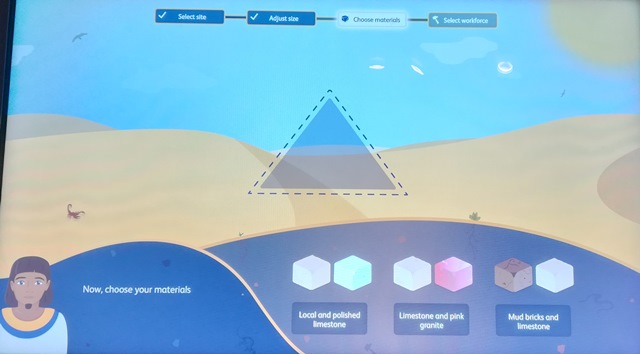

Visitors to the new ancient Egypt gallery at the National Museum of Scotland, Ancient Egypt Rediscovered, can play an interactive game called ‘Build a Pyramid’. The game allows the player to make the decisions faced by an ancient Egyptian king when deciding to build a pyramid, such as scale, location, materials, and size of workforce.

We faced a similar array of choices when commissioning two touchable objects for an interactive in the gallery. Real objects from our collection are too fragile and precious to be touched by thousands of people, as they would very quickly get dirty and damaged. Instead, we often buy or commission ‘touch objects’ made of robust and long-lasting materials to allow people to interact with objects using more than just their eyes. Not only is this good for people with visual impairments, but it allows everyone to feel the differences between different materials and different construction techniques, and to imagine what it might be like to handle actual historic artefacts (although of course as curators we normally wear gloves!).

We decided to focus on contrasting the two stone-carving techniques used in ancient Egypt, one of which was largely specific to ancient Egypt, while the other is still widely used throughout the world. With two examples of carving used for different purposes, it also seemed obvious to demonstrate this with two different types of stone. But which stones to use, and how big, and who to commission to do the project?!

Identifying the two different techniques used on ancient objects in the gallery, and in more recent architecture elsewhere, would allow us to make informed choices for the materials.

Raised relief carving

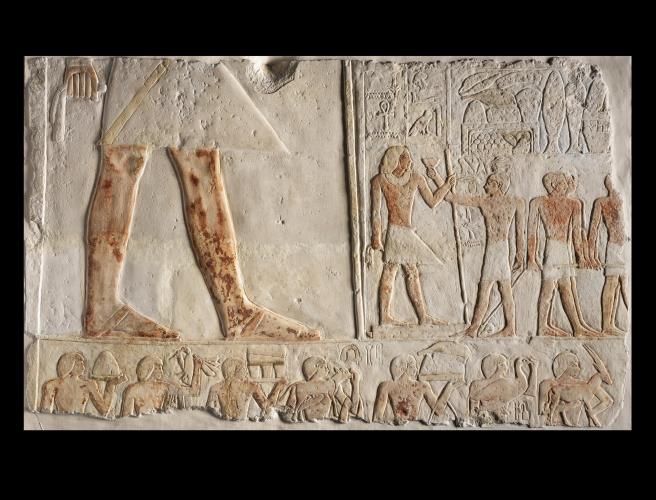

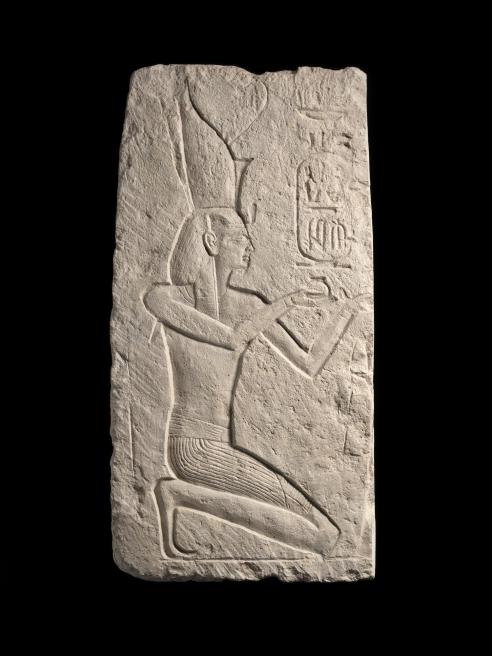

Throughout human history, many sculptures have been carved in raised relief, which means the background is removed to leave the subject (e.g. people, animals, mythological scenes) projecting forwards. Carving in raised relief can be almost three-dimensional and may even have some elements partially detached from the background, such as the Parthenon Marbles, or be very low, such as the Queen’s face on a coin. Raised relief carving can also be used to decorate stones used in building construction, such as in medieval European cathedrals, or ancient Egyptian tombs or temples.

Removal of a large amount of the surface of the stone is labour-intensive though, so stonemasons generally use softer stones, such as limestone or sandstone. This also allows more detail to be added, and ancient Egyptian wall reliefs were sometimes painted as well. Raised relief sculpture in ancient Egypt was typically displayed inside, lit by natural light from doorways, windows and openings in the roof.

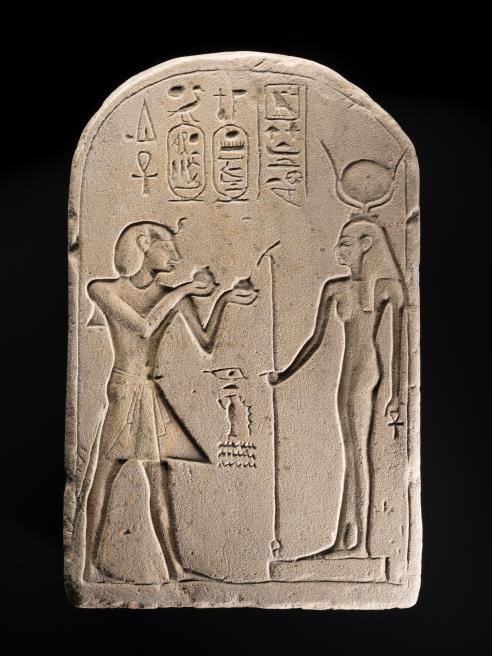

Sunk relief carving

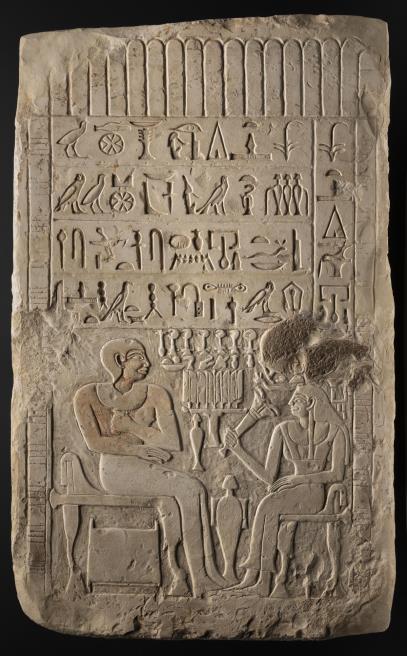

Another type of relief carving is very specific to ancient Egypt, and is rarely found elsewhere. In sunk relief, the three-dimensional carving is cut into the surface of the stone, often deeply, frequently with simplified shapes and designs. As less stone needs to be removed, a harder stone such as granite could be used. This technique lends itself particularly well to carving hieroglyphs. The deep carvings also show up particularly well on external walls in the bright African sunshine, with shadows emphasising the designs. This style of carving was favoured by the controversial pharaoh Akhenaten, and became the dominant technique after his reign (c.1353–1336 BC); see examples below. Sometimes sunk relief carvings could incorporate raised relief details inside the figures, to include details within a dark shadow outline.

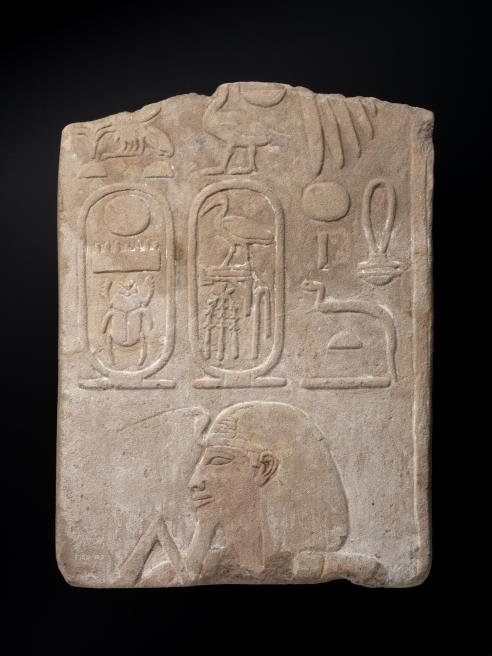

Examples of sunk relief sculpture on display in the gallery include reliefs and stela (commemorative or votive tablets), as well as the majority of hieroglyphs accompanying raised relief carvings. One particularly topical example of this technique is either a student’s practice piece or sculptor’s demonstration piece, used to show students how to depict the standardised image of King Akhenaten. Below the chin you can see circular drill marks showing different stages in the decoration of the crown.

Other examples in the gallery combine both figurative raised relief carving with sunk relief hieroglyphs. Whether raised or sunk relief, these carvings would originally have been brightly coloured by over-painting. We chose not to use paint as it would be quickly worn away by the hands of many visitors.

Choosing the design, materials, size and artist

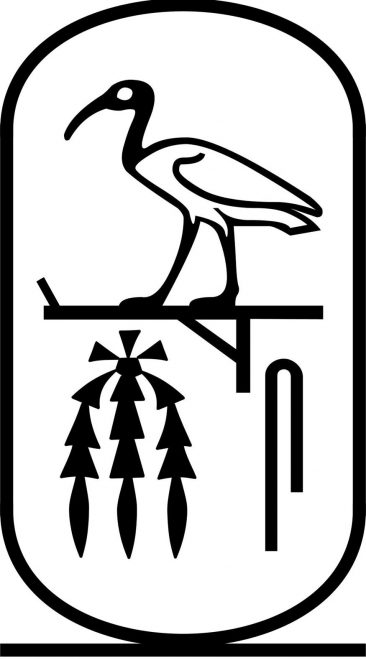

Having chosen to showcase these two stone carving techniques, we had to choose the designs to be depicted. Hieroglyphs appear all over ancient Egyptian sculpture carved using both techniques, so they could be easily compared, especially if names with similar characters were chosen.

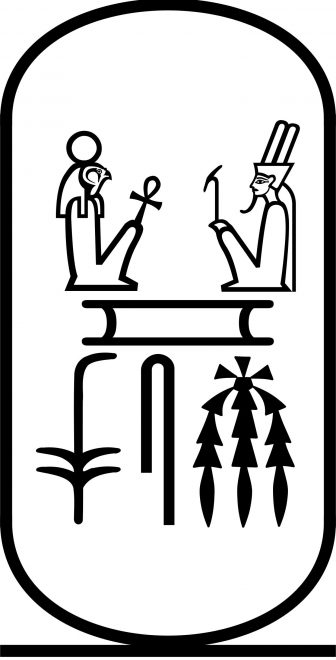

A raised relief fragment of King Thutmose III in our collection has a nice, clear depiction of his name, surrounded by a cartouche, or an oval with a horizontal line below. A cartouche is actually another hieroglyph itself, meaning ‘eternity’, and was used to both indicate a royal name, and offer protection to the owner in both life and death.

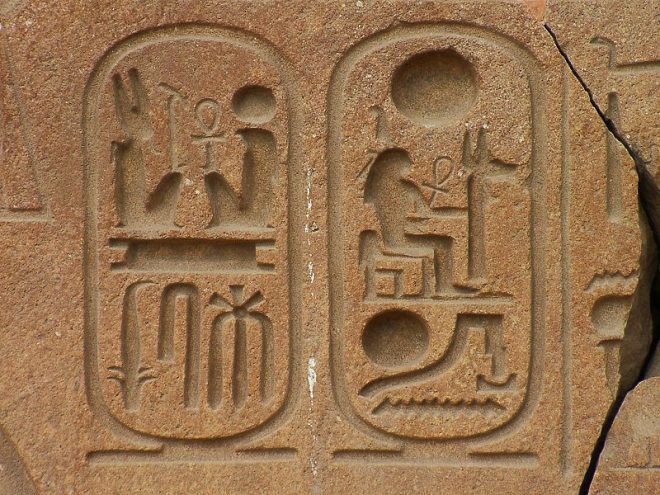

While our collection includes many examples of hieroglyphs carved in sunk relief, the examples of cartouches weren’t carved as clearly. This relief fragment of the great King Ramesses II features his cartouche in sunk relief, but it’s not as legible.

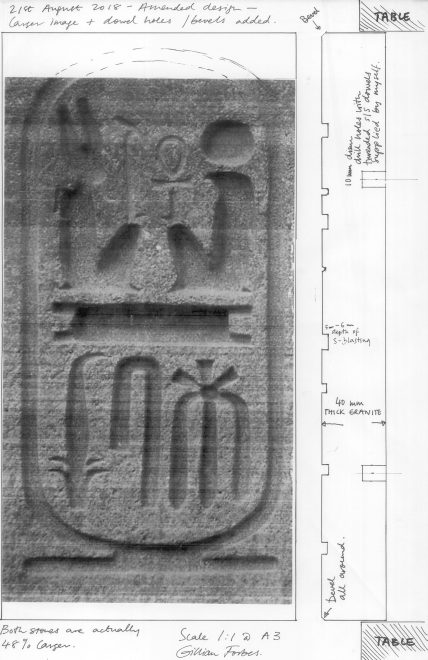

Luckily Ramesses II had his name carved many times on numerous buildings, including this example from the royal city of Tanis.

Looking closely, you can see two of the same hieroglyphs in Thutmose and Ramesses’ names; the bundle of three pendant fox skins pronounced ‘ms’, and the crook-like folded cloth representing the letter ‘s’. These hieroglyphs spell out ‘born of’: Thutmose, meaning ‘born of the god Thoth’, and Ramesses, meaning ‘born of the god Ra’. So these were two good names with which to compare the different techniques.

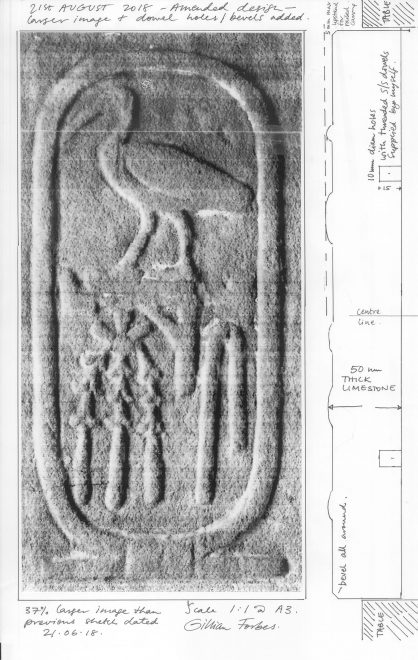

In terms of choosing exact materials, we knew raised relief was mostly carved in softer stone such as limestone, and sunk relief generally in harder stone such as granite. To choose the exact materials, we thought it best to consult an expert, so after researching several local stonemasons online, I asked them to put forward suggestions as to how they would tackle the project. We had a good response, but eventually decided to work with Gillian Forbes, who has an excellent portfolio of both three-dimensional carving and sunk lettering. You can also find her work on the Scottish Parliament Building at Holyrood.

Gillian had a nice bit of limestone already in her workshop, and she knew where to source some pink granite up in Aberdeenshire, which resembles that mined around Aswan in Egypt. Following discussions between her, curators, external designers, and project managers, we agreed on the final size, scale, display table, mounting system, and interpretive text for the carvings.

Gillian drew her designs using photographs of our object and the Tanis carving, and also ‘vectors’ or simplified diagrams of the hieroglyphs.

The final design for the raised relief carving

Today’s stonemasons still use traditional mallets and chisels, although the metal blades are made of much stronger materials than the relatively soft copper that the ancient Egyptians used. To save time though, for our project it was more efficient to work the sunk relief carving in granite using modern sand-blasting equipment. As the work-in-progress photos show, Gillian’s approach to the limestone carving was much the same as that of an ancient stonemason. The design is drawn, the outlines are ‘blocked out’, and the background cut away, before the details are added later.

It was very exciting to see photos of the finished carvings, and to finally get my hands on the pieces themselves. They are beautifully carved, and have greatly contrasting textures. They should cope well with the effects of being touched by millions of museum visitors, for years to come. Hopefully they will inspire people to look differently at our many carved stone monuments on display, and see if they can guess whether they were displayed indoors or outdoors depending on the stone and the style of carving.

Thanks to the willing workforce, this construction project is complete! I’m sure Ramesses II and Thutmose III would be very pleased indeed to have their names still recognised and commemorated almost three and a half millennia later.