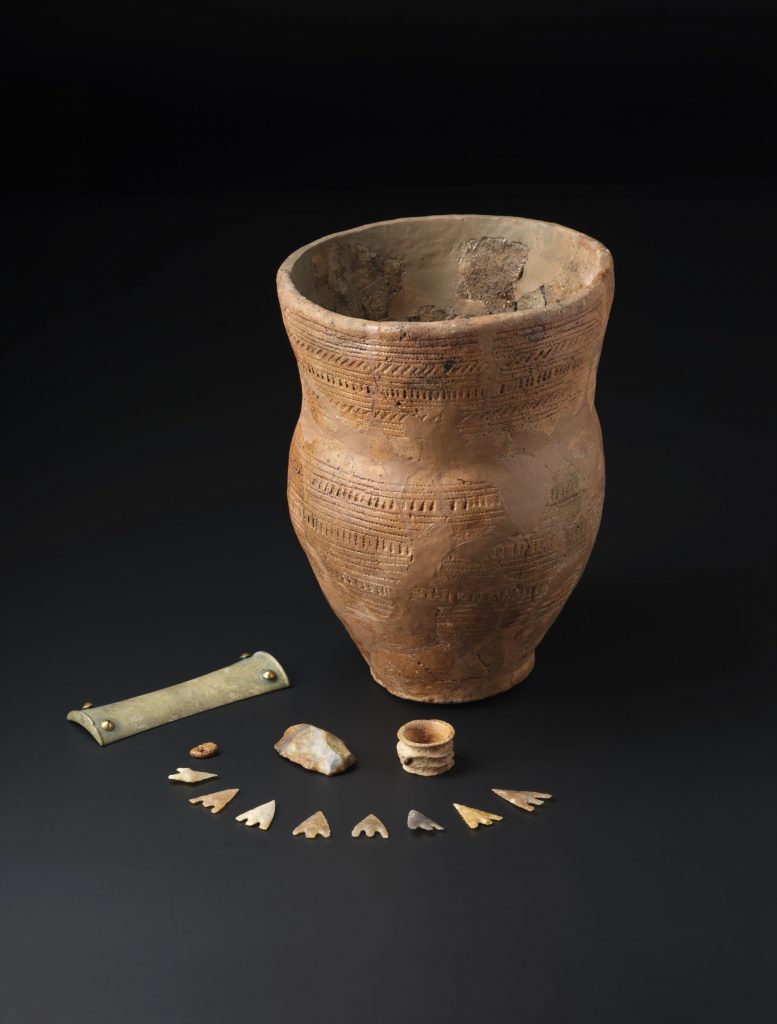

The Chalcolithic is a period defined by the introduction of metal but really it is about the arrival of new technologies, new people and new ways of life. It is a period of social and cultural change. Knowledge of metalworking was just one part of this, which came with travelling people. These people, the “Beaker People”, are in fact named after their characteristic pottery style and isotopic and ancient DNA analysis has shown people travelled in small groups to different parts of Britain from Ireland and mainland Europe. This happened incrementally over a long time and the archaeological evidence suggests these new people integrated with local populations as wider ideas surrounding burial practices and metalworking were adopted and adapted. These ideas transformed over time and gradually became part of the normal cultural repertoire for local communities living in Scotland. One of the earliest and most important graves from around 2200-2000 BC in Scotland was found at Culduthel, Inverness, where an adult male was buried with a large Beaker (which would have contained some kind of drink), eight fine flint barbed-and-tanged arrowheads, a bone ring (possibly for a belt or for a quiver), an amber bead, a flint strike-a-light and a stone wrist guard with gold rivet caps. All of this signals the importance of this person. Isotopic analysis shows this person probably grew up in Ireland, an early source of copper, and moved to Scotland later in life.

When the first metal objects arrived and were produced, they would probably have been reserved for individuals of higher status within society. Burials like Culduthel allow archaeologists to interpret this from what was included with the dead. This includes metal objects such as daggers alongside pottery, archery equipment and jewellery produced from jet and amber; these objects speak of craftworking skills and symbols of status. As metal objects became more common, more elaborate forms also emerged. Beautifully decorated axes were produced, such as a large axehead from Nairn. These were rarely buried with the dead and instead deposited as single finds or in hoards, sometimes with jewellery, often in significant landscape locations such as mountains and river valleys.

The production, use and treatment of metal gives us a wonderful glimpse of its importance to Chalcolithic and Early Bronze Age societies. The first metalworkers had a tremendous impact on how people engaged with and shaped their world, which was linked with wider social changes, including the arrival of new groups of people and the introduction and transformation of new ideas relating to burials and pottery. The metal objects that surround you today owe their origins to those first metalworkers and the gold, copper and bronze artefacts they produced 4500 years ago.