If there’s one thing I’ve learnt while working on digital content for Photography: A Victorian Sensation at the National Museum of Scotland, it’s that the more things change, the more they stay the same, and when the Victorians got in front of a camera, they were just like us.

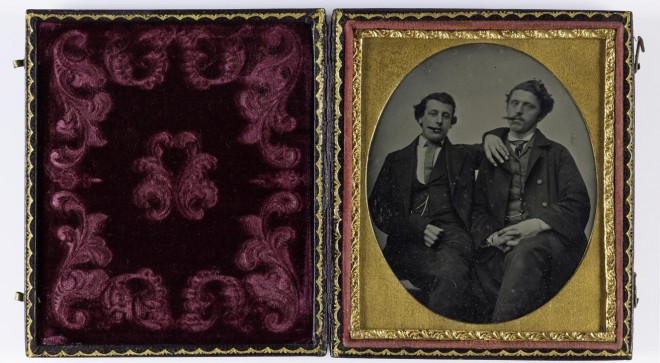

Check out these preening dandies for starters: you can see it in their eyes, they’re gutted to be two centuries too early for Instagram.

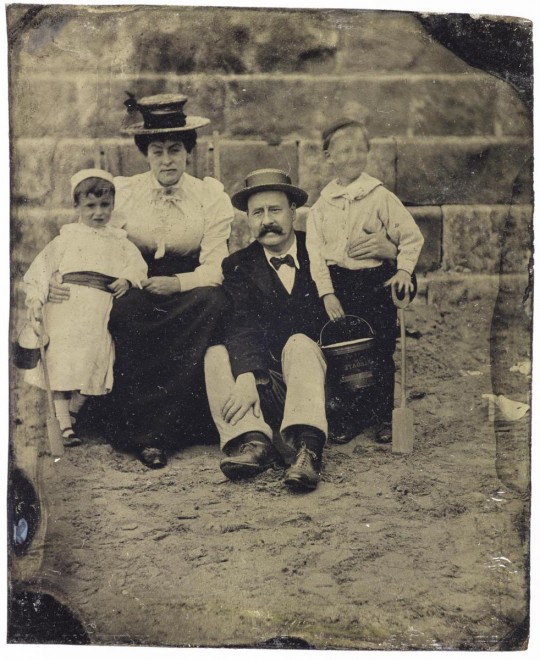

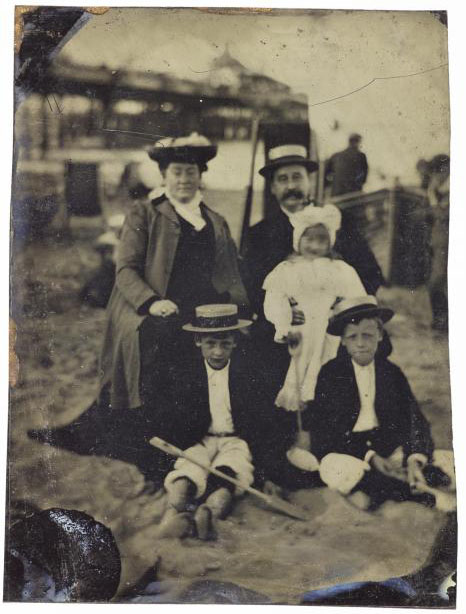

And just as we love to fill Facebook with images of sun-drenched beaches, rum-soaked cocktails, hotdog legs and barbeques, so the Victorians loved to capture their trips to the seaside. This lovely lot returned to Margate every year and each time paid for a photograph to chart their growing family:

However, it wasn’t just people who got in front of the camera. Like us, the Victorians loved their pets. Two hundred years before LOLcats, grumpy cats, piano playing cats and many, many other cats became the runaway stars of YouTube, the Victorians were immortalising their four-legged friends in photographic form. Considering that getting a photo taken in the early 1850s cost around £200 in today’s money, that’s a lot of love. Oddly, cats do not feature much: a little too elusive for early photography perhaps, unless of course they’re stuffed.

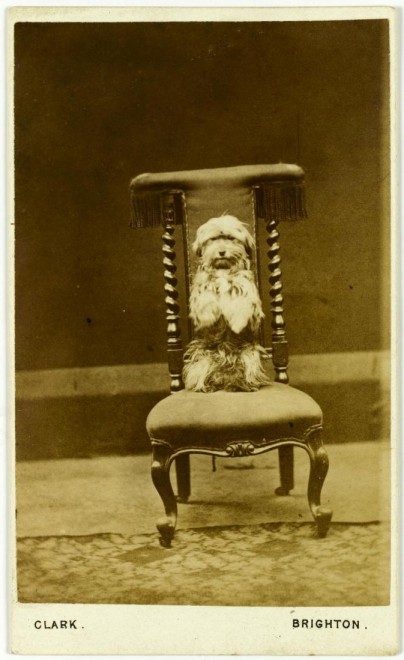

But while cats didn’t fare too well in Victorian photography, dogs were far more popular, alongside horses, donkeys, and even a goat.

This wee cutie looks as if he’s auditioning for Britain’s Got Talent:

Whilst this little spaniel’s daguerreotype portrait is lovingly preserved in a velvet-lined case:

Ever the early adopter, Queen Victoria got in the act, and was often pictured with favourite pets. The savvy Queen, along with Prince Albert, had been quick to see the benefits of photography as a means of reaching the masses and boosting her public profile. If Twitter had been around in the 19th century, she’d have been all over it. #notamused.

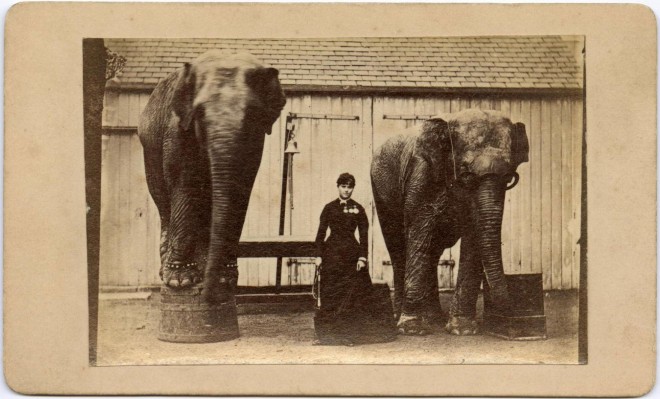

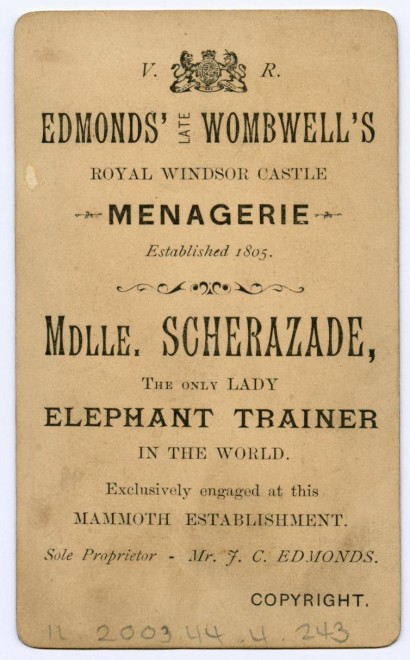

Like Her Majesty, Mademoiselle Scherazade, ‘The Only Female Elephant Trainer in the World’, understood the value of publicity. Here she is pictured with her outsized pets, who, a little internet digging has unearthed, were called Jemona and Abdella.

Mlle Scherazade later went on to marry a lion tamer. I so hope the elephants were bridesmaids. They’d have looked great in the photos.

Speaking of which…

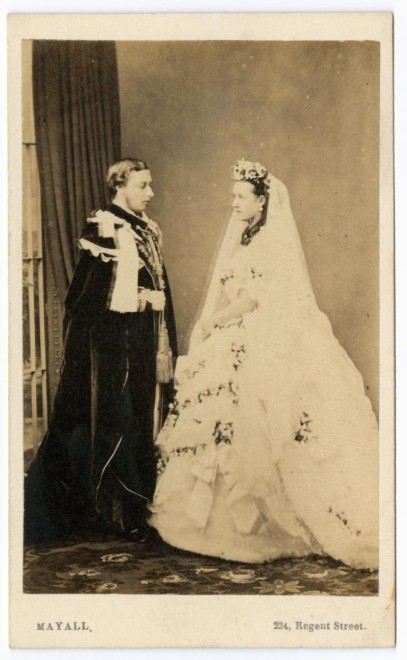

Yes, just like us, the Victorians loved a royal wedding.

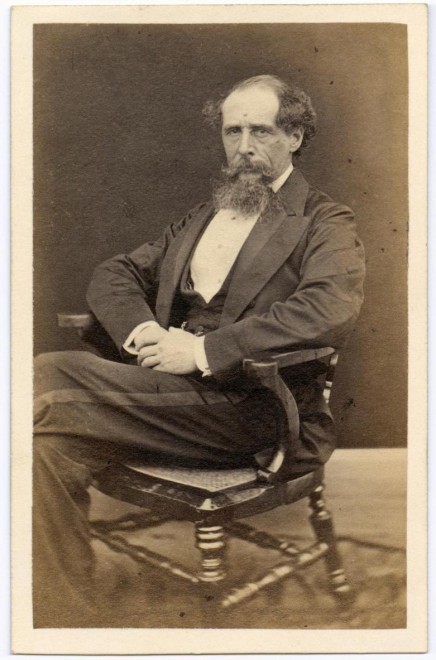

In fact, the craze for collecting cartes-de-visites featuring famous faces was as fierce as the craze for following celebrities on Twitter and Instagram now. I doubt that Charles Dickens could easily have confined himself to 140 characters, but as an inveterate diarist, he’d have made a fantastic blogger.

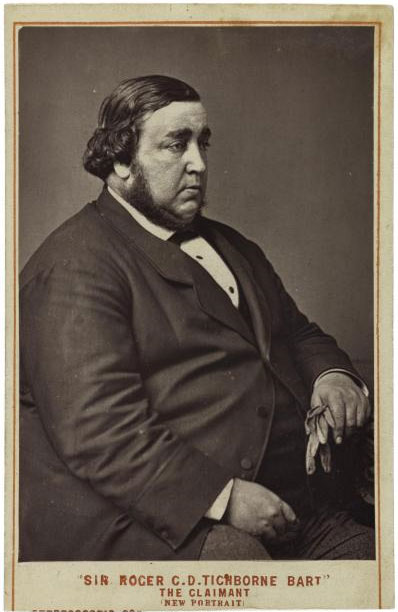

And, just like us, the Victorians liked nothing better than a good scandal. This portly gentleman caused a stir when he claimed to be Roger Tichborne, the missing heir to a baronetcy, thought to have perished in a shipwreck almost twenty years before. He probably wasn’t Tichborne, but nice try all the same.

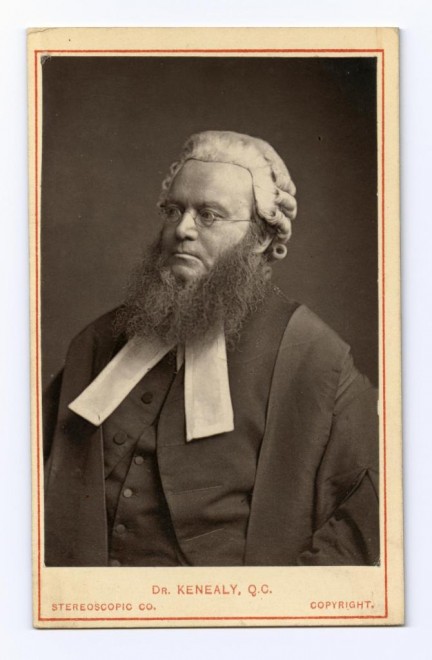

The court case (which the Claimant lost) became a cause célèbre, but pretty much ruined the career of the defending barrister, Edward Kenealy, whose carte-de-visite was also available to collect. Good beard, by the way.

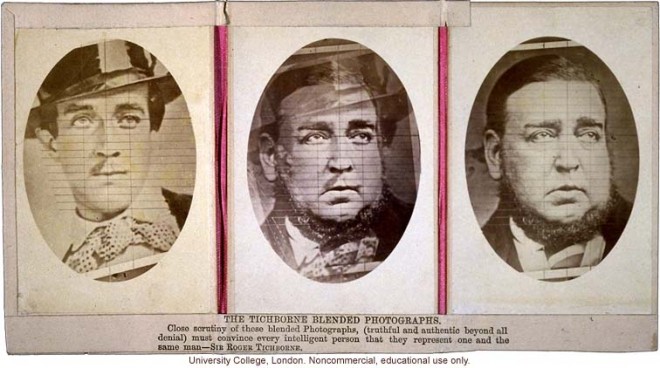

Interestingly, photography wasn’t allowed to be used as evidence in the case, because it was believed to be too easy to fake: this composite photo showing the likeness between the Claimant and the heir was created afterwards – Photoshopping before Photoshop, perhaps?

More notorious still was one Edward William Pritchard, a nefarious doctor who hit the headlines when he was convicted of poisoning his wife and mother-in-law. Here they are pictured together in happier times.

Pritchard was hanged for his crime on Glasgow Green, the last person to be publically executed there.

So, stern, unsmiling and sepia-tinged as the Victorians may seem, at heart they were just as sentimental, self-promoting and vicariously thrilled by scandal as any of us today. Want to meet them? They’re waiting at the museum!

Photography: A Victorian Sensation runs at the National Museum of Scotland until 22 November 2015. www.nms.ac.uk/photography