For three years I have been participating in a research project funded by the National Science Foundation in the USA.

The Norse Use of Marine Mammals in the North Atlantic is led by Dr Vicki Szabo of Western Carolina University and involves research collaborators from the USA to Denmark. The aim is to look at which marine mammals were exploited by Norse peoples during the Middle Ages (c.800 – 1500 AD) by analysing the remains of past meals and worked bone in houses, farms and waste dumps in Canada, Greenland, Iceland, Orkney and Shetland.

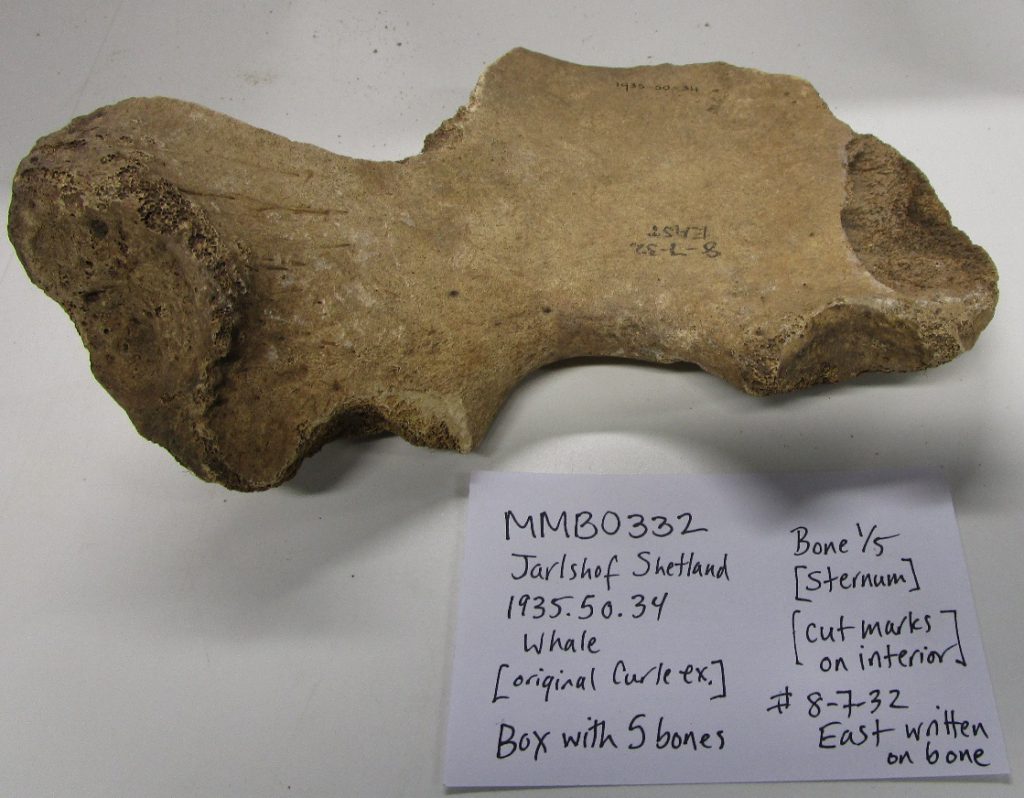

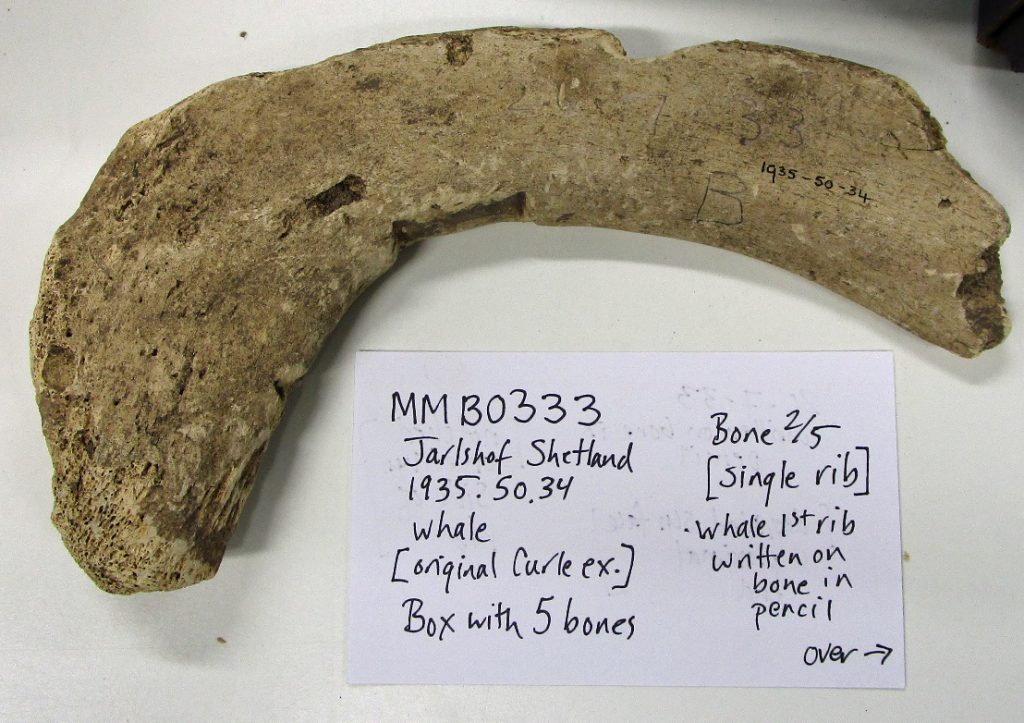

The problem with the remains of whales in these sites is that they are often just fragments of bone. We know they are whales, but not which species, because the pieces are too small. Therefore, the bones are being analysed in two ways. Firstly by extracting ancient DNA to compare with DNA from modern whales; and secondly by extracting collagen, a structural protein found widely in animal bodies, from the same bone for comparison with collagen from modern whales.

In the event, collagen identifications were twice as successful as ancient DNA ones, but they are less specific and often cannot distinguish between closely related species. A great surprise was the identification of a grey whale, a species long extinct in the Atlantic, from a bone fragment from Orkney – the first record from Scotland.

After analysing over 300 bony samples, we met at the end of May at the Duke University Marine Lab in Beaufort, North Carolina, to discuss our results and see what further research would be required.

Not surprisingly, the different sites across the North Atlantic yielded different marine mammals depending on what species were locally available; seals predominated in Greenland and Canada, whereas toothed whales were more common in Orkney.

The biggest surprise was in Iceland, where the remains of blue whales, the largest animal that has ever lived, were by far the commonest bony remains. Blue whales have been over-exploited in all the world’s oceans and numbers are very low today in the North Atlantic, perhaps less than 2,000. No doubt blue whales were much more abundant in Norse times, but since modern exploitation began in 1860, numbers plummeted and have only been slowly recovering in the last 60 years since hunting was banned. However, it didn’t seem to make sense that blue whales would be superabundant in northern Iceland, so that they stranded so frequently to be exploited so much.

Another important strand of the project has been to investigate and translate old Icelandic accounts, which often make mention of the diversity and exploitation of marine mammals. These ancient texts have revealed that blue whales were actually hunted in Iceland during Norse times and whales were key to the survival of the people in these poor agricultural areas.

Although landowners were entitled to a share of any whale that stranded on particular stretches of coastline, there were strict rules governing how the whales would be shared out among neighbours. Blue whales may have been actively hunted by stabbing them with a lance and leaving them to die. After a long wait, the whale would turn up stranded onshore to be exploited by all.

What is interesting about these historical accounts is the knowledge of the different species of whale, but also which should and should not be exploited for human benefit. This project has shown that whales were much more important to early peoples than previously realised and that exploitation of rorquals, the group to which blue whales belong, began much earlier than was thought possible. Previously it was thought that only right whales and bowhead whales were hunted actively because these species float when killed, whereas the rorquals sink. Only when a method of inflating the carcasses with air was developed were these huge animals available to industrial hunting.

Our research has challenged this assumption and we now need to look at how Norse exploitation of blue whales may have impacted negatively on North Atlantic blue whales far earlier than realised, which may also explain why their recovery has been so slow since the late 20th century.