I had just moved to Edinburgh to begin my conservation internship with National Museums Scotland when I was tasked with preparing the Thomas Glen Victorian Highland Bagpipe for the exhibition Wild and Majestic: Romantic Visions of Scotland.

As this was my first time ever in Scotland , having such a distinctly Scottish object as my first project really set the tone of this final phase of my education towards becoming an object conservator.

The bagpipe would have originally been a highly decorative, ornate example of this type of instrument intended for military display, but upon arrival at my work bench, it seemed lacklustre from years of disuse.

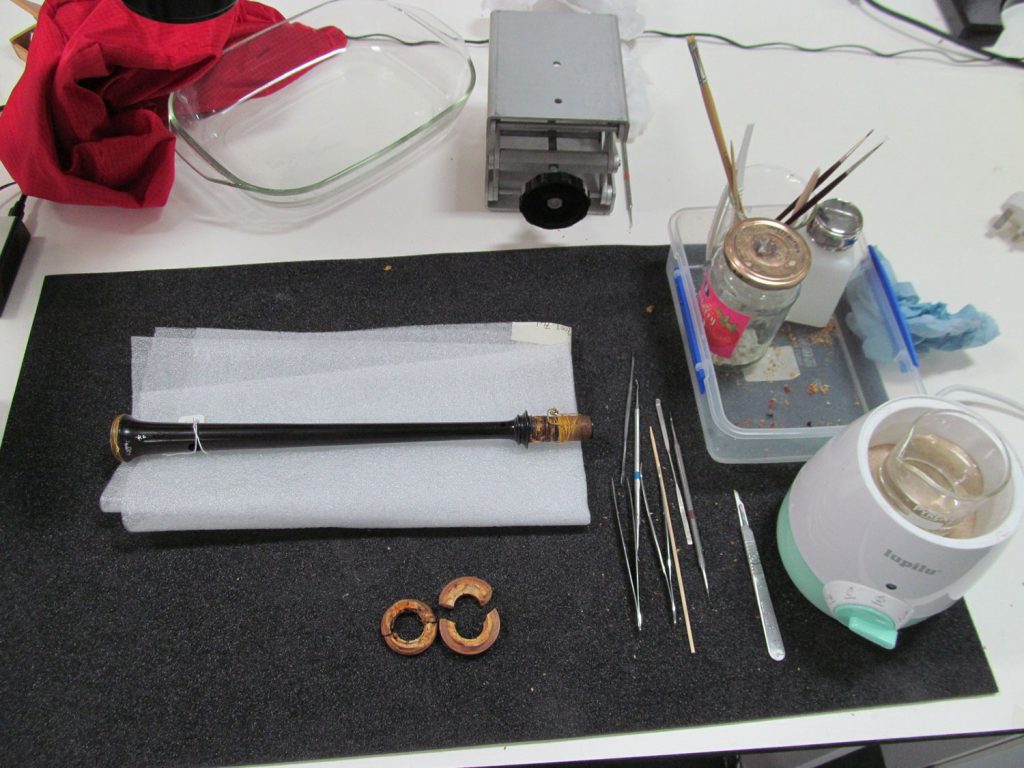

Old animal glue was removed from the fragmented chanter bone mount until all the pieces were free to be reconstructed with a better fit.

One of the cracked bone fragments was rehumidified so the bone swelled and closed up the crack. It was then secured with fish glue, which has similar environmental responses as the bone. This allowed the bone to ‘breathe’ without constraining it as a synthetic adhesive would have done.

An acrylic adhesive was used to reconstruct the pieces on the chanter, as this would not dry and shrink like the animal glue. This adhesive was also mixed with wood flour to create a putty to fill in gaps.

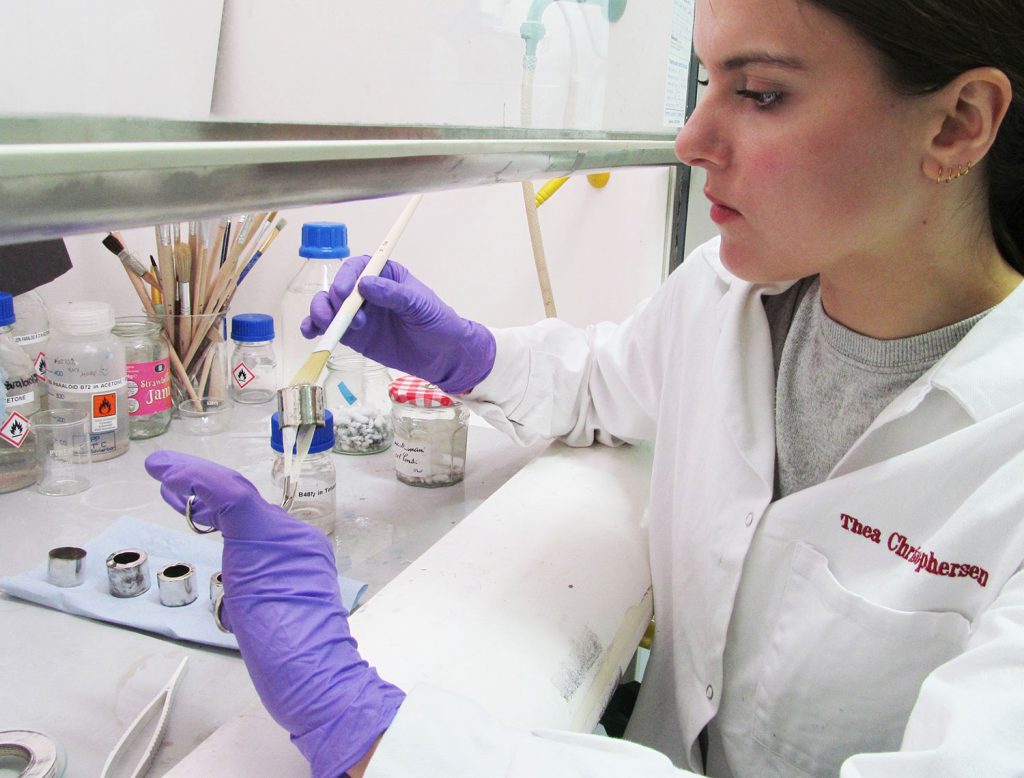

The silver ferrules (fastenings), chanter sole and other silver embellishments on the drones were degreased by swabbing with IDA, acetone and white spirit, and polished with an aluminium oxide polish with a drop of detergent.

After the tarnish was removed, the silver was cleaned of polish residues by swabbing with solvents, then lacquered with an acrylic.

The ferrules were secured to the drones and the sole to the chanter with an acrylic adhesive, adding a bit of Japanese paper to the sole to tighten the grip.

As a final step, the Royal Stewart tartan cover was sent to Textile Conservation for a cleaning. Afterwards, the bagpipe was structurally sound and shining bright, ready for display!

You can see the bagpipe in all its glory in the exhibition Wild and Majestic: Romantic Visions of Scotland at the National Museum of Scotland until 10 November 2019. Find out more at www.nms.ac.uk/wildandmajestic