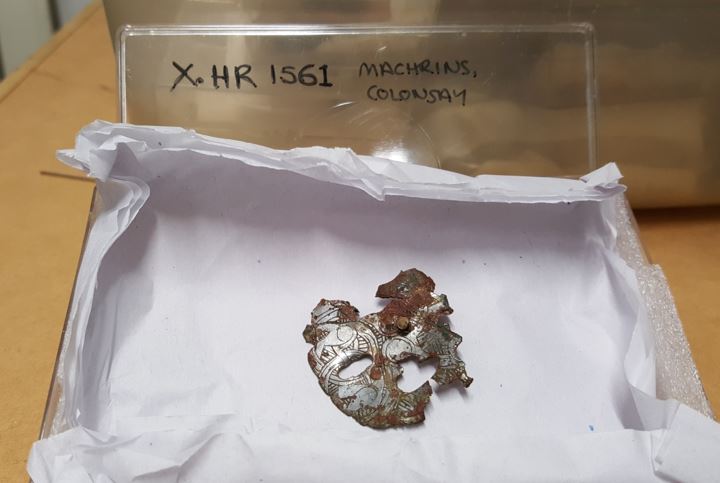

The small jewel case was marked Machrins, the name of a Viking cemetery on Colonsay, so it immediately caught my attention. I unwrapped the tissue paper to reveal a shining fragment of metal with curious markings on it.

On closer look, the ornament reminded me of the intertwined beasts with hatched bodies on the St Ninian’s Isle, Shetland silver mounts. It looked silvery, but its fragmentary condition meant I wasn’t sure exactly what I was looking at.

On further research, it turns out the item I stumbled upon in storage was one of only two known fragments of an Insular decorated bucket from Scotland. These are rare prestige items of the 8th century. There are only about twenty known from Ireland and another dozen or so from Scandinavia. The Irish examples have been found in settlement contexts, or deposited in watery places like bogs and rivers. The Scandinavian examples have mostly been found in Viking graves, as were the two from Scotland.

(Photo: Ole Bjørn Pedersen, NTNU Vitenskapsmuseet T20913:3)

(Photo: Universitetsmuseet i Bergen B4511)

Right: Insular bucket from Oseberg, Tønsberg, Norway.

(Photo: Kulturhistorisk museum, Oslo C55000)

These decorated buckets were part of the material culture of power in Scotland at the time of the first Viking raids.

The word ‘bucket’ doesn’t scream out luxury goods now, but they require a combination of the expertise of several craftspeople to assemble them, from the tricky process of carving yew, to the carpentry techniques used to create a watertight vessel, to the fine decoration of sheet bronze riveted to the outer face, and the crafting of an escutcheon which is strong enough to hold a bucket full of liquid yet often carries much of the symbolic protective communication of the vessel’s ornament.

It is difficult to tell whether they were intended for feasting or ecclesiastical rituals, because like the items of the St Ninian’s Isle silver hoard, they blend secular and religious imagery. ‘Power’ in that time meant the ability to appeal to worldly and otherworldly forces.

This is perhaps why they were targeted by the earliest Viking raids. We know this because many of them are found in 9th-century graves in western Norway. In a time when Insular metalwork was so often cut up or melted down for reuse, the buckets seem to have been singled out for special treatment, as several of them survive intact. The best examples are from richly furnished female graves at Skei, Hopperstad and Oseberg. The decoration and form of construction shows that some of these buckets were almost certainly made by the same workshop.

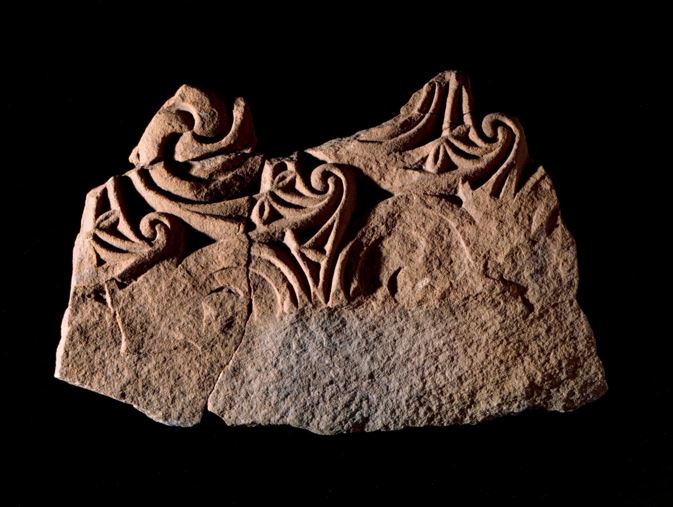

The use of patterns like inhabited vine scroll and trumpet scroll, ornament foreign to Scandinavia, allows us to place them more closely. The diagonal fret patterns from Skei are matched on Irish metalwork like the Bangor, Co. Down bronze handbell. However, inhabited vine scroll is rare in the sculpture and metalwork of early medieval Ireland.

We now have several examples of all these motifs in metal and stone from Scotland. The Northumbrian high crosses of Hoddom and Ruthwell in Dumfriesshire show a mastery of plant scrolls and interlaced animals, which also appear in metalwork like the Dumfriesshire mounts and the Rerrick plaque. But there is no evidence for the use of trumpet scroll on Northumbrian material culture. On the other hand, Pictish cross slabs in the northeast excel at such patterns, as shown particularly in the sculpture of Easter Ross, such as the Hilton of Cadboll stone.

Thanks to the excavations at Portmahomack, we now have evidence that deluxe items in stone and metal incorporating trumpet scroll, vine scroll, and fret patterns were being made by the workshops of this monastery. Portmahomack also happens to have the clearest evidence for a Viking raid of any of the northern monasteries excavated so far.

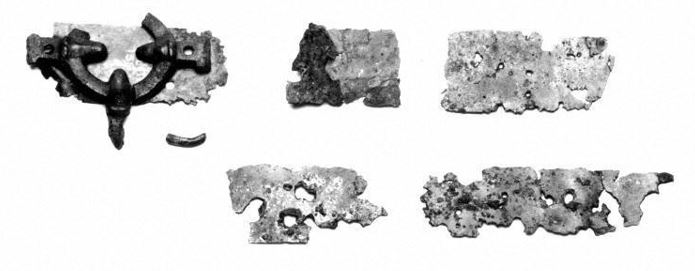

Two insular decorated buckets from Scotland

Despite all this, the bulk of the evidence for the use and production of decorated buckets is still in Ireland. But it is important to say that, as some art historians have long argued, it is at least as likely that Insular decorated buckets were manufactured in a Pictish context as an Irish one, and regardless they all belong to a shared Insular aesthetic which is actively cutting across these disparate areas in the name of the Church.

We can take a closer look at the two Scottish bucket fragments. The Machrins, Colonsay fragment admittedly does not look much like a bucket now, as it seems to be a piece of the decorated bronze sheeting from one which has been cut down for reuse. The style of the animals is closest to the conical mounts from St Ninian’s Isle. There are holes punched through the ornament for the domed stud that was found alongside it. The Vikings were keen at ‘upcycling’ Insular items like these; in a previous blog I mentioned the reuse of shrine mounts for brooches in a Viking grave on Oronsay. A grave nearby also contained a ringed pin of Insular type, possibly from a female burial.

The other bucket fragment was also found in a Viking grave on the Hebridean island of Eigg. It is one of several items found in the 19th century near the early medieval church of Kildonnan, representing a small but important Viking cemetery. There is rather more surviving of this bucket, with its distinctive cruciform escutcheon, the mount from which the handle was suspended, currently on display in our Early People gallery in the National Museum of Scotland. Not on display are more fragments of the bronze sheet which would have bound the rest of the bucket. It is thus more likely that our fragments are from a bucket deposited intact in the grave like those in Scandinavia, but we have no other information about its context.

What were the buckets used for?

The majority of surviving examples are made of yew wood. Yew carvers had the highest status among early medieval Irish woodworkers, and despite its potential toxic qualities, it was the most favoured wood among surviving vessels from Ireland and common in Anglo-Saxon contexts as well. Decorated buckets have been used in elite graves since the Iron Age, with several examples known from 6th and 7th century Anglo-Saxon graves, including the famous ship burial at Sutton Hoo.

The particular 8th-century series of decorated buckets found in Ireland, Scotland and Scandinavia are linked by their use of Christian imagery, including cross-shaped ornaments on the escutcheons and inhabited vine scroll. It has been suggested using later medieval parallels that they were used for carrying holy water, perhaps for baptismal rites or liturgical purposes. The ones in Skei and Oseberg were found with bronze ladles, so it may be that these were used (or repurposed) as a ‘set’ of feasting gear. We have a bronze ladle from a female grave from Ballinaby, Islay showing they may have had some kind of symbolic resonance on their own, whether they were actually used for feasting or not.

Like the Scandinavian examples, the decorated buckets seem to be deposited in powerful places. Machrins and Kildonan are two of only a handful of sites in Scotland which have a cemetery of pagan Viking graves, rather than just a single grave. The Eigg graves are next to a church we know was in existence since at least the 7th century. One of these graves produced what is perhaps the most elaborate sword hilt from any Viking grave in Britain. Perhaps the inclusion of Christian material and an association with the church is one of many ways in which power was projected.

Our two buckets are only scraps today but have opened up a world of big stories about this period for me. What we call Viking graves in Scotland are assemblages of material gathered from Britain to the Baltic and beyond, and the act of gathering and acquiring prestige materials from faraway lands may have been a powerful message in itself. They are the marker of new arrivals, whether into a new land or a new status. And as martial as our image of the Vikings may be, much of the looted wealth is made visible through female graves, who did not always need to be warriors to have power. The role of women in the age of raids has yet to be addressed adequately.

Many questions remain, but the journey from a scrap of bronze to these big stories is the power the material retains today.