During my placement with the Artefacts team, I was given an exciting and challenging opportunity to treat a piece of modern glass.

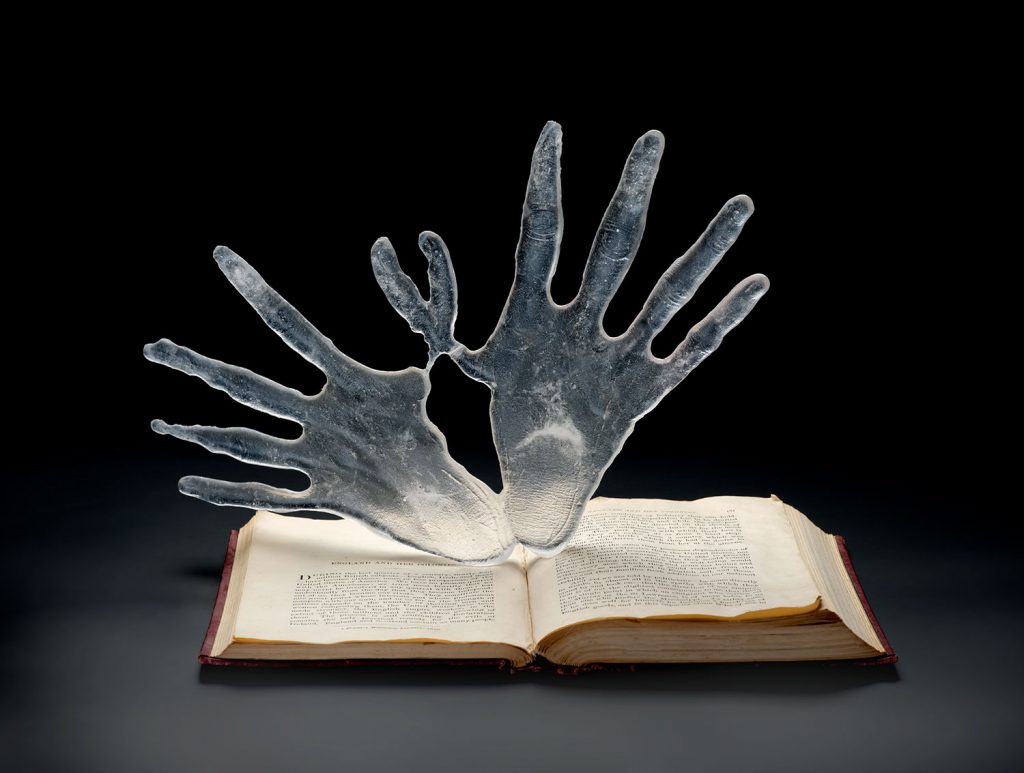

‘Form’ is a piece designed by artist Deborah Hopkins, whose works often combine glass with other material to explore expressions of human body parts. The piece was purchased by glass collectors Dan Klein and Alan J. Poole. In 2009 a selection of the collection was generously donated to the National Museums Scotland, and many pieces can be seen displayed in the Making and Creating gallery.

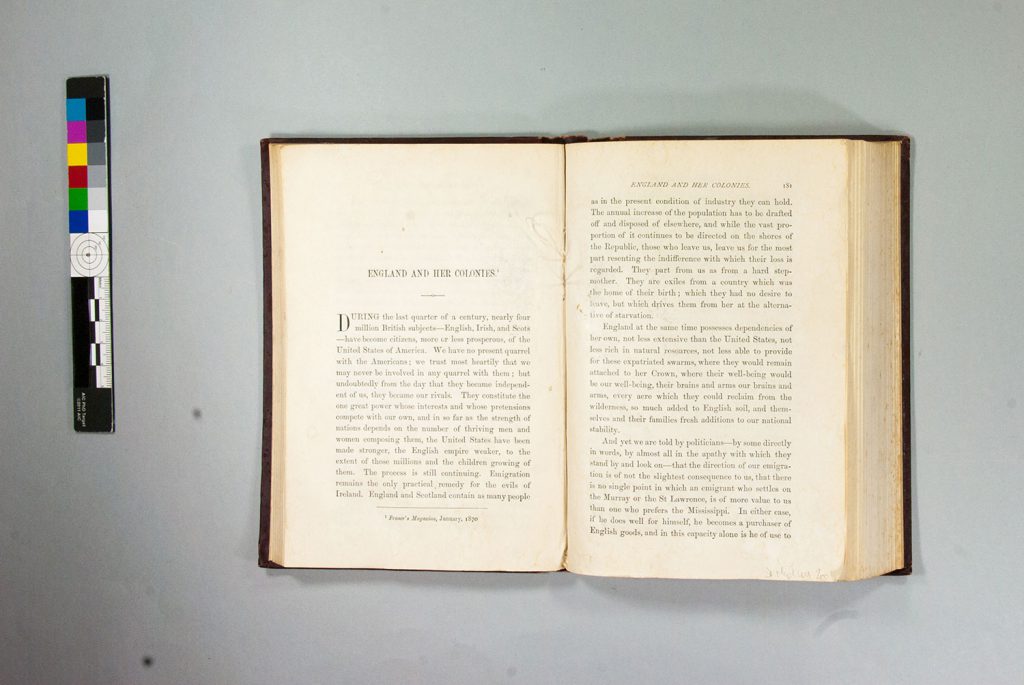

‘Form’ is comprised of cast glass hands interlinked at the thumbs and mounted on a cloth-bound book. The interlinked thumbs had unfortunately suffered impact damage when the mount failed, causing the thumbs section of the glass to be broken. The aim of the treatment was to stabilise the object and reattach the thumbs, as well as devising a new, more stable mounting solution.

Conservation challenges

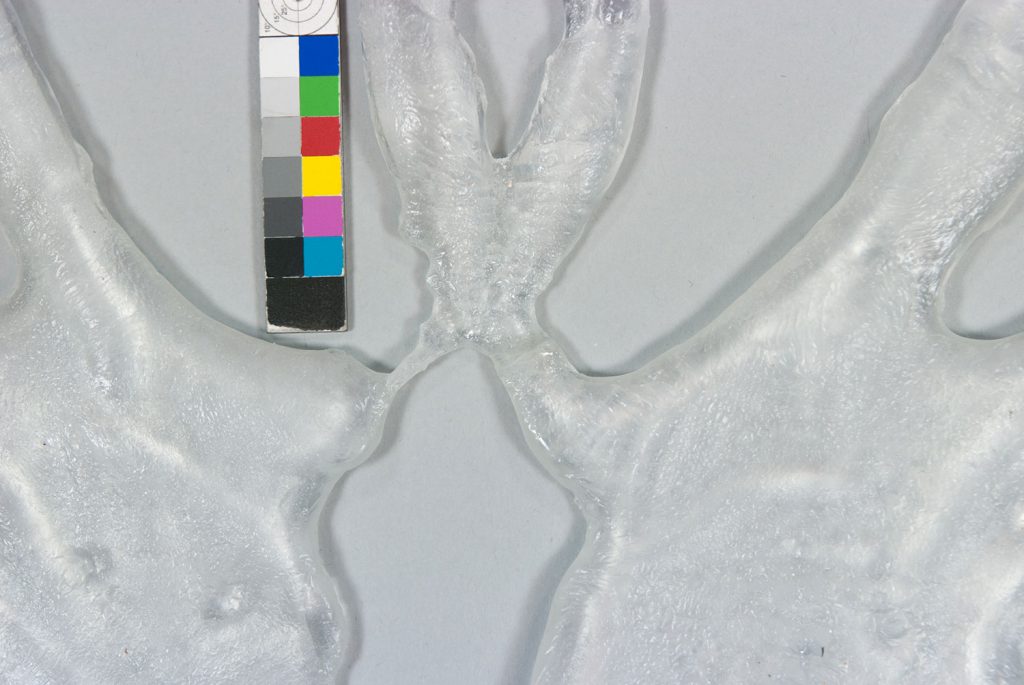

Although I was keen to get started and treat the glass hands, there were significant conservation challenges that needed to be carefully considered. The crossed thumbs had been broken from the hands with only a small area of contact for the reattachment. It was therefore going to be a challenge for me to bond the thumb and hand section correctly. Alignment of the broken section onto the main body of the hands would also be challenging as the glass is three dimensional and not flat. There was an area of loss connecting the thumb and hand sections which would be crucial to stabilise the piece. And of course I would need to ensure the treatment was sympathetic to the transparent nature of the glass and not visually jarring.

Treatment

I assessed the object and formulated a treatment plan with my supervisor, Stefka Bargazova, to ensure I was treating this complex and mixed-media object in the most appropriate and effective way. I cleaned the surface of the glass with a solvent and deionised water mixture and degreased the break edges. After some consideration I decided to use an epoxy resin to bond the sections.

The visual impression of a crack relates to the refractive index of the material within the crack relative to the refractive index of the glass. Refractive index determines how light will behave when it passes through a material. In practice, this means if the refractive index of the adhesive and glass are a good match, the crack will be less visible. The refractive index of epoxy and modern glass tend to be close and therefore I selected it as an appropriate material to bond the glass.

Conservation grade epoxy has little viscosity and therefore tends to spread from the point of application, so I was concerned this could lead to damage to the hands. To discourage this, I placed the piece on a cutting mat and cut a channel into the mat where the bond line would be. Without this channel, the applied epoxy could travel through the piece, and the excess could potentially spread across the back of the object. Using this technique, the adhesive is encouraged to drip downwards into the channel and not spread across the object.

Achieving the crucial correct alignment between the thumb section and hands was tricky. I achieved it by using a series of paper wedges to produce the correct level. I used a technique of small dots of melted sticky wax to temporarily secure the thumbs into place. The epoxy was applied via capillary action to the bond line and left to cure. Finally, the sections were back together and no adhesive had spread – a great result!

I considered two options to stabilise the area of loss between the thumb and left hand. The first was to cast and cut a sheet of Paraloid B-72, an acrylic resin, to match the area of loss and tack it into place with further Paraloid B-72. This would offer some stability and a transparent support which would be a good match for the glass.

Alternatively, a sheet of Japanese paper impregnated with epoxy could be applied to the area of loss. This could be moulded more effectively to match the curves of the piece and would offer good stability. Using the paper as a mould, the loss could then be filled using epoxy bulked to make a paste, which would further stabilise the piece. The glass hands are slightly opaque and therefore the impregnated paper would not be too visually jarring. I assessed both options fully and selected the second due to the better stability offered by the paper and epoxy combination.

The fill to stabilise the detached thumb and hand section was done in two stages. First I applied the strip of impregnated Japanese paper across the missing area on one side and then, after curing, the hands were turned over, and the area of loss filled with gelled epoxy and a further strip applied and shaped to match the original break edges. I also filled a second area of loss associated with the break at the right thumb with the paste to provide additional stability to the join.

I was pleased with the outcome achieved: the thumb section was reattached to the main hand section successfully and the areas of loss filled. With a treatment of the glass hands complete, I and the artefacts team, along with the artist and curator, were able to consider together options for supporting the hands to stand on the open book.

Displaying the piece

It was fascinating to be able to establish communication with the artist herself to discuss the original display, as I was not clear how it would be physically possible to stand the hands upright on top of an open book.

The artist solved the mystery by describing her original and very creative method of mounting: a piece of fishing wire is threaded through the spine of the book and tied around the part where the hands join. The tie is hidden in the book spine. Pulling the wire taut allows the hands to be held in place. The placement of the wire around the thumbs was now to be on the restored area and therefore it was concluded the original display method was no longer safe for the object. A custom-made mound could be devised to discretely imitate the original, to provide further stability and support for the object.

The idea for the custom-made mount is to imitate the original mount, but provide stability and support, so the object would not lay on its own weight.

Form, cast glass hands mounted on a cloth bound book by Deborah Hopkins, 2004, (K.2011.60.141). Donation from the Dan Klein & Alan J. Poole Collection.

Moving on

Tackling this complex glass project has allowed me to consider and practise support and bonding options. Since completing my placement, I have been working within a private conservation practice where I am currently treating a Lalique mermaid. This piece is a 3D object with challenging alignment issues. Working on ‘Form’ with the support and guidance of the Artefacts team has allowed me to be much more confident in my approach with the Lalique glass and achieve a better outcome on the treatment.