Peering at reptile fossils in a large shed on the outskirts of Beijing was a very different experience from my fossil hunting excursion the previous month. Here, the air was hot and humid with thunderstorms threatening, but in August we had experienced very different conditions on Skye’s coastline as we prospected for descendants of these same Chinese fossils.

My research interests lie in the Triassic world, 250-200 million years ago when the first dinosaurs roamed the earth, but perhaps surprisingly also the time when many of today’s major groups of animals first appeared; for instance mammals, crocodiles, flies, and turtles. Triassic geography was very different from today, with all the continents joined together as one super continent, Pangaea, which almost completely surrounded a massive sea called Tethys. In this world animals could potentially move relatively easily from one area of the world to another. Consequently trying to better understand this pivotal period in the history of life on earth is necessarily a world-wide pursuit.

Image courtesy of Doug Henderson from N.C. Fraser and D. Henderson. 2006. Dawn of the Dinosaurs: Life in the Triassic. Indiana University Press.

I have been visiting China for well over a decade, first drawn to the potential for Triassic insects in Liaoning Province. However, it was not long before palaeontologist Li Chun, from the Institute of Vertebrate Palaeontology and Palaeoanthropology (IVPP), enticed me into the remarkable world of Chinese Triassic marine reptiles: exquisitely beautiful fossils of monsters with necks longer than their bodies and tails combined. These reptiles inhabited the Tethys Sea alongside a plethora of other strange forms including nothosauroids (mini-Loch Ness monsters) and ichthyosaurs (fish reptiles), as well as the world’s earliest turtles.

Scottish Triassic reptiles are also famous in the form of the so-called “Elgin reptiles”. However these reptiles all lived some distance from Tethys and included pig-sized herbivores called rhynchosaurs and aetosaurs, together with the meat-eating bipedal predator Ornithosuchus. Certainly they were nothing like the monsters I have been studying from Guizhou province in southern China. On the other hand, Scottish ichthyosaurs and plesiosaurs (cousins of the nothosauroids) are known from the younger Jurassic sediments that form parts of the Skye coastline.

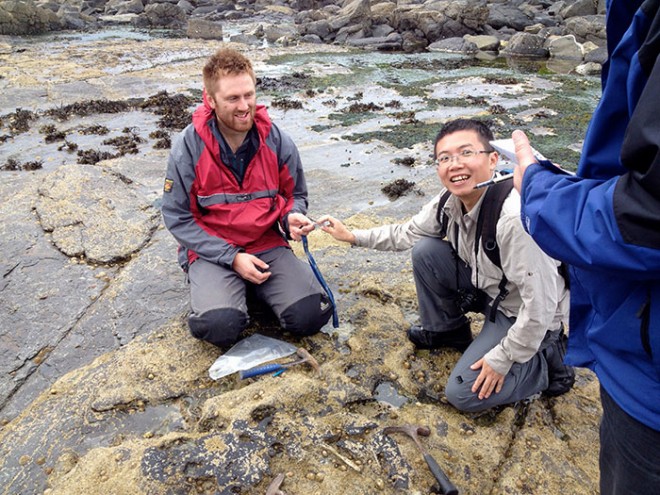

So it was towards the end of August, Li Chun and his colleague Xu Xing visited National Museums Scotland to discuss several possible collaborative projects. High on the agenda was a trip to Skye to hunt for Middle Jurassic dinosaurs and marine reptiles. Middle Jurassic dinosaurs are rare around the world and Skye is one of the few places apart from China where there is the potential for significant remains. Xu is one of the world’s leading authorities on feathered dinosaurs and he has been instrumental in bringing China’s rich Middle Jurassic dinosaur fauna to light. He was therefore keenly anticipating seeing the Jurassic exposures on Skye, not to mention the distilleries on route!

This was the last of the short-sleeved shirts for a few days!

Tom Challands from the University of Edinburgh joined us on the trip. We set off on a remarkably sunny day and were able to enjoy the West Scotland scenery and Tomintoul distillery to the full. Once on Skye we met up with our friends and colleagues Neil Clark from the Hunterian Museum and Dugie Ross from Staffin Museum, but unfortunately the weather turned rather more inclement.

Although the cold wind and occasional squalls of rain were little more than an inconvenience, the rising tide was a more daunting prospect and something that neither Xu nor Li Chun had previously had to deal with in their fossil collecting jaunts back home. Nevertheless Tom’s discovery of a small meat-eating dinosaur tooth in a rock that was rapidly being enveloped by the incoming sea very much attracted Xu’s interest. Tantalizing pieces of large reptile bone plus some dinosaur tracks made the trip a success and hopefully this was the beginning of a long and fruitful relationship between National Museums Scotland, IVPP, and the Universities of Edinburgh and Glasgow.