Does your favourite jumper have a hole in it? Seems a shame to get rid of a lovely piece of clothing because of a little tear, right? How about mending it! Senior Curator of Historic Textiles Helen Wyld talks us through some of the historic repairs in our textiles collection. You never know, it might inspire you to pick up a needle and thread!

Mending and re-using clothes is seeing a revival, driven by a desire for a more sustainable culture, an interest in craft and the handmade, and, perhaps, the time many of us spent at home during the pandemic. Mending is gaining new ground today, with visible repairs appearing on everything from ripped jeans to worn out jumpers. But our textile collections show that mending was a way of life in past centuries. And not just for the poor. Historically, clothing and textiles have been highly valued possessions, too costly to throw away when they became worn out.

Gunnister Man

Among the most poignant items of clothing in our collection are those found on a body discovered in a peat bog near Gunnister in Shetland. The individual was subsequently christened “Gunnister Man”. He probably died in around 1700. While we have many examples of elite clothing from the 17th century, it is extremely rare to find the dress of a person of more moderate means.

Gunnister Man was probably a trader and was found with a bone spoon and three coins in his pocket: one Swedish and two Dutch. They were kept in a knitted purse. His woollen clothes have been heavily mended. His jacket is patched and lined with different pieces of cloth. Two buttons are replaced with cord. A hole in his glove is patched with a coarse fabric. And a tear in his shirt is inexpertly mended with a large tuck. His rough stockings have been reinforced at the soles with large patches, partly to cover existing holes and partly, we might guess, to add warmth.

The messy and ad hoc nature of these repairs suggests that they were made by the wearer himself, of necessity. This man could not afford new clothes and was not a skilled mender but kept his clothes intact as best he could.

A pocket made by Miss Rolland of Burnside, Fife

Far more expert mending is evident on a woman’s pocket made in the early 18th century by a certain Miss Rolland of Burnside in Fife. In this period, women’s clothes did not have integrated pockets (a problem we still encounter today!). Women wore separate pockets attached to a band of cloth and tied around the waist, under their skirts. Women of all classes wore pockets, and they kept anything from money to sewing equipment inside them. Miss Burnside’s pocket is made of homespun white linen, embroidered in wool with pink and blue flowers. On closer examination we can see that the pocket has been well used. A number of splits around the opening have been mended with carefully applied patches on the reverse, attached with tiny, regular stitches. Probably by Miss Burnside herself. She must have continued to use the pocket over a number of years.

This kind of skill was expected of girls across a range of social classes. Miss Burnside may have learned to sew from her mother or another woman in her family, or from a local schoolmistress. The pocket seems to have been treasured even after Miss Burnside’s death: it entered our museum with a note attached to it telling us that she made it in the year 1733.

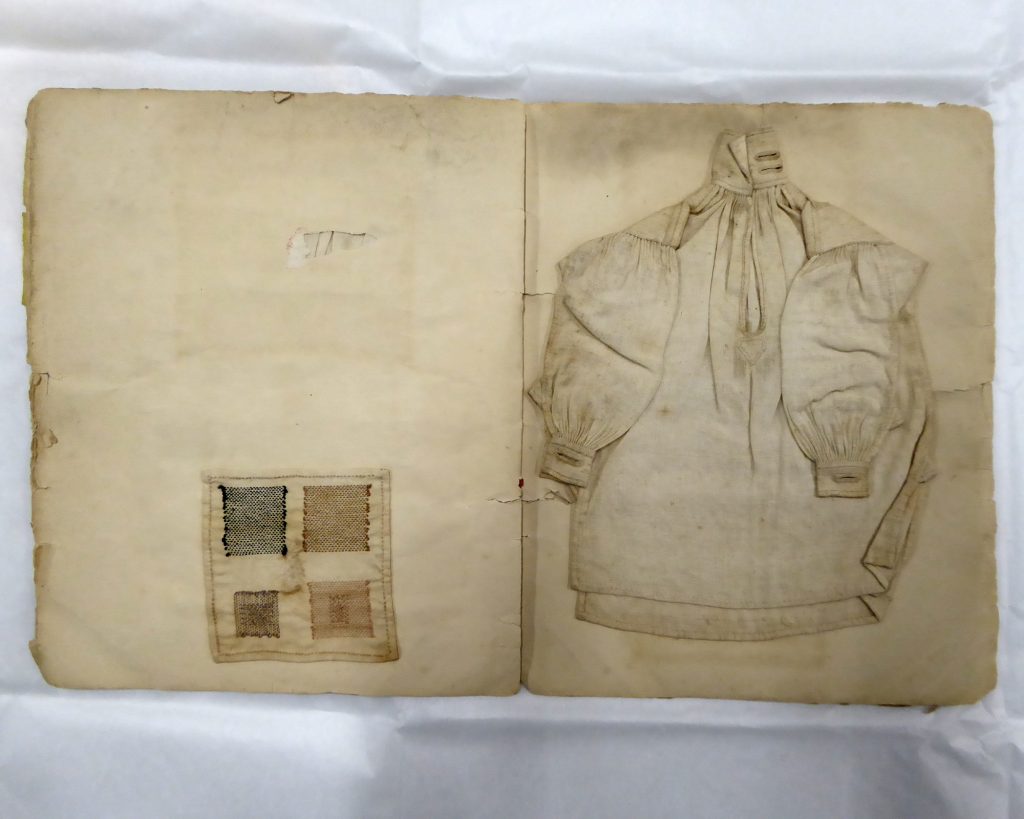

A collection of plain sewing samplers

A remarkable book, with the handwritten title “Hannah Grindley 1st Class Examination 1838”, shows us some of the mending techniques being taught to girls by this date. The book contains a series of beautiful sewing samplers, and a complete miniature shirt, demonstrating a range of skills, including hems, tucks, frills and buttonholes.

Equally essential are the mending techniques. Hannah’s book includes a sampler with needle darning in four colours, and carefully edged patches. These are executed with coloured threads to display the neat stitching, but when applied in the real world, they would have been made using threads matching the original fabric. While visible repairs are prized today, historically menders wished their work to go unnoticed.

Hannah’s book probably follows one of the published instruction manuals that began to appear from the 1830s onwards, but darning samplers had been common before this. Our collection includes samplers of needle darning imitating a range of different textile weaves. These complex techniques would have allowed women to make invisible repairs to items such as linen tableware, tweed and checked cloth. A later collection of school samples includes knitted mending techniques. These were essential for socks and jumpers worn out at the heel or toe.

A pair of knitted long johns from Fala Dam

Mending and making clothes continued to be a way of life for many in Scotland during the twentieth century. A collection acquired by our museum in the 1960s, the contents of a farmhouse at Fala Dam in East Lothian, provides a remarkable insight into the everyday mending and making of one family.

The collection includes a range of sewing equipment: needles, thread, elastic, buttons, as well as knitting needles, crochet hooks and children’s needlework samplers. Many of the garments from this collection seem to be home made, while others show signs of repeated mending. Most notably a pair of machine-knitted long johns! They have numerous areas of neat needle darning and must have been worn over a number of years to keep the wearer cosy on chilly winters’ mornings on the farm. Overall, the Fala Dam collection includes the work of at least three generations of handy knitters and stitchers.

As we can see from our collections, the skills being revived today are far from new. With the mass production and increasing affordability of clothing from the 1960s onwards, skills like sewing, knitting and darning became less common. But today’s concern for sustainability means we can find new value in historic practices that were once commonplace.

Further reading

Barbara Burman and Ariane Fennetaux, The Pocket: a Hidden History of Women’s Lives, 1660-1900, New Haven 2019

Audrey Henshall and Stuart Maxwell, ‘Clothing and other articles from a late 17th-century grave at Gunnister, Shetland’, Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, 1951-2, pp. 30-42

Naomi Tarrant, “Remember Now Thy Creator” : Scottish Girls’ Samplers, 1700-1872, Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, 2014