While working at the National Museums Scotland I had the privilege to lead on the Dan Klein Collection Conservation project. Over the span of two years, I brought together a team of seven talented and inspired conservators who made the realization and the completion of this project possible.

It all started when I was called upon to undertake a preliminary condition assessment of part of the collection in 2017 by the curator Sarah Rothwell. She showed me a number of artworks, in a variety of scales and processes, which had – at some stage before arrival into the Museum – been physically damaged. Most of the objects required extensive conservation treatments to provide structural stability, safe handling and to make them suitable for potential future display. We decided that this project presented us with the unique opportunity for collaboration between conservators, conservation students, National Museums of Scotland curators and the artists themselves.

The project also included students, from both UCL London and West Dean College of Arts and Conservation, who we hosted as part of their training, and have since gone on to work in conservation labs across the globe. I’ve learnt from our students, as much as they’ve learnt from me – every conservator has their own unique ways of approaching conservation issues and creative problem solving. Our work is not only about structurally fixing an object or prolonging the life of the material it is made from. It is also about uncovering the story behind an object, and what gives it its soul. Or how an artefact can tell us about the maker themselves, and what they may or may not be looking to express through their art.

For me this is the moment in my work which always reminds me why I love the conservation profession. There will be no end to this blog if I start telling you about the remarkable work of my team of artefact conservators who were part of the Dan Klein Collection Conservation Project. They all displayed creativity and flexibility in their approach to the task, as well as consideration for the often-complex material, cultural and contextual aspects of the artist’s work. But no one can tell their stories better than themselves, which I hope you have been reading in the series of blogs that have come before mine.

No ordinary specs

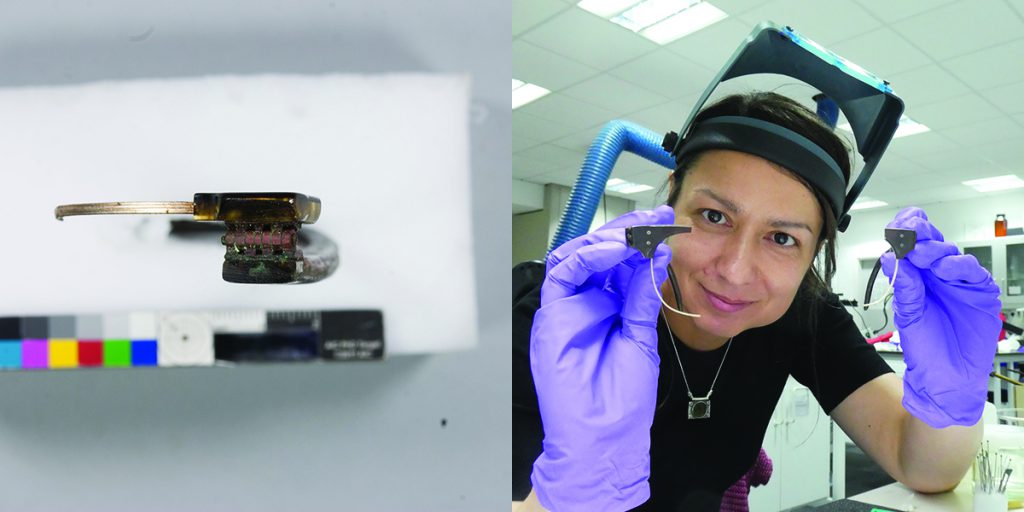

Now I would like to share my own experience of conserving two artworks as part of this project. One of these was an artwork entitled ‘Venetian Blind’ by Charlotte Hughes-Martin, made from a pair of spectacles with Reticello glass lenses. The spectacles frames were found by Charlotte at a flea market in Amsterdam, which she then created a pair of Reticello lens to fit them. Reticello is a traditional Venetian technique where glass blowers create the lattice pattern by employing glass rods that incorporate colour which they gather onto the blowing iron and then blow into forms or spin out into discs.

Ironically the most fragile part of the spectacles – the Reticello glass lenses – remained intact but had fallen out of the broken frame. The frames, which had evidently already lived another life or two, were broken in four parts. The two temple pieces were broken off from the bridge and the metal frame was also fractured.

The main part of the frame is made of type of plastic – celluloid. A look under a high magnification microscope was enough to identify the material. Celluloids are a class of compounds created from nitrocellulose and camphor, with added dyes and other agents. First invented in the mid 19th century, it was marketed as an imitation of ivory, tortoise shell and horn. Unfortunately, early plastics are subject to inherent and inevitable deterioration, and our object wasn’t an exception. It was showing signs of chemical deterioration, which included weeping and crazing, which very likely contributed to the corrosion processes on the metal parts.

Cellulose nitrate degrades to produce acidic and oxidizing nitrogen oxide gases including nitrous oxide, nitric oxide and nitrogen dioxide. All of which could affect and catalyze the degradation process of other materials, such as metal corrosion.

There was also an old join and previous surface treatment which now was degrading the coating.

The frame fixings at both temples were not flexible, and seemed to be locked into a closed position, which prevented the temples from opening and closing. Initially I assumed this could be part of the original intention of the artist, but after consulting with her I learnt that ‘they weren’t ever supposed to be worn, though I have worn them once!’. So, if the artist had worn them, then they were meant to be mobile, and they were just jammed by the buildup of corrosion and some soiling.

The metal bridge remained complete and still held a small section, though it was detached from the rest of the frame. The metal wires which were supporting the glass lenses were fractured in several areas and there was also some copper oxidation visible at the areas where the metal joins plastic.

The two metal fixings which were locked into a position regained mobility after cleaning off the corrosion and soiling using cotton swabs and solvents. A minor amount of Microcrystalline wax was applied to the metal fixings to keep them mobile and flexible.

The most challenging aspect was the reconstruction and re-adhering of the plastic frame, which I had to do in stages, using a type of epoxy resin. The nature of the damage caused the plastic to slightly deform. Also some of the joins had minor material losses which prevented the joins from aligning perfectly. I used fine – but strong – Berna clamps to hold the bonded sections together, and to support the joins while the adhesive cured.

Every conservator would agree that it is not easy to adhere plastic to plastic. In this case, I had the advantage of being able to use the original metal wire holding the glass lenses as an armature to support the plastic frame and act as an additional support. The detached metal wires were adhered to the inner side of the plastic frame also using the same epoxy resin.

Finally, the glass lenses were fitted within the metal wire frames and adhered together using the same epoxy resin as above. Due to the multiple fractures the metal wire also was deformed and sprang out which caused slight misalignment and tension in some of the joins.

It didn’t help that the lenses originally never fitted very well within the frames in the first place. Due to the awkward shape and difficult joins I had to devise my own “clamp”, using U-shaped steel metal wires inserted within a Plastazote block and adjusting these by simply twisting the two ends of the wires at the bottom. This also helped when reconfiguring and tightening the stubborn final joins. Good old tape was also used as an additional support while the adhesive was curing.

Fragment by fragment the spectacles were restored as far as possible to its original state with the full collaboration of the artist.

Museum collections including art, design, fashion and historical pieces, include objects made from early plastics. Conservators all around the globe are faced with the challenge of conserving and preserving plastics. The degradation of plastics is ongoing and unfortunately none of the current studies provide us with a clear answer on how, and if it is possible, to stop this. However, today’s conservation methods could provide preventive measures to slow down the degradation process, such as low temperatures/cold storage and low relative humidity, as well as isolation form other materials that may be affected by the fumes released during its break down.

As a preventive measure the spectacles were packed separately to avoid contact with other objects and placed within a controlled environment, where its condition and further degradation can be regularly monitored.

How to fix a broken leg

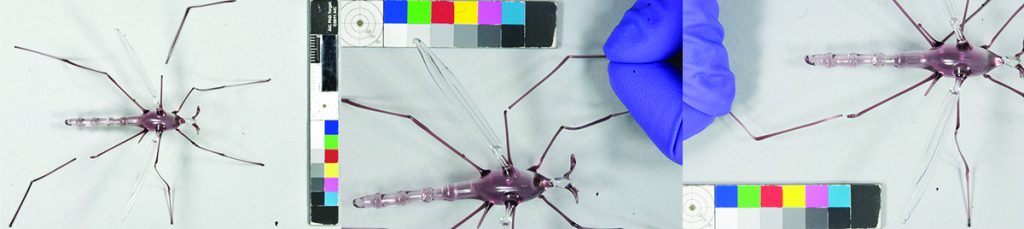

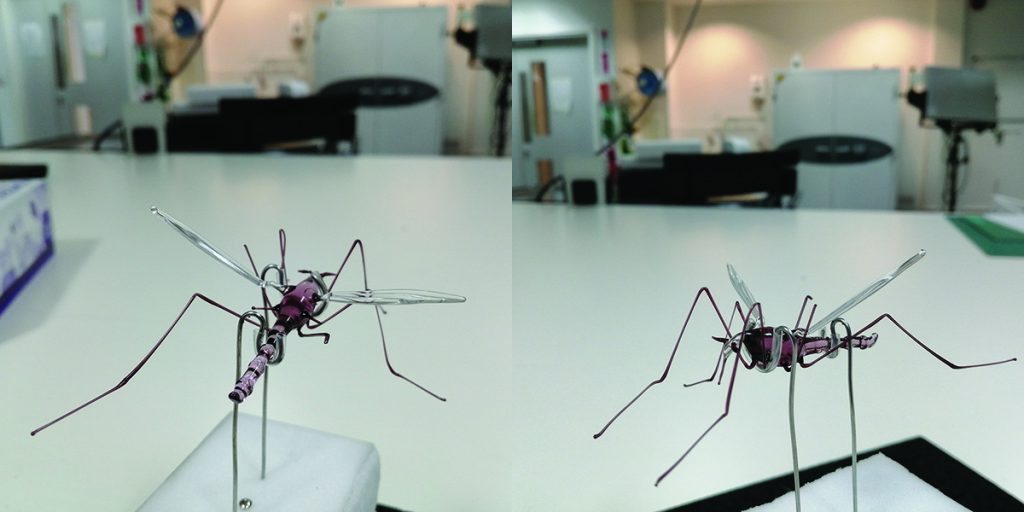

Another object I enjoyed conserving was a figure of a lampworked Crane fly by David M. Beard. Lampworking is a glass technique that involves the artist melting glass rods over an open flame or burner, which they then manipulate the molten glass with tools, and can inject air into the forms they are creating via a mouth tube.

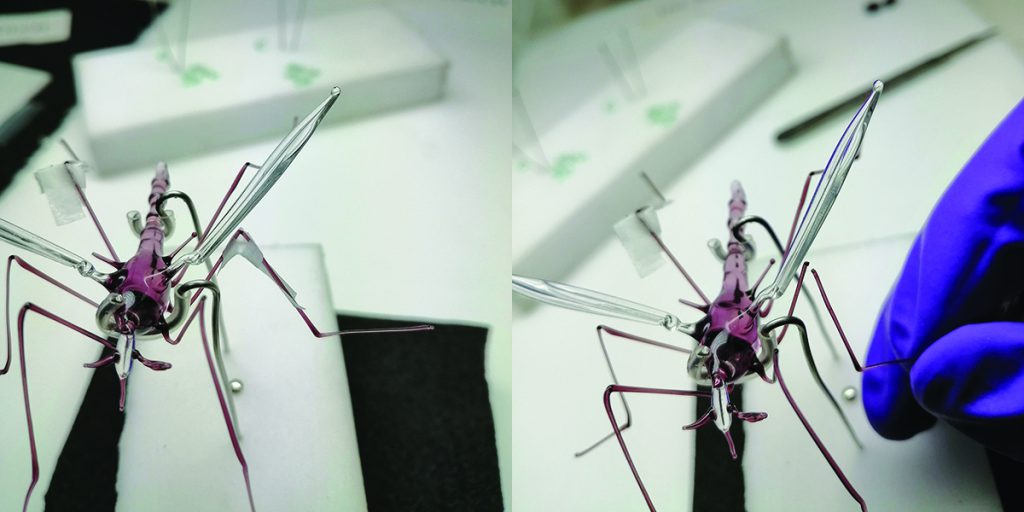

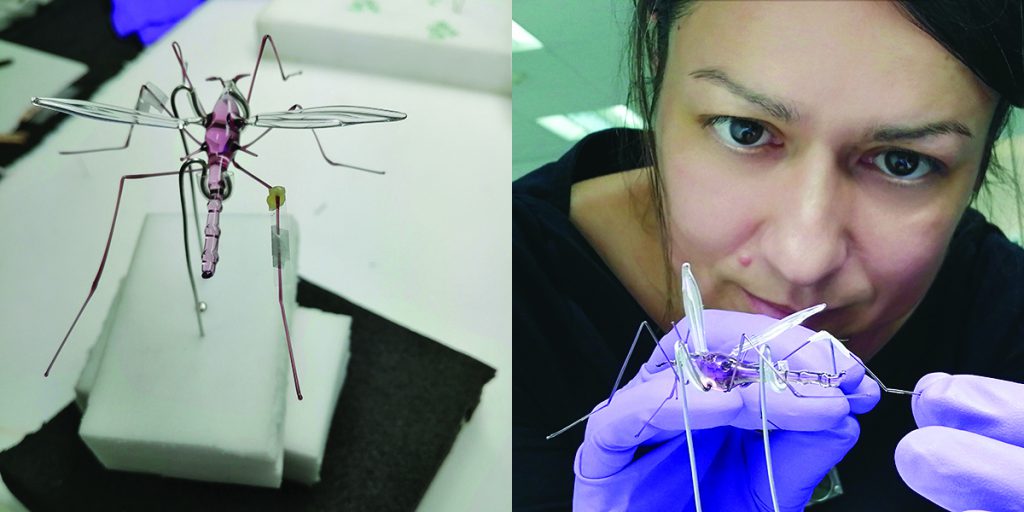

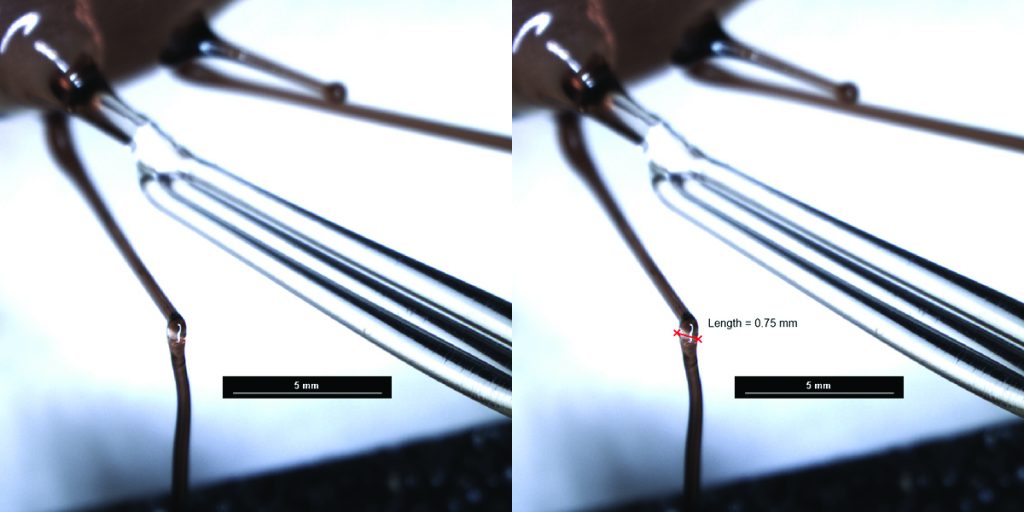

The challenge here was not only the extremely delicate and fragile nature of the artwork, but also the object miniature size – 9 cm length, with legs that were less than 1 mm thickness! The Crane fly figure had two legs damaged – the middle left leg proper and back right leg proper, as you can see at the photos below:

Due to the small size of the artwork I devised a temporary mounting solution to support the object so I could easily manoeuvre it while conserving it. I made the little mount simply by bending a steel wire and inserting it into a dense Plastasote block. I covered the wires with silicone surgical tubing (a cool trick I’ve learnt from professional mount-makers) to avoid the metal touching or scratching the glass.

Unfortunately, the legs had lost some material, so the join was very hard to align perfectly. The middle left leg was re-adhered using HXTAL epoxy resin. The join was supported during curing using a sling-like support made out of Melinex sheet, sticky wax and again trusty old tape. A very similar support was used to support the back leg while the same kind epoxy resin was curing.

Due to the extremely thin join, I had to use a very small Japanese tissue paper strip – less than a millimetre, was applied across the join at the back leg for additional support.

Finally, the temporary mount I described in the beginning did not go to waste. I decided to incorporate it in the packing method, so it could hold the object into safe and accessible position while in storage or transit.

Image © National Museums Scotland

During this project, having the opportunity to communicate directly and collaborate with the artists while conserving their artwork was an invaluable experience for us all. These exchanges allowed us to share our knowledge around different materials, that then led us to take our conservation skills to another level. This encouraged us to develop new techniques and to find solutions when it looked like there was none – leading to inspiring inter-specialism collaboration across different museum departments, as well as external institutions and the artists.

I am so proud of my team of conservators and what they have achieved, and to have had the experience myself to take part in such a unique project. My thanks go out to them, the artists involved, and also Sarah Rothwell, who was our inspirational source and the life-link to the artists and their artworks.