Bond. James Bond. These three words are some of the most famous in cinematic history. For almost 60 years and across 25 films, the Bond movies have grown into one of the most recognisable and profitable film franchises of all time. Scotland – its people and its places – has been part of the journey, from Sean Connery to Skyfall Lodge. In this blog, Dr Calum Robertson looks at some of the other cameos Scotland has played in the making of 007.

Before James Bond was a hit on screen, he was a hit in print. Beginning in 1953, Ian Fleming wrote ten James Bond novels before the film release of Dr. No in October 1963. In these early books, Bond is portrayed as a certain type of quintessential English gentleman. A former naval officer with a taste for the finer things in life and an ill-defined sense of duty. It would not be until Sean Connery was cast to play the role of Bond on screen that Ian Fleming began to write a Scottish backstory for his lead character.

Fleming’s own ancestry lay north of the border. The author’s grandfather, Robert Fleming, was a pioneering financier and one of the leading lights in the development of the investment trust movement. Born in humble circumstances in Dundee in 1845, Robert cut his teeth as a clerk in the city’s booming jute mills before establishing the Scottish American Investment Trust in 1873.

The success of the Scottish American Investment Trust was based on shrewd and well-researched investments in the rapidly expanding railroads of the United States. Over the course of his life, Robert Fleming made hundreds of trips across the Atlantic to gather information about investment opportunities, ensuring that his company was one of the best-informed in the business.

Managing other people’s money is, of course, a good way of making money for yourself. In 1880 Robert Fleming was able to purchase a property in the genteel town of Newport-on-Tay on the north coast of Fife. It was there, in the family home ‘Tighnavon’, that Ian Fleming’s father Valentine was born in 1882.

It wasn’t long until the bright lights of London were calling, and Robert and family eventually ended up in Joyce Grove, a vast Jacobean-revival house in Oxfordshire. However, neither father nor son forgot their Scottish roots. Robert Fleming spent almost every summer until his death in 1933 at the Black Mount estate in Argyll, and Valentine had a shooting lodge built at Arnisdale on the shores of Loch Hourn, which was completed in 1916.

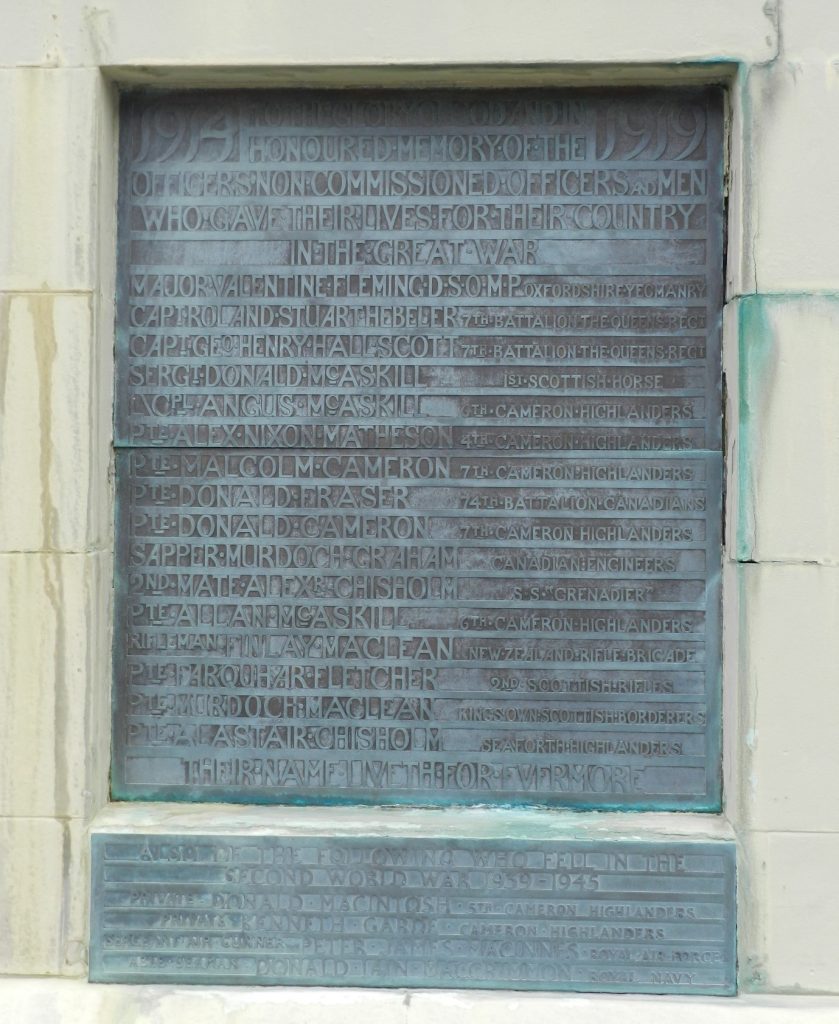

A year later, in 1917, Valentine Fleming was killed in northern France whilst on active service during the First World War. He was 35 years old and Ian, the second of his four sons, was eight days short of his tenth birthday. Valentine Fleming is remembered in Scotland on the Glenelg war memorial, close to his house at Arnisdale. Designed by the noted architect Robert Lorimer and sculpted by Louis Deuchars, Glenelg’s war memorial is one of the most striking and emotive First World War memorials constructed in Scotland.

Ian Fleming’s ancestry was not the only literary development that belatedly bled into his writing. A similar story is reflected in the introduction of what would become one of cinema’s most iconic props: James Bond’s gun.

In the first five James Bond novels, Ian Fleming armed his hero with a .25 calibre Beretta M418. The .25 Beretta is a small, so-called ‘pocket pistol’ of the type the author was familiar with from his days as a naval intelligence officer during the Second World War.

However, in May 1956, Fleming received a letter from a G. Boothroyd of 17 Regent Park Square, Glasgow which would make him reconsider this choice of firearm. By day, Geoffrey Boothroyd worked as a technical representative in the Glasgow offices of Imperial Chemical Industries, but in his spare time he was a leading gun expert and collector.

In his letter to Fleming (which is both long and detailed) Boothroyd wrote:

“I have by now got rather fond of Mr. James Bond. I like most of the things about him, with the exception of his rather deplorable taste in firearms. In particular I dislike a man who comes into contact with all sorts of formidable people using a .25 Beretta. This sort of gun is really a lady’s gun, and not a really nice lady at that.”

Boothroyd’s contention with this original choice of weapon was its stopping power. A semi-automatic pocket pistol like the Beretta M418 (or the FN Baby Browning which Fleming himself carried during his wartime service) could be easily concealed, but was not much use in decisively stopping the tenacious SMERSH agents the literary James Bond frequently encountered.

Over the course of their correspondences, Boothroyd and Fleming settled on the perfect firearm for Bond: the Walther PPK. This stylish double-action pistol was still capable of being concealed, but was considerably more powerful than a pocket pistol. Best of all, unlike a revolver, the Walther PPK had few protrusions that would catch on a dinner jacket in the event of a quick draw. Grateful for the detailed advice Boothroyd provided, Fleming immortalised him as ‘Major Boothroyd’ – MI6’s armourer – in his 1958 novel Dr. No.

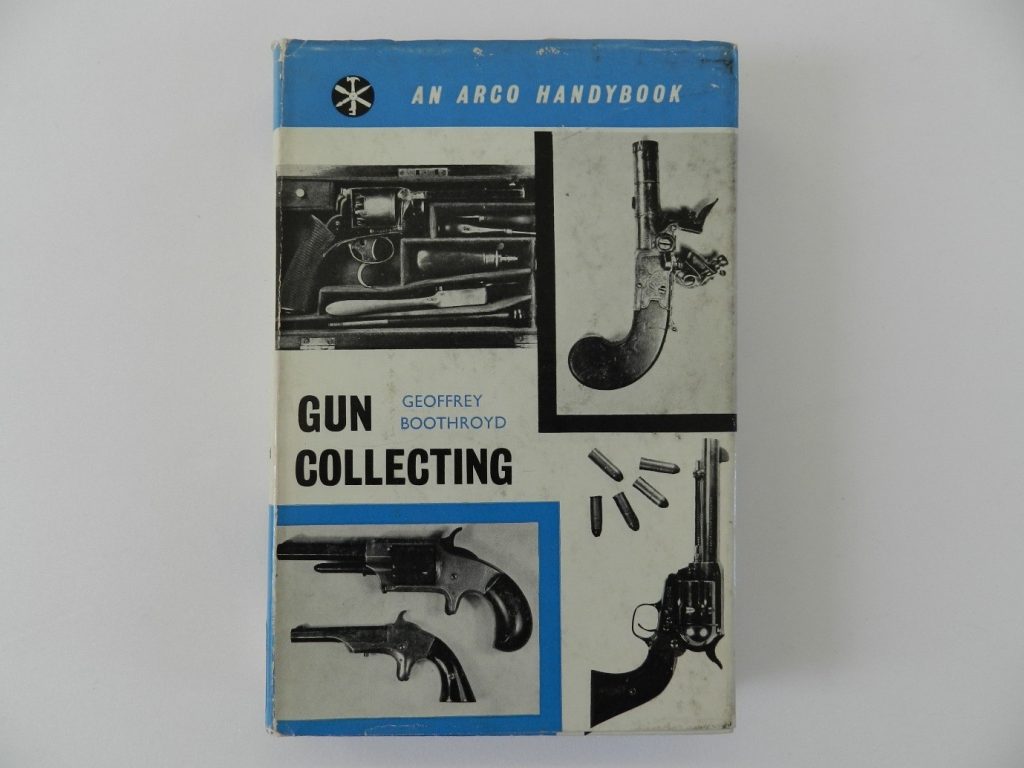

Geoffrey Boothroyd’s own writing career began in 1961 with the publication of Gun Collecting. By this time Boothroyd had amassed a personal collection of around 45 firearms, however it was to the extensive arms collections of Glasgow Museums that he turned for the many examples of historical firearms that are illustrated in his book. Boothroyd would go onto write a number of books about guns, many of which remain required reading to this day.

This look at some of the lesser known relationships between James Bond and Scotland has shown that aspects of Bond’s characterisation and visual identity are not necessarily fixed. With more Bond novels and films in the pipeline, perhaps there are further chapters to be written and scenes to be filmed involving Scotland’s people, places and past.

Further reading

Fleming, Fergus, ed. The Man with the Golden Typewriter: Ian Fleming’s James Bond Letters. London: Bloomsbury, 2014.

Fleming, Ian 1958. Dr. No. London: Jonathan Cape, 1958.

Lycett, Ian. Ian Fleming. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1996.