The Carolina parakeet is the poster bird for our Audubon’s Birds of America exhibition. Assistant Curator of Vertebrate Biology, Zena Timmons, explores the decline of this bird species, information revealed by our specimens and how an extinct species can be recreated through taxidermy.

The Carolina parakeets (Conuropsis carolinensis) painted by artist and naturalist John James Audubon burst with colour, energy and charisma. They appear so animated, perched at all sorts of angles, scratching themselves and frolicking. They look so alive! Carolina parakeets were the only endemic parrot species in North America and considered widespread. In 1939, the species was officially declared extinct.

The following extract is from Audubon’s Ornithological Biography. Audubon first wrote about the declining numbers of Carolina parakeets in response to the parakeets’ tendency to eat farmers’ crops.

“Do not imagine, reader, that all these outrages are borne without severe retaliation on the part of the planters. So far from this, the Parakeets are destroyed in great numbers, for whilst busily engaged in plucking off the fruits or tearing the grain from the stacks, the husbandman approaches them with perfect ease, and commits great slaughter among them. All the survivors rise, shriek, fly round about for a few minutes, and again alight on the very place of most imminent danger. The gun is kept at work; eight or ten, or even twenty, are killed at every discharge. The living birds, as if conscious of the death of their companions, sweep over their bodies, screaming as loud as ever, but still return to the stack to be shot at, until so few remain alive, that the farmer does not consider it worth his while to spend more of his ammunition. I have seen several hundreds destroyed in this manner in the course of a few hours, and have procured a basketful of these birds at a few shots, in order to make choice of good specimens for drawing the figures by which this species is represented in the plate now under your consideration.”

Carolina parakeets gathered in flocks of a few hundred or more and their diet consisted of nuts, fruit and seeds, as well as cultivated crops. Written descriptions of the time suggest that crops were quickly decimated by visiting parakeets. Large, noisy flocks deterred potential predators but made them an easy target for farmers and hunters.

Farmers reached for their guns to try and protect crops, others shot the parakeets for food or sport and collected them for the pet trade, and their vibrant plumage was in demand for use in fashion items of the time. Habitat clearing for agriculture and industry also reduced suitable nest site availability making it difficult for the parakeets to reproduce and for their numbers to bounce back.

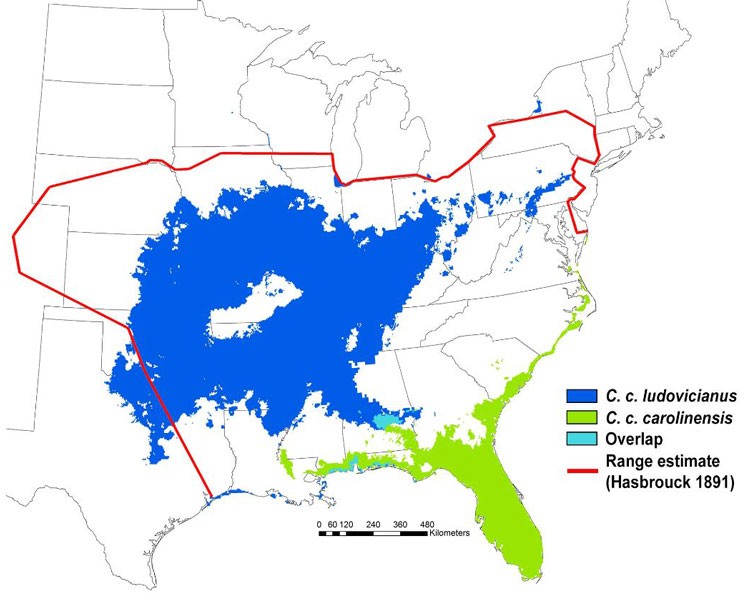

Persecution and habitat loss undoubtedly contributed to a significant reduction of Carolina parakeet numbers. Despite this, some birds did survive, even after the species was declared extinct. Current research has identified that there were two separate subspecies of Carolina parakeet: the eastern subspecies Conuropsis carolinensis carolinensis and western subspecies Conuropsis carolinensis ludovicianus.

Their distribution ranges were smaller than expected, which could mean that the numbers of parakeets were much lower than first thought. The latest verified sightings vary from 1910 for the western subspecies and 1944 for the eastern. Florida and the Carolinas provided refuge for the last parakeets, but those populations mysteriously died out.

Although we don’t know why and exactly when the last of the Carolina parakeets vanished from the wild, bird study skins held in museum collections may offer us some further clues. Study skins provide visual and morphometric (size and shape) information, such as plumage differences and wing and bill measurements, as well as geographic data as to where the bird was found and when. Yet they also hold a wealth of unique information that can’t be seen with the naked eye.

On a molecular level, data obtained from a tiny sample of skin or feather can offer important insights. By analysing these types of samples, we can determine what some birds were feeding on and then deduce migration patterns, identify their species and sex, if they were affected by disease, and extract their DNA. All this additional information helps paint a bigger picture (not unlike Audubon) about a bird’s life which could help us in the future to understand what happened to it and the rest of its species. Current bird conservation projects can also benefit from these findings.

Because of the fragility and rarity of our own Carolina parakeet study skins, they couldn’t be put on display in our new exhibition. As a result, the Carolina parakeet mount in the Audubon’s Birds of America exhibition is a ‘taxidermy copy’ made by Derek Frampton. Derek is a taxidermist who specialises in recreating extinct species. Two ring-necked parakeet (Psittacula krameri) skins were used to make it.

To reproduce an accurate replica, Derek obtained precise measurements and reference images of Carolina parakeets to work from. A mannequin was hand carved from balsa wood to provide the main structure onto which the skins were attached. The head was created from a cast of a Carolina parakeet skull and beak, and the head feathers were from a lutino (yellow) phase ring-necked parakeet. Derek then carefully reconfigured and shaped the tail and wing feathers and tinted them to match a Carolina parakeet’s plumage. Tinting parakeet feathers is a difficult process. Because the colour is structural, they reflect light in a different way to feathers that are pigmented.

If you are able to visit Audubon’s Birds of America exhibition, take a closer look at this specimen. Although not a “real” Carolina parakeet, the actions that contributed towards the demise of this charismatic species were all too real. And similar actions are negatively impacting bird species all over the world today.

Audubon’s Birds of America is on at the National Museum of Scotland until 8 May 2022.