A dazzling Renaissance silk doublet is now on display in the Fashion and Style gallery at National Museums Scotland. In this blog Helen Wyld, Senior Curator of Historic Textiles, and Calum Robertson, Curator of Modern and Military History, take a deep dive into the history of the doublet, and its relationship to both fashion and war.

At over 450 years old, the doublet is an extremely rare survival. Due to its fragility it will only be displayed for a limited amount of time. But who would have worn this garment, and what would it have said about its wearer?

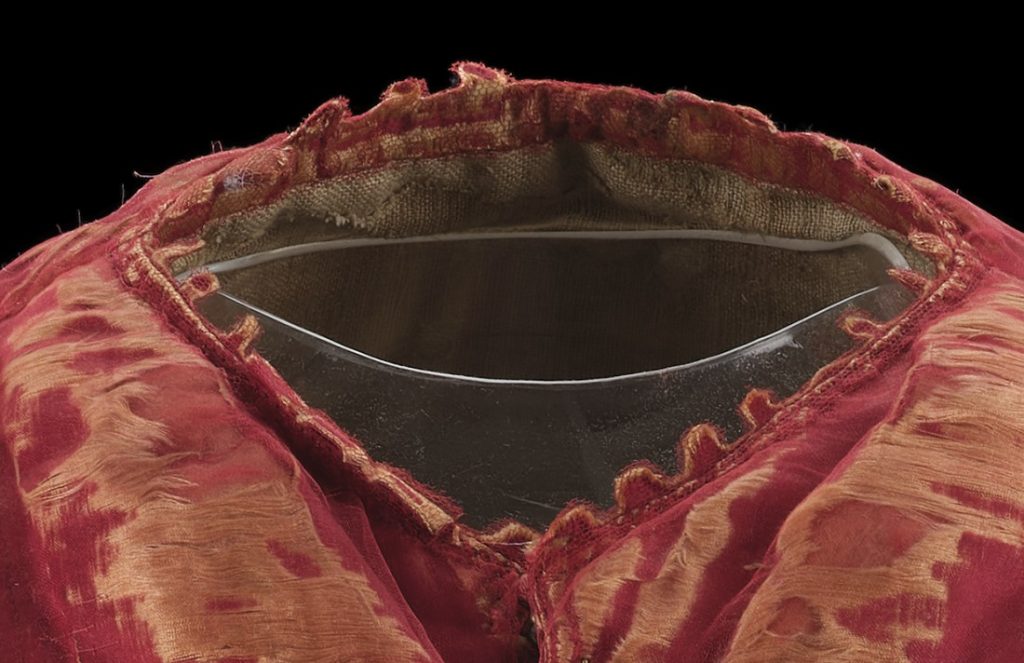

Made from luxurious red silk satin, the doublet immediately strikes us as a high-status garment. With an exaggerated point at the waist, delicate snipped collar and cuffs designed to frame a frilled shirt, and hand-made buttons decorated with silk embroidery, it would have formed part of a fashionable ensemble in the mid sixteenth century. It is probably Italian, and similar garments can be seen in Italian paintings of the period.

However, recent scholars have suggested that this may actually be an ‘arming doublet’, designed to be worn under plate or mail armour. Is this possible? Let’s look at the evidence.

A tale of war and the origin of doublets

When we acquired the doublet in 1983, it was thought to have been worn in battle, specifically at the 1535 Siege of La Goulette (Tunis) by the 2nd Marquis of Modejar, who was Captain General of the Cavalry of the Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V. The siege of La Goulette was part of Charles V’s campaign to seize Tunis, then controlled by the Ottoman Empire. As proof of this story, two cuts – one in the arm, one in the back – were seen as evidence of the Marquis’s wounds. But can this story be true?

The shape of the doublet, with its pointed waist (known in English as a ‘peascod’), suggests a date closer to 1550, making the link to the siege of La Goulette untenable. However, the idea that this garment was worn in battle is not as far-fetched as it may seem. The origin of the doublet – a close-fitting, padded garment worn on the upper body – actually lay in the medieval period, when it was designed specifically to be worn under armour. Our doublet still retains elements of this early function. Most obviously, it is quilted, with a layer of cotton padding sandwiched between the outer layer of silk and the linen lining.

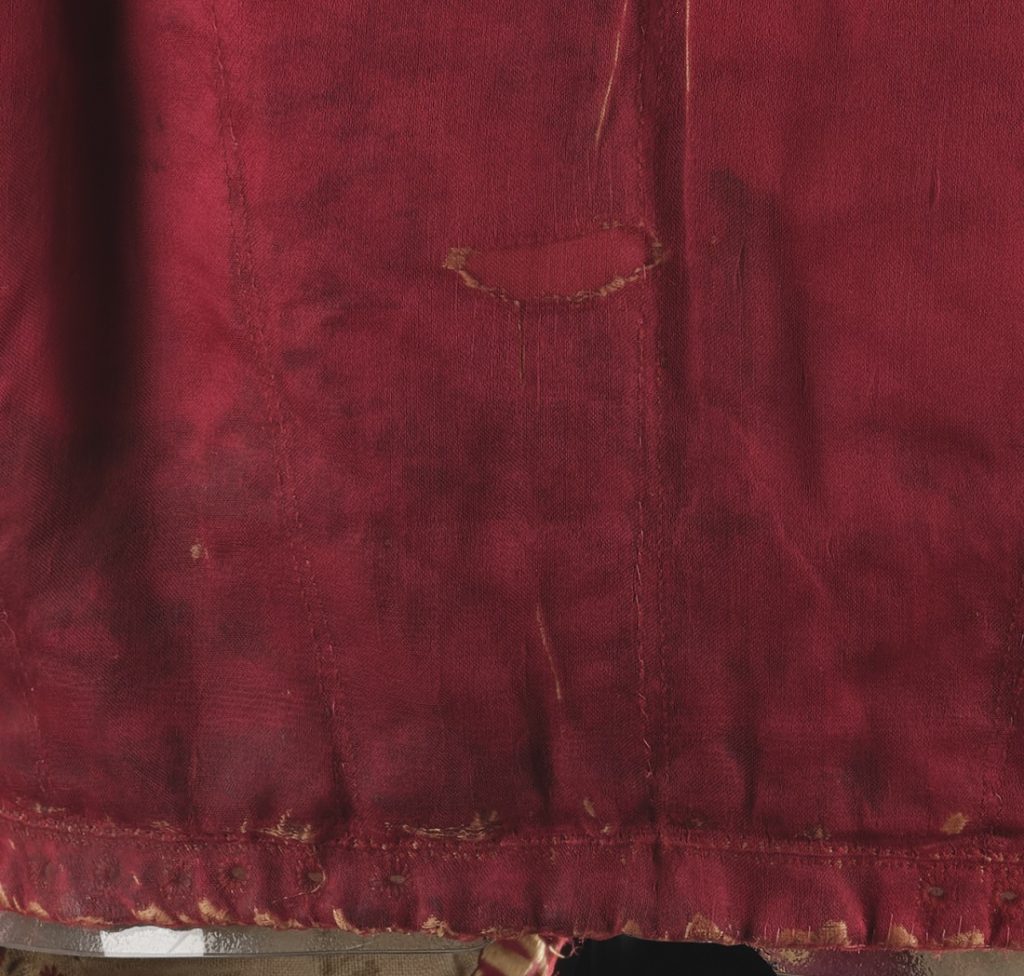

Doublets later evolved as a kind of underwear in non-military contexts too, and were always worn under an outer coat or tunic. To hold the doublet in place, it would be laced to the wearer’s breeches with cords. Our doublet shows signs of this usage. A row of stitched eyelets around the lower edge, which has been reinforced with a band of coarse linen, would have held these cords. But in the later 15th century, men began wearing doublets as outerwear, and they start to be made of richer, more fashionable materials, like our red silk satin example.

Eyelets and aiglets

Despite the clearly fashionable appearance of our doublet, costume historian Janet Arnold still suggested that it might be an arming doublet, capable of being worn under armour. This was largely due to a second set of stitched eyelets, around the top of each sleeve. These too could have held cords or laces, in this case to attach plate armour to the body.

A portrait of the English Lord High Admiral Lord Clinton in 1582 shows the wearer in a silk doublet with decorative cords streaming from shoulder eyelets, and a leather jerkin.

The shoulder cords, and those tying the centre front of Lord Clinton’s jerkin, are tipped with metal tips known as ‘aiglets’ (or aglets) – literally, small needles. Known collectively as ‘points’, these cords, and their decorative aiglets, were frequently used on both civilian and combat clothing.

In Lord Clinton’s portrait, the points are at least partly decorative, but their position on the shoulder suggests the wearing of armour. Some late 16th century portraits show shoulder aiglets that clearly have no function but are exaggerated in size, suggesting a symbolic meaning.

In fifteenth-century Italy, shoulder eyelets in doublets had long been worn on otherwise civilian dress, and they can often be seen in portraits. Curator of arms and armour Tobias Capwell has suggested that these wearers were using the shoulder eyelets, with their martial associations, to suggest a kind of chivalric virtue based in military prowess. Our doublet, though dating to the sixteenth century, seems to be making a similar claim; it may be the only surviving garment to contain these intriguing signs. Interestingly, the eyelets show no signs of having been used.

‘An officer and a gentleman’

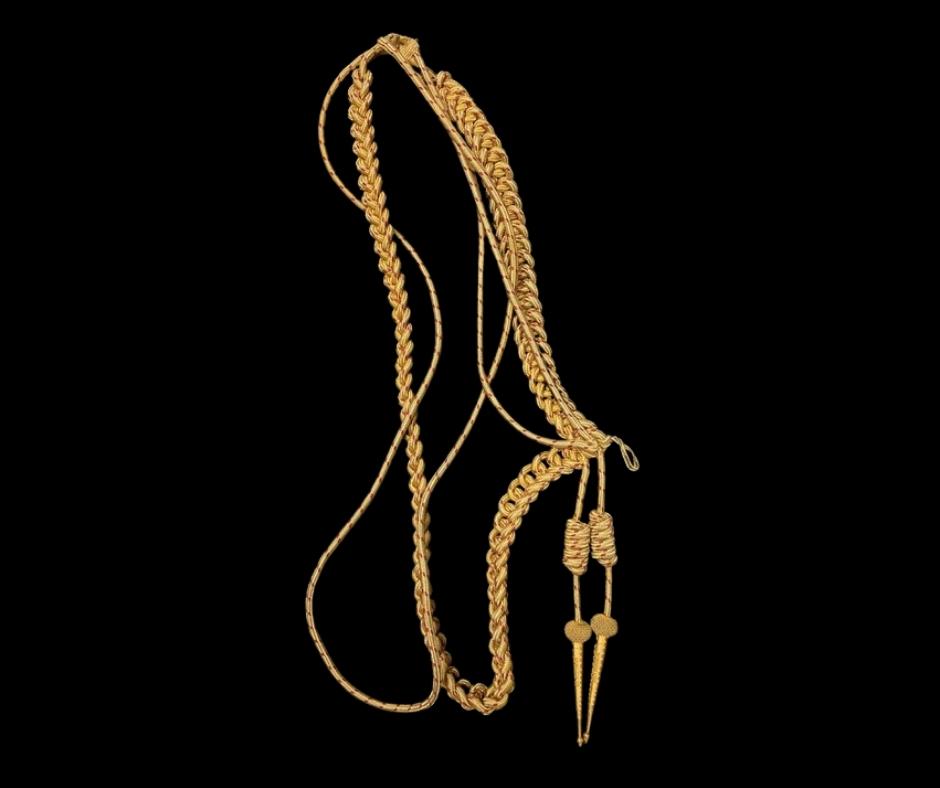

Distant as the arming doublet now seems, something of its martial origin and decorative form remains in the continued wearing of aiguillettes. Aiguillettes are the descendants of both practical arming points and decorative aiglets, and still form an important and highly visible part of the uniforms of many contemporary armies, navies and air forces across the world.

Typically made of gold thread, the wearing of aiguillettes today refers to the 15th and 16th century aiglets illustrated above: suspended from the shoulder, looped under the armpit, and secured by button to the wearer’s front.

The metal points that give aiguillettes their name are now exaggerated in size and typically decorated with symbols associated with wearer’s branch of armed service.

It’s not clear if aiguillettes were worn continuously from the 15th century onwards. However, with the development of professional armies and standardised uniforms from the 17th century onwards, the wearing of aiguillettes slowly spread as a symbol of military authority.

The wearing of aiguillettes has always been reserved for specific groups and individuals. In today’s British armed forces, this includes the highest-ranking officers – admirals, field marshals and marshals of the Royal Air Force – as well as certain staff officers working for a commander or in headquarters.

Aiguillettes continue to be worn as a performative piece of costume that articulates a very visual message of authority and hierarchy. They also reflect a sense of moral hierarchy: the aiguillette is a ‘golden thread’ (or perhaps a golden cord) between today’s military officers and much older ideas of martial leadership and chivalry.

Further reading

Janet Arnold, ‘Two Early Seventeenth Century Fencing Doublets’, Waffen- und Kostümkunde, 1979, pp. 107-120

Tobias E. Capwell, ‘A Depiction of an Italian Arming Doublet, c. 1435-45’, Waffen- und Kostümkunde, 2002, pp. 1-20

John L Nevinson, ‘A Sixteenth Century Doublet’, Documenta Textilia: Festschrift für Sigrid Müller-Christensen, Munich 1981, pp. 371-375