Prior to moving our bird collection at the National Museums Collection Centre, much planning and preliminary work was carried out in early 2014. During this process, the contents of all cabinets containing bird skins and some older cupboards were logged. A few old drawers contained miscellaneous skins that had been repaired in the 1960s; one in particular caught my eye.

The museum label of this unregistered skin named it erroneously as a Twite Carduelis flavirostris (a small Eurasian finch) although it was actually a Pine Siskin Carduelis pinus, a North American finch.

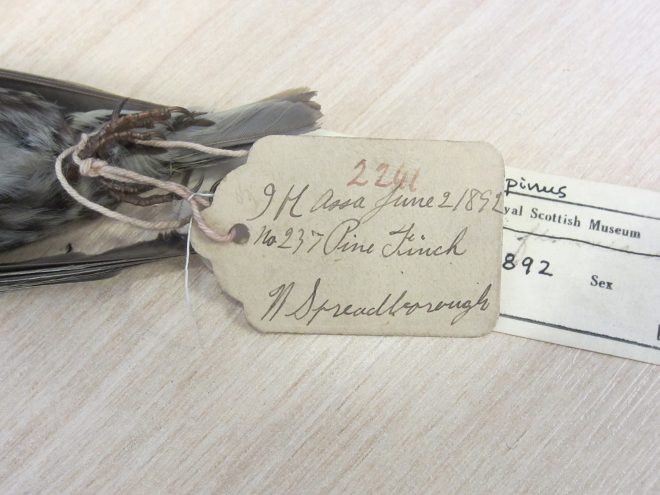

The collector’s label named it Pine Finch and it bore the date June 2 1892; also inscribed were two collector’s numbers No 237 and 2241. Additional inscriptions were I [or J?] H Assa and N [or W?] Spreadborough. Perhaps these were the collector’s name and the locality? Later, I accessed the ORNIS database, which holds information on five million bird specimens held by over 40 institutions, mainly in North America. Spreadborough as a locality yielded nothing, but as a collector the name William Spreadborough appeared in the results. This led to a list of hundreds of Spreadborough’s skins held at the Canadian Museum of Nature, Ottawa. I emailed Michel Gosselin, the CMN’s curator of birds, enquiring about Spreadborough’s collections and asking if there was any record of the Edinburgh skin having been formally exchanged.

He confirmed the siskin was one of William Spreadborough’s birds, a specimen from his 1892 expedition to Assiniboia (now part of Saskatchewan); the inscription “I H Assa”, at the top of the label, referred to “Indian Head, Assiniboia”.

Spreadborough’s skins of 1892 were catalogued sequentially according to their field numbers, and many were already missing in 1911, including No. 237. Michel wrote:

“It is unlikely that they were sent on exchange, as our institution was not collecting foreign material at the time, and these specimens were certainly not sent out by Spreadborough himself, who appears to have been a devoted field collector, unlikely to have done anything that he was not instructed to. Interestingly, this specimen is mentioned in [John] Macoun’s Catalogue of Canadian Birds. Spreadborough reports two siskin specimens from Indian Head, but we have none.”

The Catalogue read:

“On June 2nd, 1892, this species was common on the shore of Deep lake, near Indian Head, Sask., where they were feeding on some small insects near the water, two were shot and their stomachs were full of insects.”

This was excellent information on the skin; but hints of tragedy turned my attention to Spreadborough himself. Later I checked on a short profile published in 2002 by historian Bill Waiser in The Beaver.

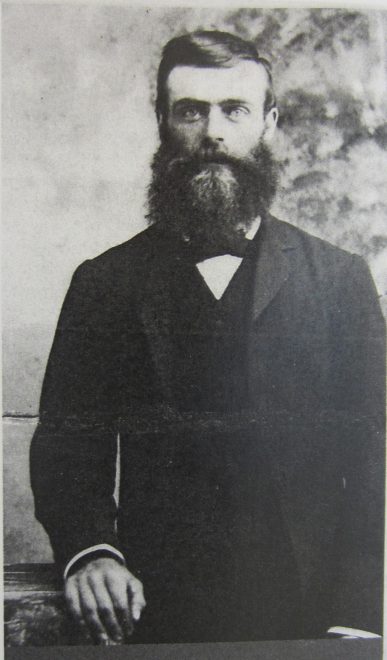

Waiser had written a book on Professor John Macoun’s natural history work and had become intrigued by the references to Spreadborough, who had joined John Macoun and his son Jim as collector in 1889, spending the next 30 years gathering specimens in remote regions of Canada. Spreadborough’s young wife had died in childbirth shortly before he joined Macoun’s expeditions.

Waiser continued:

“But tragedy continued to mar his life. While riding in the back of a wagon in the Indian Head area in 1982, his specimen gun accidentally discharged and killed the driver; for many years thereafter, he looked after the man’s widow and eventually married her.”

Despite Macoun’s efforts to recruit Spreadborough to the permanent survey staff, he was always only given temporary summer employment. When Jim Macoun died in 1919, Spreadborough lost interest in fieldwork and thereafter worked for the city of Esquimalt, British Columbia. Waiser finished his article by quoting a letter in the Percy Taverner correspondence at the Royal Ontario Museum:

“There, I found a letter that related Spreadborough’s tragic death the day he retired in 1931. ‘The feeling of uselessness was too much for him,’ Taverner told a friend, ‘and he hanged himself in his little workshop leaving a note for his wife that they had not saved enough for two; rather than live on in poverty, it was better that he should pass out. Too bad, poor old Spreadborough.’”

Poor old Spreadborough indeed! My earlier glee was replaced by gloom and I returned to my office and stared at the little finch for several minutes reflecting on the strange tale. Remarkably, the second Pine Siskin collected on 2 June is also here. I doubt I’ll ever find out how and when these skins came to Edinburgh.