The National Museums Scotland Research Library may rightly be called one of Edinburgh’s hidden gems. And, as the library boasts a vast array of interesting collections, it is well worth searching out.

My story within the Research Library began last January, taking up a work placement as part of my MSc in Book History and Material Culture at the University of Edinburgh. Eager to embark on a career in libraries and archives upon graduation, I have been keen to learn about the process involved in recording and cataloguing books and other archival material. Luckily, I was presented with an exciting opportunity to map the pre-1800 book collections of the Alexander Henry Rhind Bequest. The various books I have encountered over the course of this project have piqued my interest in the man behind this collection, and a brief introduction of his life is therefore in order.

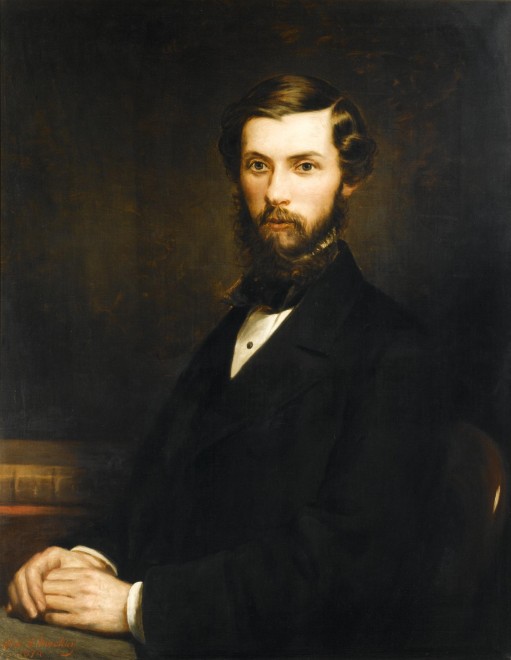

Born in Caithness in 1833, Alexander Henry Rhind developed a keen interest in the history of his native region. Having studied Scottish History at Edinburgh University, he became one of the foremost archaeologists of his time. His work was characterised by the careful mapping and measuring of his excavation sites, whose importance for ‘their instructive capability as an intact group’ he greatly emphasised.[1] Although this rigorous approach to archaeology was not uncommon in Scotland at the time, the exemplary quality of his work made him a Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland at the unconventional age of nineteen.[2] His dwindling health, however, forced him to relocate to warmer climes, opting to focus predominantly on Egyptology within his archaeological endeavours. He travelled extensively in search of intact burial sites, an endeavour in which he happily succeeded towards the end of his life.

Alexander Henry Rhind’s promising career was unfortunately not to last. But although he died in 1863 at the early age of twenty-nine, in his short lifetime he contributed greatly to the field of archaeology, both Scottish and Egyptian. He also donated extensive archaeological collections to the National Museum of Antiquities of Scotland which would later become part of National Museums Scotland.

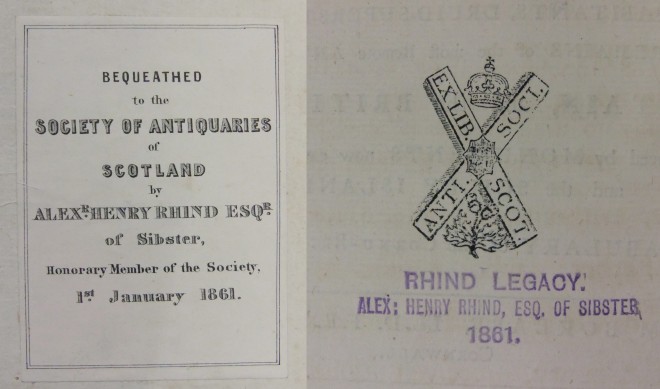

Upon his death he bequeathed his entire library to the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, along with strict instructions that it should ‘be added to and preserved with the library of said Society, but not kept apart or in any way distinguished except by the insertion of a book-plate shewing them to have been a bequest.’[3] In the end, for reasons unknown as of yet, only a select few of his books were to receive such a bookplate (although it has been suggested that the poor overworked librarian responsible for its execution may have been slightly daunted by the monumental task of supplying bookplates to all 1,500 books). Instead, some were given a stamp, whereas most others would be denied any sign of their link to Rhind’s former library at all.

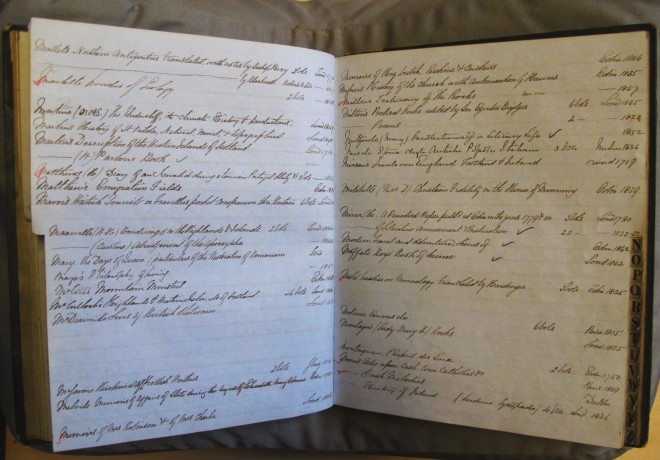

As such, in order to locate these books, I had to rely on Rhind’s own handwritten catalogue, a plain bound volume that had long lain hidden away in one of the library’s cupboards. Lacking a name or a signature, Rhind’s catalogue had for years remained unidentified, and it was only a few months ago that – through the discovery of a small note scribbled in the front –it could be securely linked to his bequest.

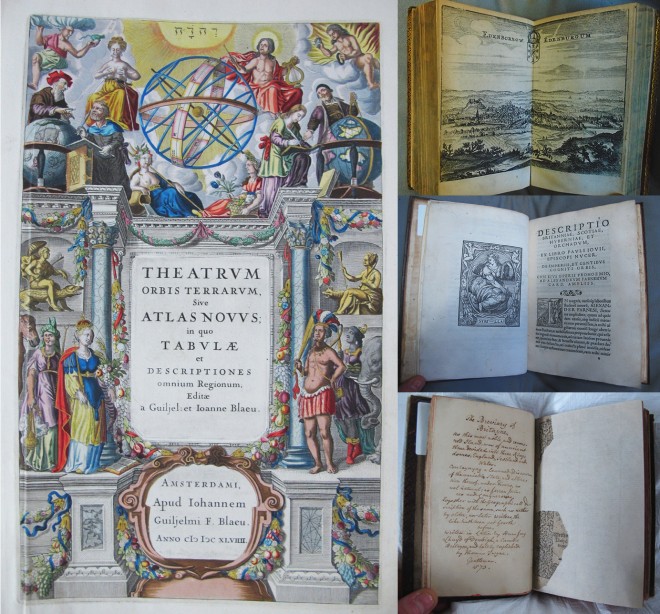

Having deciphered the individual entries and worked my way through the hidden corridors of the museum, I descended into the library’s special collections store. Working behind the scenes of such a large repository is always a welcome and wonderful experience, and – having always had a fondness for old books – this store room, with its vaulted ceilings and vanilla smell of ancient paper, makes it one of most interesting I’ve come across.

After collecting all the books needed for the day, I emerged from the repository to start the actual act of cataloguing. Examining every book individually, I recorded as much information as I could possibly find. This included not only title, author, and publication information, but also a detailed physical description of the tome in question, Rhind’s donorship, and any other marks of provenance (which occasionally proves difficult due to previous owners’ horrid handwriting!).

When the library has multiple copies of any particular book, finding those attached to the bequest can be relatively easy when Rhind’s copy contains a stamp, or the other copy holds a bookplate that identifies its independent donor. However, when both lack such provenance marks further detective work is required. The museum archive holds records of historical donations, with most information found in the bound volumes containing the Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland. Although sometimes these mysteries remain unsolved, often new pieces of the puzzle are discovered. But never knowing what might be discovered next makes working on this project such a worthwhile experience.

Linking Rhind’s name to the books in his bequest in the National Museums catalogue might open up new avenues for research into his life and his academic ventures and interests, allowing him to be more fully recognised for his archaeological contributions.

Bibliography

Irving, Ross, and Margaret Maitland. “An Innovative Antiquarian: Alexander Henry Rhind’s Excavations in Egypt and His Collection in the National Museums Scotland.” In Every Traveller Needs a Compass: Travel and Collecting in Eqypt and the Near East, edited by Neil Cooke and Vanessa Daubney, 85-100. Oxford: Oxbow, 2015.

Stuart, John. Memoir of the Late Alexander Henry Rhind, of Sibster. Edinburgh: Printed by Neil and Company, 1864.

(Both books are available in the National Museums Scotland’s Research Library)

[1] Irving and Maitland, “An Innovative Antiquarian: Alexander Henry Rhind’s Excavations in Egypt and His Collection in the National Museums Scotland,” 95.

[2] Ibid, 89.

[3] Stuart, Memoir of the Late Alexander Henry Rhind, of Sibster, 56.