Over the past six months I have worked on a project to conserve works on paper for the new East Asia gallery, due to open at the National Museum of Scotland in early 2019.

As Assistant Paper Conservator, I have encountered beautiful and interesting objects, ranging from Chinese pith paintings and ceremonial costume paintings on silk to Japanese woodblock prints; it has been the prints that have formed the basis for most of my work and treatment.

In total I have conserved and prepared for display over 40 Japanese woodblock prints, depicting a range of subjects such as Kabuki actors, Samurai and Japanese landscapes, with the images being presented as single, diptych and triptych prints. The prints are all vibrant and rich in colour. In order to minimise any potential fading from light exposure, only a selection of the prints will be displayed at any one time, and rotated at six-month intervals.

It has been a fantastic and varied collection to work on, and I have been hard pressed to pick my favourites. But, in the spirit of our current summer blockbuster exhibition Rip It Up: The Story of Scottish Pop, I am going to count down my Top 3 ‘Pick of the Prints’, and explain the treatment that was undertaken.

Straight in at no. 3, there’s something fishy going on….

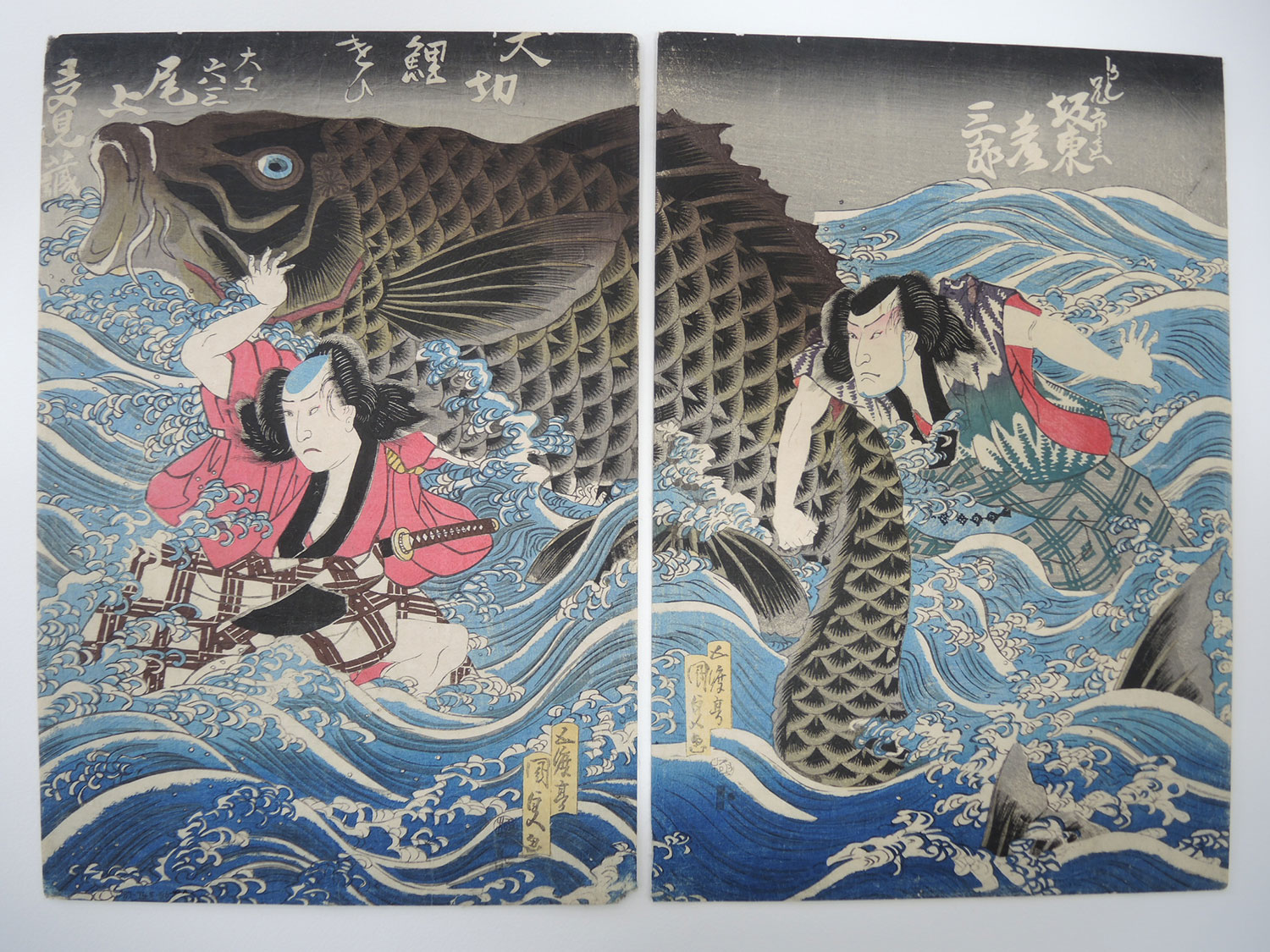

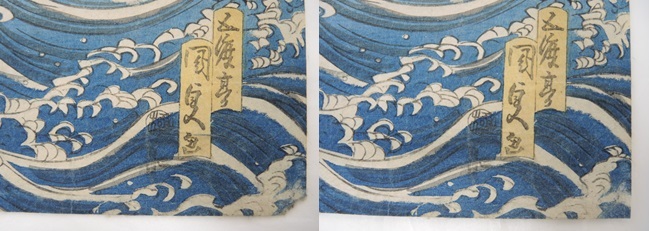

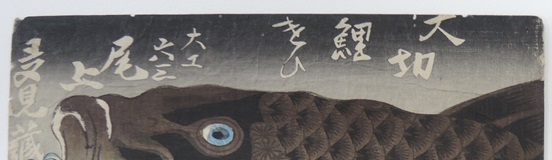

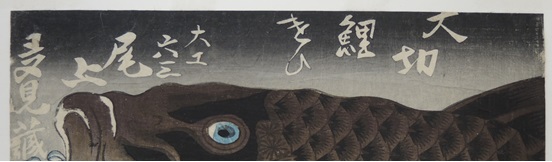

This Japanese woodblock diptych, designed by Utagawa Kunisada in 1830-1835, depicts two Kabuki actors struggling against a giant carp, and it is this striking and dramatic imagery which makes it one of my favourite prints.

The prints themselves had several small holes along the top edge – probably due to insect damage – as well as a missing corner. Both for aesthetic and practical reasons, and to stabilise the print so that it can be safely handled and displayed, I took the decision to infill the losses using a compatible Japanese tissue which was toned using watercolours and pastels. The infill was cut to the size of the area of loss and, once positioned, was secured using wheat starch paste; a treatment which can be reversed in the future if required. The result is that the losses are less visibly distracting when the print is on display, and the giant carp can take centre stage!

Counting down to no. 2, we have….

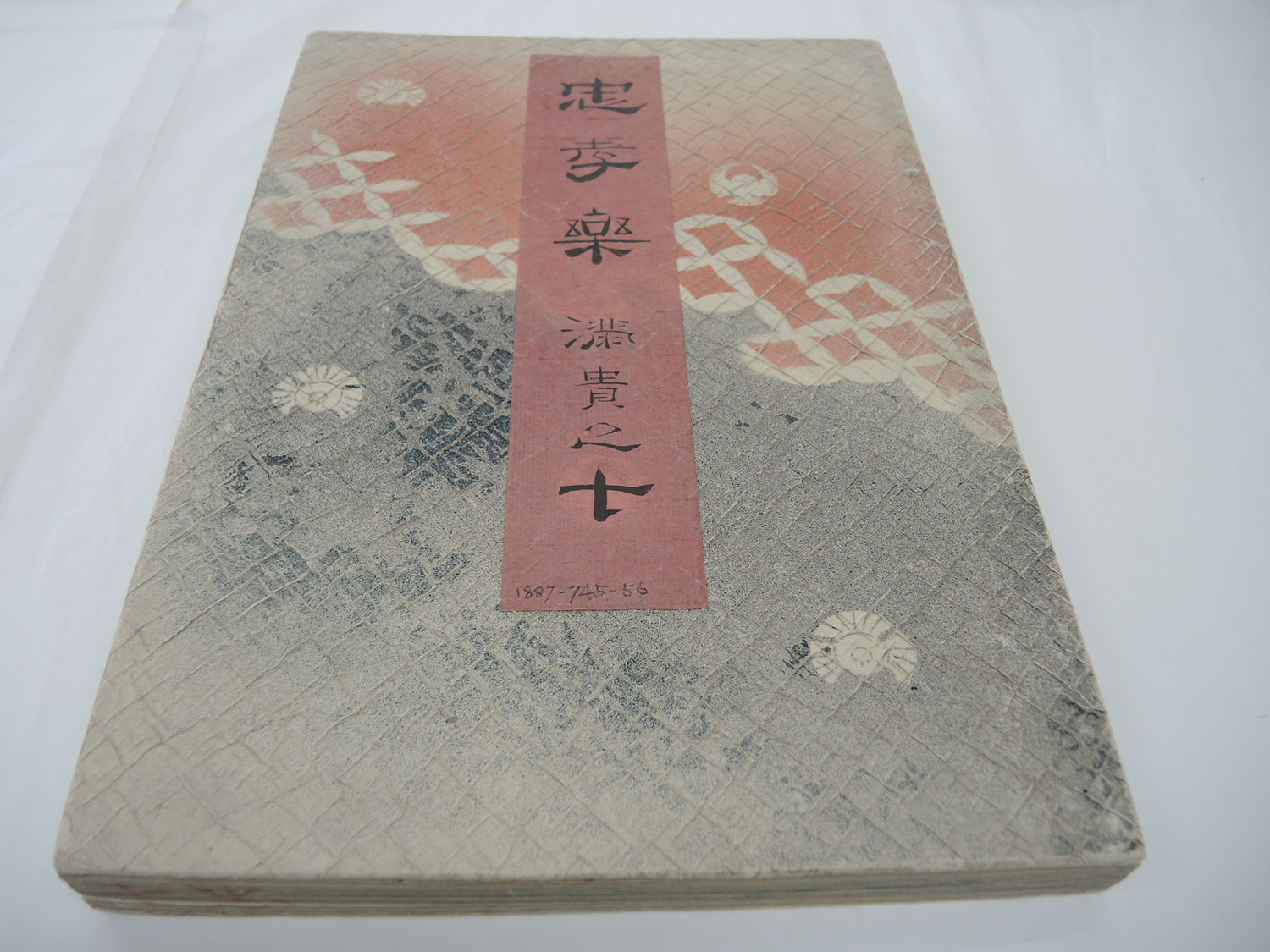

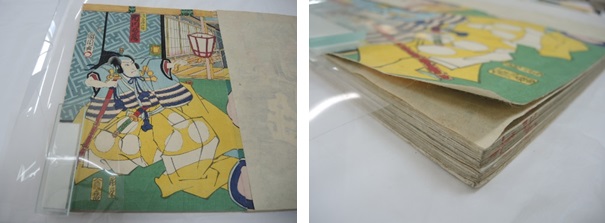

A triptych by Toyohara Kunichika from 1864, depicting a scene from a Kabuki play on the story of Raikō and the Earth Spider. This print has made it into my top three not only for its vibrant colours and rich details but also because it has allowed me to undertake a treatment I hadn’t had the opportunity to use much before, namely using enzymes. Although the majority of the prints were loose there were several, like the print below, that were adhered into albums.

The first consideration is whether to extract the print from the album or not, and I considered several factors before deciding on a treatment plan. In the album, it was attached to the prints on either side, creating a concertina effect, thus making the prints difficult to handle and display safely. The prints would also face each other when the album was closed, increasing the risk of abrasion or transfer of colour.

The decision, therefore, was taken to remove the prints from the album. To do this I used enzymes, specifically the Albertina Kompress, which uses an amylase poultice to break down starch-based adhesives. One of the main benefits of using this method is that it controls the amount of moisture that is used. This is particularly important when one needs to apply the amylase poultice directly onto the coloured inks, some of which may potentially be moisture sensitive.

After applying the enzyme along the edges where the print was adhered into the album, I was able to carefully separate and remove the print and subsequently conserve, hinge and window-mount it for display. Documentation is a big part of any treatment process, so I have photographed and noted the condition of the print, as well as labelled the album so that it is clear where and how it had been housed, making the process reversible if required.

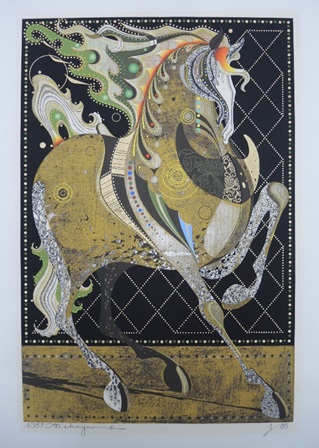

And at no. 1, we have the mane attraction…

Whilst most of the Japanese woodblock prints date from the 19th century, there is a series of more contemporary ones, including this woodblock print by Japanese artist Nakayama Tadashi titled ‘Dancing Stallion’ (1987). Although the print did not require much treatment – primarily hinging and mounting – the metallic silver and gold colours and bold forms make it one of the one most vibrant in the collection and, at over a metre in length, certainly the largest! It will definitely make an impact in the new gallery space and is one not to be missed.

It has been a fantastic project and a pleasure to work on such wonderful objects. You can find out more about the new galleries due to open in 2019 here, and discover more about Japanese woodblock prints in the museum collection here.

Our new galleries are supported by the National Lottery through the Heritage Lottery Fund.

We still have £125,000 left to raise to complete this final chapter of the Museum’s transformation – will you be a part of it with a gift today?

Find out how you can be part of the story at www.nms.ac.uk/transform