A recent spectacular find on the Isle of Skye shines new light on pterosaurs of the Jurassic period. Our Keeper of Natural Sciences Nick Fraser tells us more about this discovery, Skye’s fossil riches and the people bringing them to light, both in the past and today.

Perhaps best known for idealistic romanticism, an ancient toothy dragon rather shatters this image of the Isle of Skye. The discovery of a remarkable new fossil reptile paints an alternative vision for the island. Mysterious moors and mountains, shrouded in mist, give way to a world of lush vegetation and temperatures more in keeping with the tropics.

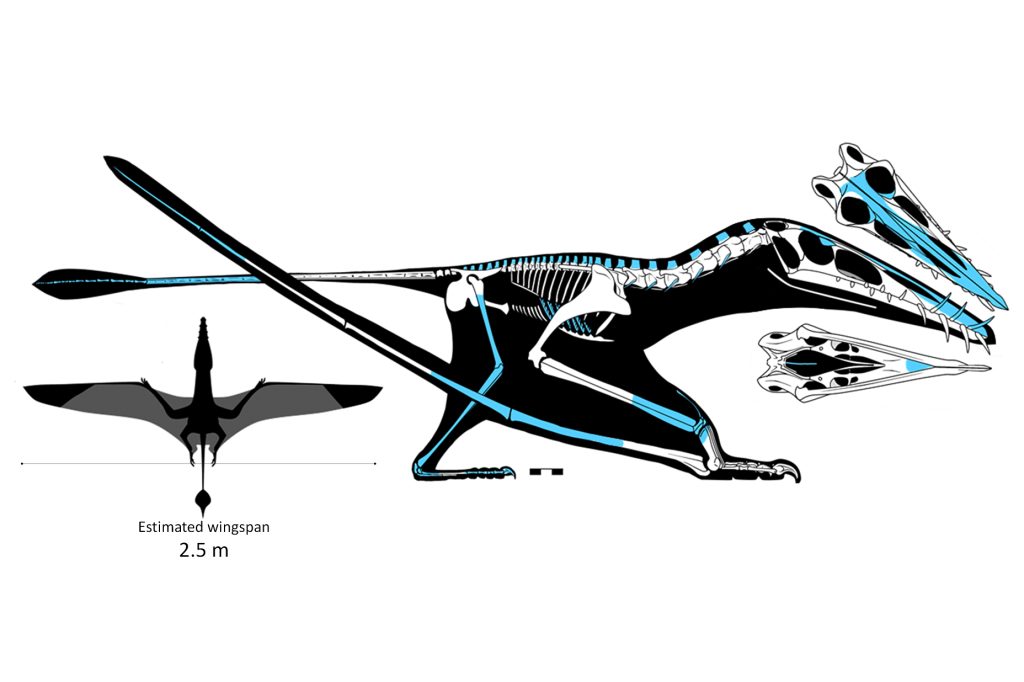

Inhabiting this world 170 million years ago were a variety of dinosaurs, along with their flying cousins, the pterosaurs. Dearc sgiathanach (pronounced jark ski-an-ach) is a completely new genus of pterosaur represented by a newly described fossil from Skye.

The so-called Great Estuarine Group (Jurassic) of the Inner Hebrides has been known since the mid-1800s and Scottish geologist Hugh Miller’s visits to Eigg. Since then, interest in the Jurassic rocks has been sporadic and the rather daunting cliff outcrops have proved reluctant to give up the secrets they hold of times past.

Beginning in the 1960s, the determined efforts of people like John Hudson (University of Leicester) and then Michael Waldman and Bob Savage (University of Bristol) began to reveal the huge potential of Skye for yielding new insights into its own Jurassic Park. Their discoveries of small mammals were particularly significant and, many years later, these formed the basis of Elsa Panciroli’s doctoral studies. Read about Elsa’s work on fossil mammals.

But it was the uncovering of a dinosaur footprint in 1982 that really sparked widespread interest, especially in local resident, Dugie Ross. Dugie is a remarkable palaeontologist and knows the outcrops of fossil-bearing sediments like the back of his hand. He founded and runs the Staffin Museum and has helped to highlight the international importance of the Jurassic of Skye and its dinosaur remains.

It was the fossil mammal discoveries of Savage and Waldman that led to further field work at the beginning of the millennium. Led by Susan Evans (University College London) and Paul Barrett (the Natural History Museum, London), and supported by National Geographic, the pace of fieldwork picked up. Their discoveries included finds of sauropod dinosaur teeth along with the remains of small vertebrates such as salamanders, lizards and turtles.

In 2010, our own Senior Curator of Vertebrate Palaeontology, Stig Walsh, initiated further field studies on Skye with Roger Benson (University of Oxford). My own involvement in the research was triggered when my friend and colleague Steve Brusatte felt it was time to approach National Geographic once again. Weathering of the cliffs had resulted in the opportunity for further prospecting. And what a perfect setting for some larger-scale fieldwork! So began our more in-depth work with a variety of experts from around the UK, including Stig Walsh, Roger Benson, and Richard Butler (University of Birmingham).

On one of Steve’s trips in 2017, one of his students, Amelia Penny, noticed bone on the surface of the flat limestone platform on the beach. When she alerted other members of the expedition it soon became apparent this was the jaw of a pterosaur. This was a really big find. Without the rock cracking skills of Dugie Ross on hand, this may well have been just one more fossil lost to the sea’s erosive powers. But with Dugie’s surgical skills with a rock saw and a group of practiced field geologists, the pterosaur was cut from the rock and safely hauled off the beach before it could be lost to the depths.

Once back in the lab, the fossil become the focus of the PhD program for another student, Natalia Jagielska. Incredibly, much of her study was undertaken under Covid restrictions, yet her meticulous description and analysis of the fossil has provided new insights into life in the Middle Jurassic.

It seems we had previously underestimated the size of pterosaurs in the Jurassic. While perhaps not as large as some of the giants of the Cretaceous (which were the size of small aeroplanes!) Dearc still had a wingspan comparable with that of a Wandering Albatross, the largest flying bird in the world and not an animal to be readily trifled with.

Until now, the majority of key discoveries on Skye have been either isolated bones or articulated remains of smaller vertebrates. The announcement of the discovery of Dearc changes the picture and puts Skye on the map as one of the world’s most important places for Middle Jurassic vertebrate fossils. As well as this remarkable fossil, it is also wonderful to see the Jurassic of Skye launch the careers of some of the next generation of palaeontologists.