Conservators are frequently asked to name the most unusual object they have treated. A wasp nest forming the eyes of a plastic doll’s head within a contemporary art sculpture is definitely now top of my list!

Our work in the Conservation Department is very varied and one never knows what one might have to conserve next: that is one of the reasons why it is such a rewarding job. It can also be quite a challenge.

Gérard Quenum’s contemporary sculpture entitled ‘L’Ange’ is a very striking addition to the Museum’s World Cultures collection. It is made of a reclaimed drum, upended, with a plastic doll’s head tinted with brown earth and scorched. Even within the scope of his very individual art, this piece is particularly unique: the eyes of the doll were fabricated by chance in Gerard’s studio by a wasp. He had left it in the corner of his workshop only to find one day that the eye sockets which he had left empty were now filled.

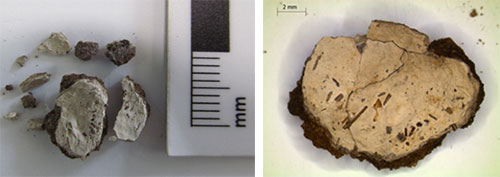

In the autumn of last year I was asked to advise on the conservation of those eyes; they had been damaged while on display and the whole effect of the piece had been greatly diminished. So the following week, one early morning before Museum opening, armed with my stepladder, magnifying visor, head torch and tweezers, I gingerly fished out tiny fragments of wasp nest from the eye cavities, where they had seemingly been pushed by an unknown hand.

The artist had already been contacted by our Curator of African Collections, Sarah Worden, and had planned a visit. He had suggested that he would re-make the eyes himself. However, we all agreed that were it possible to reconstruct the work of the wasp then this would be preferable. We couldn’t very well coax another wasp in to copy the work of her predecessor and so without reconstruction, this fascinating aspect to the sculpture’s creation would be lost.

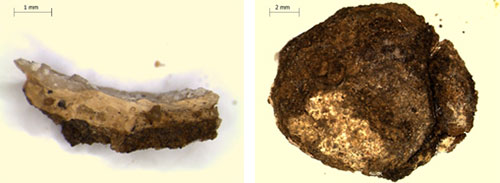

Back in the lab I studied the fragments under a microscope to see how and if the brittle material fitted back together – a jigsaw puzzle more fitting for a Borrower than for my hands! Fortunately I found that although there were a few missing areas I had two almost complete eyes.

The benefit of working at National Museums Scotland is that there is always an expert on hand in all manner of subjects. I enlisted the help of Richard Lyszkowski from our Entomology section to look at the pieces and tell me a bit more about how the nest (or in fact nests – as there was one in each eye) were constructed.

He was very surprised by the wasp’s work. He identified what he considered typical wasp nest materials: a brown organic mass of fibres. But on top of this was the striking white layer which Quenum had admired. This, the artist had conjectured, was probably taken from the white muddy shores of a lake outside. A quick trip to see Lore Troalen in our Analytical Science section confirmed this was calcium based and therefore could be a chalky material. Richard thought this was unusual wasp behaviour, as usually the insects would take steps to make their nests as unobtrusive as possible rather than daubing them in white. This aspect remains a bit of a mystery and any feedback from you, the public, would be greatly appreciated.

When we told Gérard of our assessment he was much amused by this analytical assessment of part of his sculpture.

We also discovered that there was another applied layer over the top of this white, which Gérard had applied to preserve the wasp eyes. Though this did preserve the eyes as they were, it also had the unfortunate effect of entombing the wasp larvae. I found fragments of insects within the eye sockets and it is probable that the pupated wasps could not escape their nests. At any rate the eyes would have been destroyed if they had.

Meanwhile my reconstruction was not complete. Though I had reassembled the fragments and stuck them together, I still had to attach them into the eye sockets, fill the missing areas, and in the case of the right eye, find a way of replicating the surface finish which sadly had been lost in this case.

Following many trials, I finally concocted a combination of cellulose powder and an acrylic adhesive, which I toned slightly to match the original. This also replicated the slightly lumpy surface texture of the original eyes. Back in the gallery, I carefully attached the wasp nest fragments back in place using a conservation grade adhesive and then filled the gaps with my pre-tested mix to match the picture I had of the eyes before the damage.

Gerard Quenum was due the following week to survey the results. Fortunately he was satisfied with the outcome. It was fascinating to hear him describe his sculpture, what it meant to him and the techniques he used after my own at times agonising but ultimately very satisfying experience of working on ‘l’Ange’. You can see Gerard talking about the sculpture in the video below.

[vimeo 60243013 w=500&h=280]

You can see the newly restored sculpture in the Artistic Legacies gallery, on Level 5 of National Museum of Scotland. We’ve now decided to keep the sculpture in a case, to protect it. You can find out more about ‘L’Ange’ here.