In our homes we continually redesign interiors, changing colour schemes and furnishings to suit our tastes. Hamilton Palace was no different and since the 1680s, each successive Duke of Hamilton would instigate re-modelling and renovation of the palace.

Our own oak-panelled drawing room underwent several changes. For instance, the overmantel carved by William Morgan in the 1680s was augmented by an impressive roundel bearing the Duke of Hamilton’s coat of arms at the centre. This addition was made in the 1830s by the 10th Duke when he was made a Knight of the Garter. This means we cannot be completely sure how much of the room we have now dates back to its original construction.

Dr Godfrey Evans, Principal Curator of European Decorative Arts, has spent considerable time researching and collecting archival evidence including bills of work, receipts and drawings which build up a picture of how Hamilton Palace developed over the centuries. Sales catalogues for the drawing room have also helped to establish how it was treated after its removal from the palace in the 1920s.

As part of the conservation process, we undertook specialist analytical techniques of the physical material in an attempt to corroborate the documentary evidence that Dr Evans had obtained. The work was carried out by team of different specialists and student interns. We were all very keen to find out how much of the room could be dated back to the original 1685 construction, taking into account all the renovations and refurbishment it had experienced during three centuries.

Hamilton Palace is located very close to Cadzow Forest, oak woodlands that formed part of the Dukes’ hunting estate. Dr Evans was keen to know whether oaks from the forest had been used in the construction. In the late 17th century, the majority of oak used to build in Britain was imported from mainland Europe or the Baltic – it would be extremely rare and unusual to find native Scottish oak being utilised in buildings at this time.

We brought in the expertise of Dr Coralie Mills, a dendrochronologist, to date the timbers. The oaks at Cadzow still survive and are protected today; their age has been studied so it was possible to make some useful comparisons between them and the oak in the drawing room. Dr Mills studied the two pilaster capitals and concluded that some of the sections of wood were felled in the 1680s, making the capitals original material. Not only that, but at least one section was definitively comparable to Cadzow oaks.

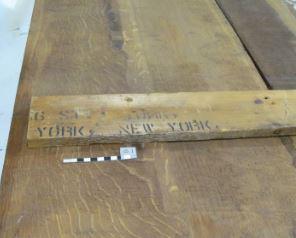

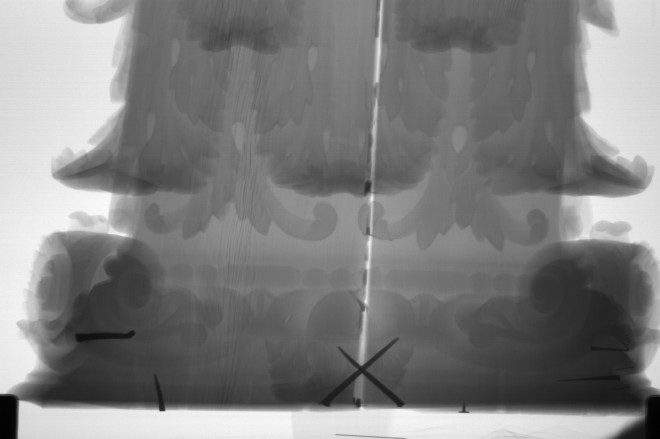

Dr Evans was curious about receipts alluding to restoration work on the overmantel undertaken by the auction company French and Co when the room was shipped to New York in the 1920s. He had found a bill of $1,884 by French and Co for restoration work, the equivalent of $25,000 today. On the surface any evidence of major restoration was not apparent, or least not anything that would credit such a large amount of money being paid. To investigate further, we decided to x-ray the room to see if there were indications of 20th-century restorations from the internal construction.

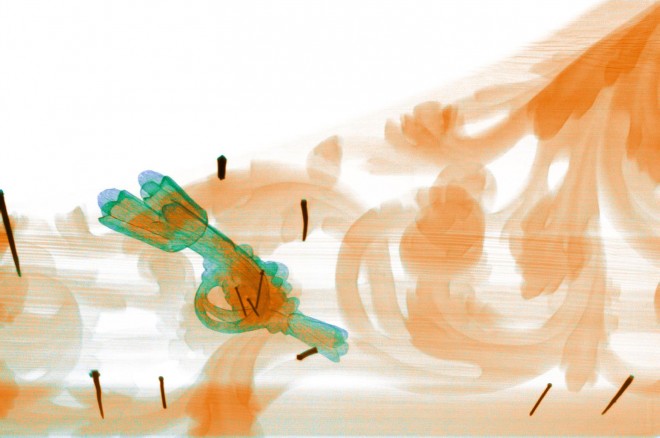

How do you go about x-raying a room? We approached 3DX-Ray, a company that supply and operate portable x-ray systems. Rather than film, their system uses a digital screen which transmits the images directly to a laptop via Bluetooth. We then examined our scans with the help of Kenny Watson, 3DX-Ray’s research engineer. The capitals and the overmantel were x-rayed in their entirety, but nothing in the images suggested that the pieces were anything other than original material.

Another feature of the portable x-ray was its ability to highlight the different materials that make up an object with false colour rendering. In applying this to the overmantel, a restoration of ornate carving was uncovered. The restoration from the rendering appears to be roughly carved from wood but over-modelled with a very dense (possibly lead) filler and painting.

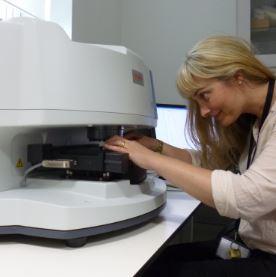

Julia Robinson, our conservation intern, further investigated the surface finishes with Dr Lore Troalen. They analysed if similar varnishes and waxes had been applied to all the oaks. Julia took samples of the varnishes from different areas of the oak panelling and analysed them using a technique called Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR). This technique generates a unique spectra of organic compounds which can be compared with a spectra of known samples. By using this technique, it was found that the oaks had been treated uniformly with shellac-based coating and that some wax had been applied to the capitals.

Invariably the room is still holding on to some of its secrets and we still have many questions that need answering. However, we have been pleased to discover that the room is largely original and that the pieces we have can be dated back to original construction with minimal restoration having taken place.