Making a colour digital recreation of a 14th-century sculpture, where almost none of the original paint scheme has survived, is challenging. Not only are we working with a very small amount of evidence, but achieving the subtleties of hue and tone mastered by an artist with a brush 600 years ago, today on a screen, is quite frankly, impossible. We will never know exactly how it looked. Having said that, we are fortunate today that we have the technological know-how to bring to life an impression of that original appearance and this aim drove this second phase of our Umbrian Madonna project.

It has been four years since the new Art & Design galleries opened at the National Museum of Scotland, when a painted wooden 14th-century Italian statue known as the Umbrian Madonna and Child went on display for the first time in many decades.

Since 2015 we have conserved hundreds of objects for three more new galleries and two newly refurbished ones, as well as supporting the museum’s temporary exhibition and loans programmes. During all this, however, I have been fortunate in being able to continue overseeing our Madonna project which we have blogged about in the past. Thanks to additional funding from the Henry Moore Foundation and the KT Wiedemann Foundation, we have now been able to create a 3D digital colour reconstruction.

This is the story of how this was done…

First we approached paint expert Mark Richter at Glasgow University to remove 15 tiny fragments of paint no bigger than a pencil tip, using a scalpel

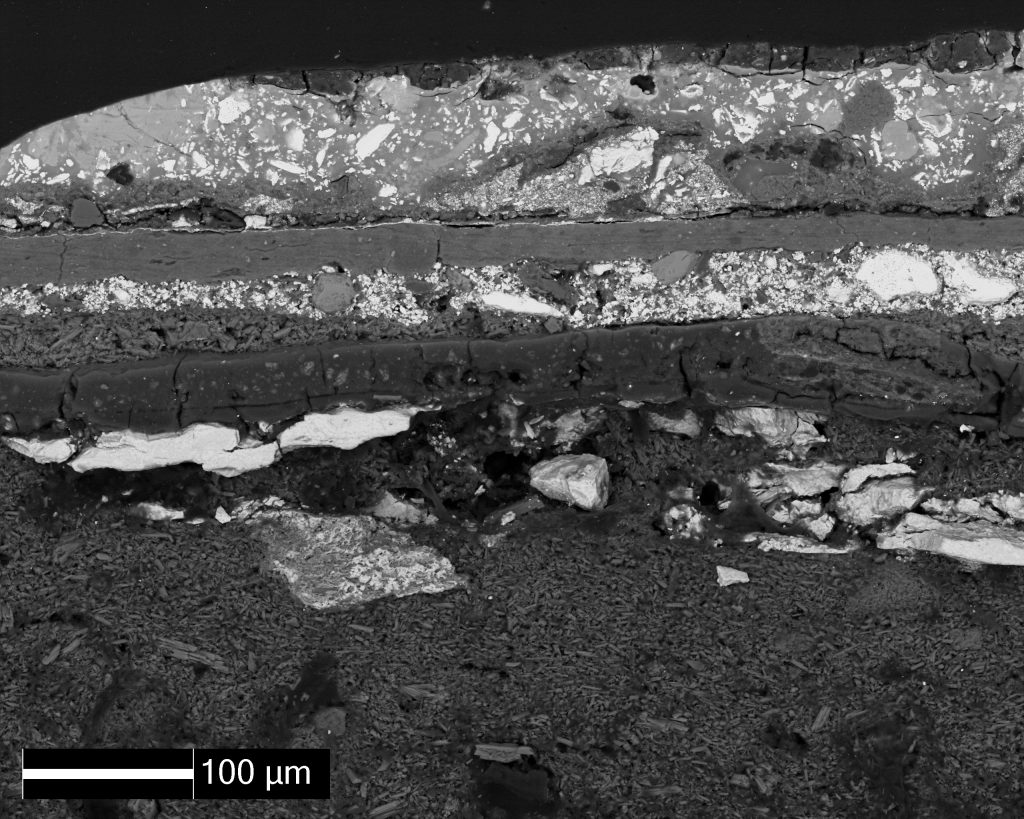

After these samples were mounted and polished in resin blocks so that a cross-section of paint layers could been seen, we called upon Lore Troalen, our Analytical Scientist, to analyse the samples to determine the pigments and binders found there a Scanning Electron Microscope, UV imaging and Fourier-transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR).

Highly magnified image of a paint cross section under ambient light.

Under a scanning electron microscope (SEM).

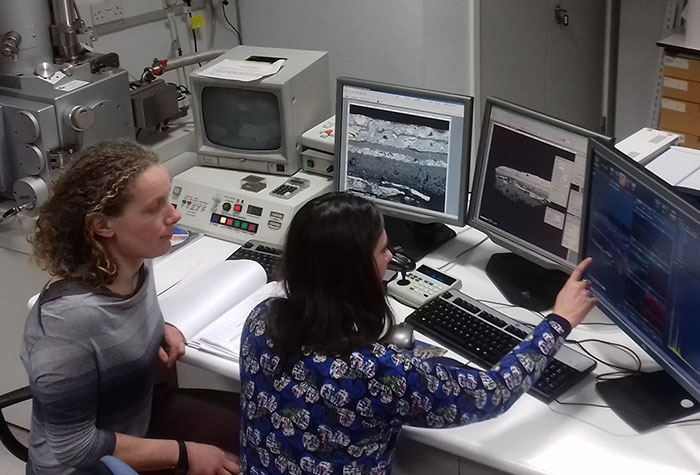

Lore Troalen and myself discussing the SEM data.

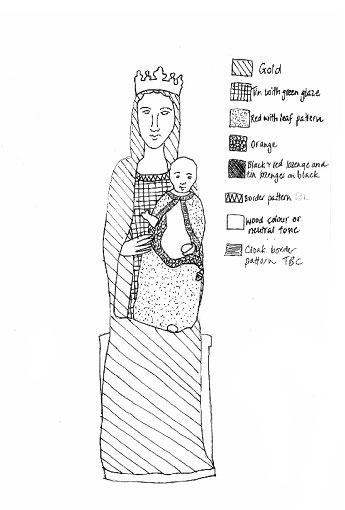

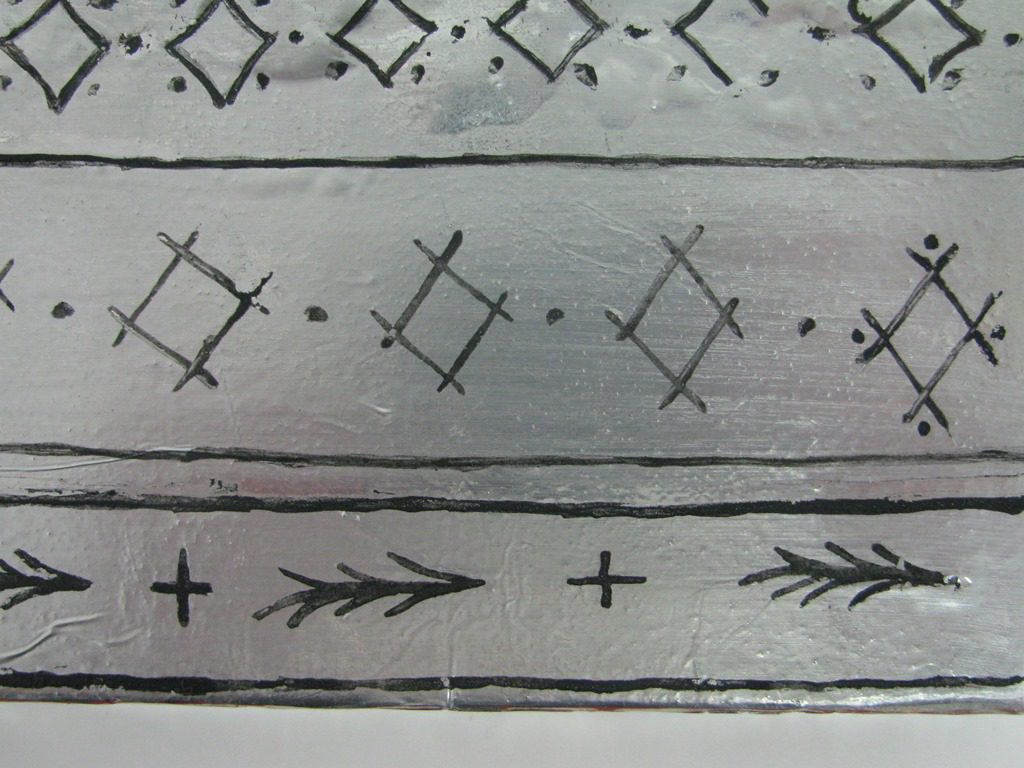

Next we matched the samples together, also studying the surface the sculpture in minute detail for more clues to establish which layers in the cross-section represent the earliest colour scheme on the sculpture. This close surface study helped us identify areas where original patterning was exposed, for example on the Christ Child’s cloak, and lozenges on the sides of the throne.

Decorative details noted on the sculpture.

Decorative details noted on the sculpture.

Although the cross-sections and surface study reveal a lot, creating a full colour reconstruction from these tiny clues is difficult and it was important to solicit the views of others. We are fortunate to have an expert in early Medieval sculpture here at the museum, Xavier Dectot, Keeper of Art & Design, and also Helen Wyld, Senior Curator of Historic Textiles. We needed to put our findings in context and as there are almost no polychrome sculptures with original polychromy surviving and certainly not in Scotland, we went to the best source of comparative 14th-century costume, namely panel painting. Helen Wyld sought to find paintings where similar colour palettes had been used or where similar brocade border patterns had been employed.

Knowing that the outcome could only ever be a best guess, we then agreed on a colour scheme for our sculpture. We agreed that we would keep it simple – though the original may well have been more ornate – so that we were sticking as closely as possible to our evidence.

I then worked with a technical art history student from Glasgow University, Jennifer Anstey, to create a set of sample boards. These were painted out using medieval recipes and techniques combined with the scientific data gathered on the pigments which were observed on the sculpture. This gave us a reference of paint samples and patterns to work with for the digital reconstruction.

Tools required for mixing egg tempera paint.

Pestle and mortar using for grinding Verdigris for the Virgin’s tunic

The following stage was to enlist Jared Benjamin and Sam Ramsay from Glasgow School of Simulation and Visualisation (SimVis). We provided them with the sample boards, which they photographed, and also with schematic drawings. We agreed that we would leave wood-coloured the areas for which we did not have enough data to be able to make an informed guess about. Equally, for the skin tones, where recreating the subtleties of a textured tonal painted surface would be particularly difficult, we decided to leave wood-coloured.

Sample patter for the border of the Virgin’s cloak.

Sample pattern for the side of the throne.

Sample pattern for Child’s cloak.

We also provided SimVis with a model created by Tom Challands of Edinburgh University, rendered from CT data taken during the first phase of the project. This showed the construction of the wooden elements of which the sculpture is comprised. We asked them to combine this with their colour recreation so that the viewer could get an idea of the sequence of events in production:

First the wooden elements are assembled and nailed into place. Then the whole sculpture is coated in ‘gesso’, a white preparation layer made of gypsum and rabbit skin glue, then finally the gilding and paint is applied, including the decorative brocade designs.

The animation was produced with an explanatory text to go with it, and our Digital team produced a voice-over to run with it.

In conclusion, years of repainting and wear mean that the original appearance of our piece is lost: the viewer in the gallery can appreciate the sculptural form, but cannot experience the richly vibrant appearance our sculpture once had. We have gathered a mass of data which will be of use for future research purposes, adding to a body of knowledge on materials and techniques from 14th-century Italy. Rather than keeping that information within the academic world, being able to translate it into something available to everyone was one of our key project goals so we are delighted to have been able to realise it with this animation.

The Umbrian Madonna and Child as it is today.

The colour rendered reconstruction.

You can find out more about the sculpture at www.nms.ac.uk/madonna.

The project is supported by the Henry Moore Foundation.