Explore more: uncover the full story of Kilmartin Glen in our Hub.

Every part of Scotland is historic, with stories for the telling. Whether rural or urban, landscapes and communities are the ultimate source of the objects we collect and display. Yet, it is easy to be so preoccupied with the objects themselves that we lose sight of where those objects were made, used, found, and given meaning. In this, the first of a six-part blog series by historian and writer David C. Weinczok, we zoom out to reflect on the places beyond the glass cases.

In the dappled morning light, Kilmartin Glen awakens. The sun’s first tendrils embrace the Moine Mhòr – the ‘Great Moss’ – from the Crinan Canal to the great glacial terrace down which prehistoric waters surged. Shadows extend like fingers growing from the base of the standing stones of Nether Largie and Ballymeanoch. The grooves of 5,000 year-old carvings hewn into rocky canvases are thrown into sudden, stark relief. The snaking River Add is warmed on its journey past an ancient hilltop capital into the turbulent Sound of Jura. A rooster calls out from the farm to the north, echoing over the parapets of Carnasserie Castle. In the heart of the village the church door creaks open, the graves of warriors 500 years gone waiting for the day’s first footsteps to fall on them.

Kilmartin Glen in Mid-Argyll is one of the most archaeologically prolific places in northwest Europe. In a low-lying area some five miles long and wide and surrounded by modest hills like a great dish, there are over 800 historic sites. On the maps of the Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland (RCAHMS), no other area of Argyll is lit up by so many remnants of the past. Yet, unlike the Heart of Neolithic Orkney centred on the Ness of Brodgar and Maeshowe, mainstream fame largely eludes it.

The Great Moss

Within the narrative of Kilmartin Glen, the raised bog of the Moine Mhòr (pronounced ‘Moyn ya-vore’) is both hero and antagonist. Between 4,000 and 2,500 years ago Scotland’s climate markedly deteriorated. Increased rainfall and dropping temperatures led to degraded soil quality and a reduction in vegetation, in turn reducing herbivore populations such as deer. Deep peat formed in previously arable lands, and upland settlements across Scotland were abandoned for milder, more easily supplied locations.

The Moine Mhòr devoured ten-foot-tall standing stones, leaving only their peaks visible to their builders’ descendants, like skerries in a sea of salt and peat. They would not be fully revealed again until the nineteenth century, when Improvement schemes implemented by the Malcolms of Poltalloch – funded largely by profits from Jamaican sugar and tobacco plantations worked by enslaved people – reclaimed land for agriculture.

Yet while the Great Moss long marked the boundaries of human habitation, it is also a champion for wildlife and the natural environment. Like Sutherland’s Flow Country in miniature, it captures vast amounts of carbon dioxide and hosts a flourishing wetland ecosystem that today delights residents and visitors alike. It is one of Europe’s most delicate and threatened habitats, its future now hopefully secured by its status as a National Nature Reserve.

Dunadd, heart of the Scots

Dunadd is a place whose subtlety in the landscape belies its importance. At just 54 metres high, it is far from the tallest hill around. Viewed across the flatness of the Moine Mhòr, Dunadd is almost camouflaged by the much higher ridge immediately to the east. Yet this modest stone outcrop was one of the most important sites in the crucible of nations from which the early Kingdom of the Scots emerged.

Dunadd was a major power centre of Dál Riata, the Gaelic-speaking kingdom established on the west coast of Scotland during the 6th century AD. However, occupation and fortification of the hill goes as far back as 200 BC. Near Dunadd’s summit, with sweeping panoramic views, is a footprint in stone, used during king-making ceremonies throughout the Gaelic-speaking world. Similar footprints can be found at Finlaggan in Islay, Camusvrachan in Glen Lyon, Southend in the Mull of Kintyre, among others.

In all my visits to Dunadd, I have never seen anyone able to resist the urge to pull off their shoes and socks and see if their foot fits, myself included. The print is in fact a cast meant to protect the original, but such are the compromises we make between authenticity and preservation.

Through the coastal waterways leading to the River Add, which weaves through the Moine Mhòr, the world came to Kilmartin Glen. Adomnan’s seventh-century chronicle Life of Columba tells of French ‘wine-ships’ docking near Argyll’s caput regionis, ‘the head of the region’, interpreted by pioneering Argyll archaeologist Marion Campbell as referring to Dunadd. The hillfort was once accessible by water, with small boats once able to sail up the River Add nearly to its base.

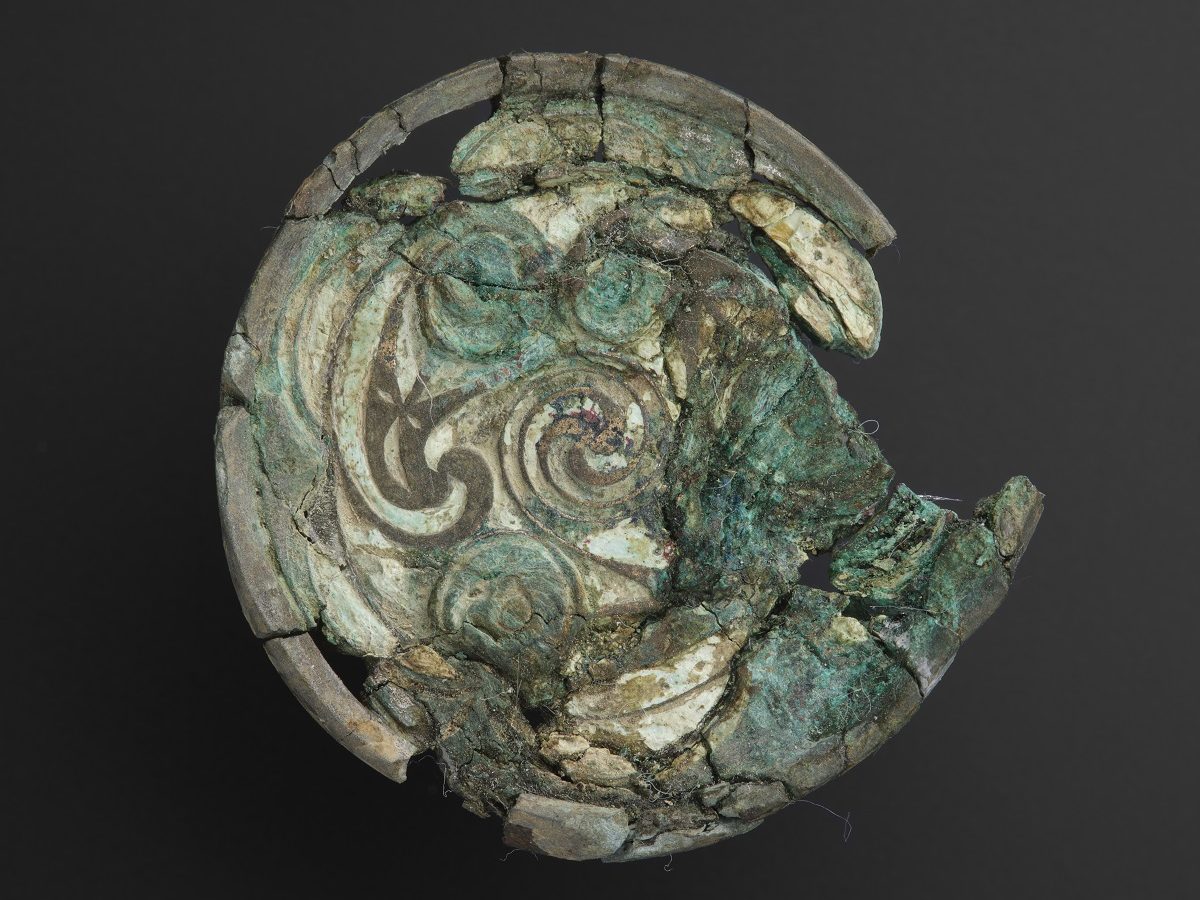

During early 20th century excavations funded by the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, an enamelled interlace disc from c.575-850 of possible Frankish origin was found here. There was also orpiment, a sulphide of arsenic used as a yellow pigment in the illumination of early Insular Christian manuscripts. Resources for the illumination of manuscripts were likely imported to Dunadd and then sent on to Iona, connecting Kilmartin to the wider North Atlantic monastic world. Our collections contain a tessera from a Byzantine glass mosaic with gold leaf, demonstrating that connections extended to the heart of the Mediterranean and beyond.

Control over the production and distribution of bronze objects was, as the name implies, one of the hallmarks of power in the Bronze Age. Kilmartin Glen was influential in this revolution, and continued to be a centre of bronze working until well into the Early Medieval period. Finds now in our collections include a gold and garnet stud and sheet bronze fragment imported from Northumbria c.600-700 AD, an enamelled copper alloy disc from a hanging bowl c.575-850 CE, a loop-headed pin imported from Ireland, and two moulds for creating penannular brooches. Precious metal dress-fasteners like these, for example the Hunterston Brooch, exchanged hands throughout the Insular world during the Early Medieval and Viking ages.

The Linear Cemetery

Strung out like the dots of a map’s trail through the centre of Kilmartin Glen are a line of cairns, collectively called the ‘Linear Cemetery’. Five of an original seven cairns survive to varying degrees today. Some can be entered, though that was never the intention, while others are reduced to rubble. The hills that narrow the glen’s northern boundaries urge the eyes and momentum of travelling feet towards the focal point of the cairns. Individual sites within the historic landscape of Kilmartin Glen are intimately interconnected, even though some monuments predate others by thousands of years.

Bronze Age round cairns represent an important shift in ancient funerary practices. Whereas earlier cairns were raised for groups of people, those in the Linear Cemetery were for individuals. They are also the earliest funerary monuments that regularly contain grave goods for modern archaeologists to discover. This shift coincided with an end to the creation of new rock art sites, attributable in part to a time of climactic degradation.

Within Glebe Cairn, adjacent to Kilmartin Museum, a jet necklace of tremendous value and intricacy was found with a woman’s skeleton. Her luxurious grave goods also included a beautifully decorated food vessel, one of the finest in Scotland that drew inspiration from connections with Ireland. The necklace was later lost in a fire which consumed nearby Poltalloch House, home of the Malcolms of Poltalloch. Our collections contain a similar jet necklace and bracelet found in another Bronze Age burial in the glen.

Kilmartin’s Bronze Age cairns have yielded a variety of vessels, including early styles of Beaker vessels, indicating the arrival of new peoples, ideas and styles of material culture. It was in the Bronze Age that Kilmartin Glen truly flourished, with many of its best-known monuments including the Linear Cemetery and Temple Wood taking their current form.

Symbols in stone

Not all archaeological finds can be removed from the ground that holds them. Some are woven into the land itself. Scotland’s Rock Art Project (ScRAP) has recorded 332 rock art panels in and around Kilmartin Glen, accounting for a staggering 10% of all known rock art sites in Scotland. Most were made between 4,000 – 2,500 BC, primarily on gently sloping, south-facing rock outcrops.

Unlike funerary monuments and standing stones, which were usually meant to be noticed from far away, rock art was most often created away from well-worn paths. Perhaps they were meant to retain an intimacy for the visitor, or to be known only to local communities. As with the deliberate destruction and depositing of bronze objects in lochs and bogs, the creation of rock art was likely a communal event intended to endure in collective memory.

The meaning of these motifs is now lost to time. The same cannot be said of their significance, however, as Kilmartin’s modern residents enthusiastically display their own renditions of them in shop windows, roadside graffiti, and locally produced goods. It’s a rare design that can boast popularity after more than 6,000 years.

In Kilmartin Glen, dynamic arrays of rock art motifs such as cup-and-ring marks are found at Achnabreac, Kilmichael Glassary, Cairnbaan, and Ormaig. While none of our rock art examples of this type hail from Kilmartin Glen, we do have another example of a message in stone that we can understand. Ogham was an Early Medieval alphabet used throughout Ireland and the west of Britain. It is written as stroke-marks, as seen in our example from Poltalloch and on another carved slab atop Dunadd where the Ogham is accompanied by a carving of a boar.

Kilmartin past and future

Though our objects put the spotlight on prehistory and the Early Medieval period, the story of Kilmartin Glen of course does not end there. Carnasserie, Kilmartin, and Duntrune castles, as well as the Hebridean-style grave slabs in Kilmartin Churchyard, speak to potent happenings throughout the Middle Ages. The first printed book in Gaelic, a translation by Bishop Carswell of John Knox’s Book of Common Order, was made at Carnasserie. The Highland Clearances dispersed many Kilmartin residents to Glasgow, the Americas, and beyond, while the exploitative windfalls of colonialism drove the building of mansions and an increasingly tangible human dominance over the land in the age of ‘Improvement’.

Kilmartin’s past, as illuminated by our objects, was shaped by drastic environmental change, ebbs and flows in the distribution of power, and the creation of things of staggering beauty in times of both plenty and hardship. Things which once seemed eternal have proved ephemeral, while others created in and for a specific moment have endured long beyond their makers. Let that be wisdom of Kilmartin Glen, and of the objects from it.

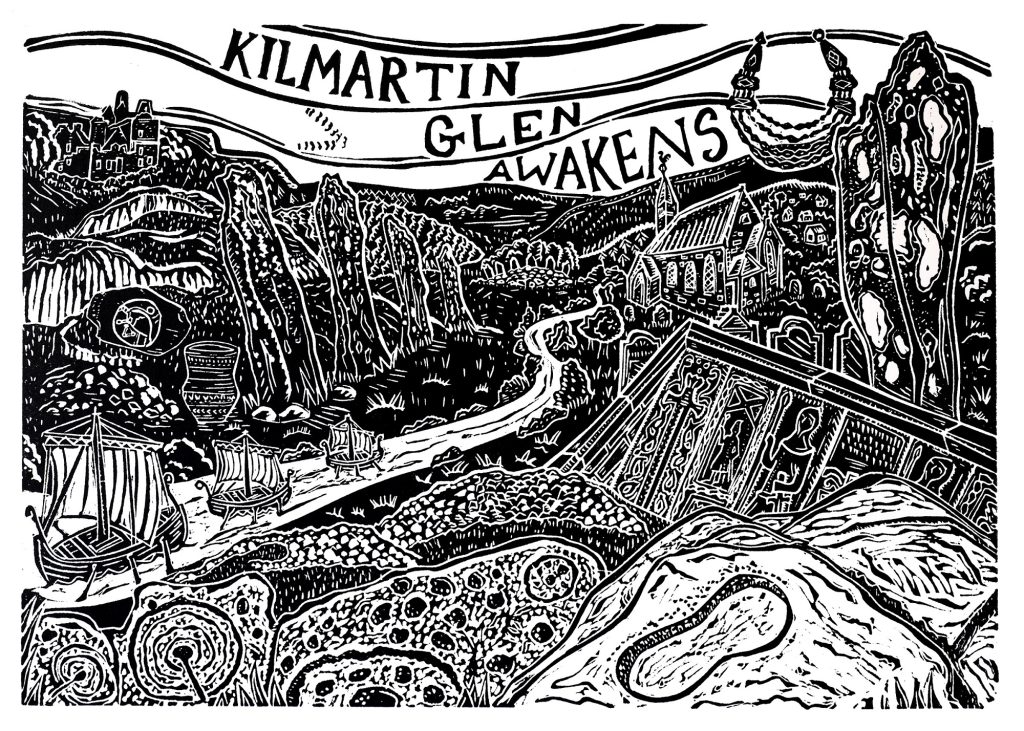

Enjoy a minute-long look at artist Pamela Scott’s rendition of Kilmartin Glen.

Music credit: ‘Long Road Ahead B’ by Kevin MacLeod is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 license: Source

Dundee-based illustrator and printmaker Pamela Scott was commissioned to produce a unique artwork as part of this article.

See the creative process in action in this time-lapse video by Pamela Scott.