There are over 60 spinning wheels in the collection, the majority of them are Scottish, along with a small group of continental wheels.

Several of the Scottish wheels are stamped with a maker’s mark and sometimes with an accompanying place name. This is important because it illustrates that spinning was done from the outer Hebrides, Orkney and Shetland, throughout the mainland and down to Dumfries and Galloway.

There is also a collection of associated implements such as distaffs, carders, winders and spindles and whorls.

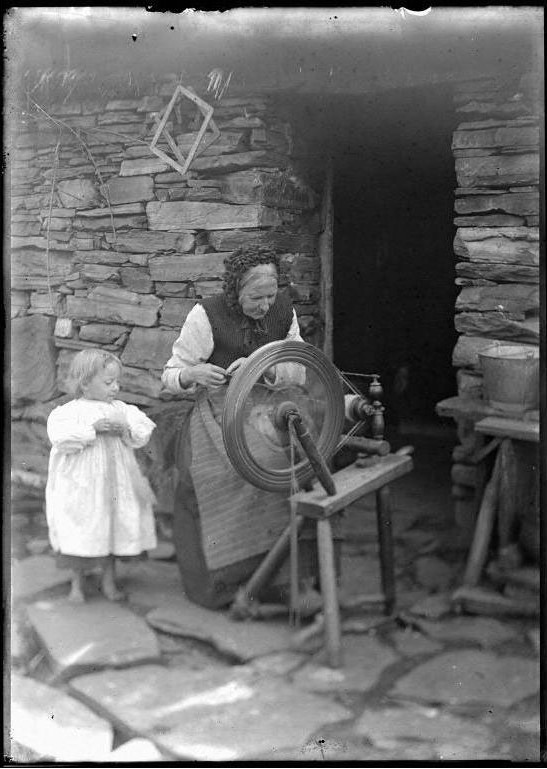

Spinning was a vital task in rural areas of pre-industrial Scotland. Wool would be knitted up into socks and other garments for the family or for sale, while linen thread spun from flax would be woven into fabric for different uses from household linen to sailcloth.

Most wheels were made by a local wood worker who would buy the drive wheel from a wheelwright and make and turn other parts before assembly. Many wheels were imported from Norway or brought back by fishermen or seamen returning from abroad, thus different styles were introduced and often copied.

The wheel we recognise today evolved from the perpendicular drop spindle and whorl which was used for thousands of years in most cultures all over the world. Yarn could be produced more easily and productively by placing the spindle horizontally and attaching it to a drive wheel by a band of cord. The drive wheel was either hand cranked or treadled. Also, this meant that spinning became a task where the spinner could sit at her wheel rather than multi task, for example, using her drop spindle when carrying peats or minding sheep or cattle.

Recognising various different types of Spinning Wheel

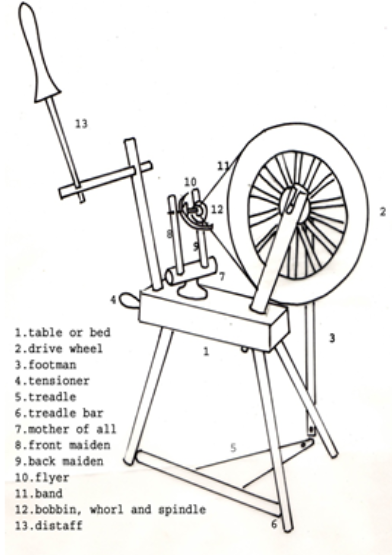

The main types of spinning wheel are known as: 1. Muckle, Great, or Walking wheel, 2. Upright wheel, 3. Horizontal or Saxony wheel and 4. Castle

A Muckle wheel where there is no treadle. The spinner turns the drive wheel clockwise by hand, teasing the fibres out by walking a few steps backward, stopping the drive wheel but starting it again this time anti-clockwise, thus winding the walked length of wool onto the spindle.

An Upright in all its various forms is a wheel where the spinning assembly consisting of the flier, spindle and bobbin are above the drive wheel and there is now a treadle.

A horizontal wheel or Saxony wheel where the drive wheel is on the spinner’s right hand side and the spinning assembly on the left. The bed is sloping slightly but this particular feature can vary depending on where the wheel comes from. Continental wheels of this type can often have an extreme slope.

A castle wheel where the spinning assembly is below the drive wheel. This one is from Ireland.

Despite the fact that spinning had been a necessary domestic task verging on drudgery, spinning wheels could still be found in many homes here in Scotland, as well as abroad, as a nostalgic memory. They were proudly regarded as part of a family’s history for, in many cases, they had belonged to mothers and grandmothers. Wheels are often purchased from sale rooms as an attractive conversation piece in a sitting room.

However there is another side to this story in that wheels were taken to other countries, due to the Highland Clearances and immigration, where they would be a vital necessity in a new life. Hence, there are many examples of Scottish wheels in Canada, America or anywhere the Scots moved to. Also, it was not unusual for a woman to be given a new wheel to take with her on her marriage which could be far from her parental home. This could be a reason for finding a non- locally made wheel in another area. In one case, an Irish woman who married a man in one of the Western Isles took her Irish ‘castle’ wheel to her new home on the island and the Museum is very fortunate to have such an example. Despite migration and the passing of the years, we are lucky that there are so many wheels with such strong links with the past.

For those who are interested in the development of the spinning wheel in Scotland the collection in the National Museums of Scotland illustrates not only a period of increasing national prosperity in the 18th and early 19th centuries but also evidence of rural Scottish domestic life in a time before the advent of industrial production.

Most of the collection is in store but is normally available for visitors to study by appointment.

Any additional information on the subject which can be added to our archives will be most welcome. For instance, while there is a list of makers which has been added to over the years, there is little or no information about most of the men who made the wheels in the collection, such as dates of production and locations.

References:

Mitchell, Arthur; The Past in the Present, (1880)

Durie, Alistair J: The Scottish Linen Industry in the 18th Century, (Edinburgh 1979) John Donald Publishers

Dean, Irene F M; Scottish Spinning Schools, (1930) University of London Press Ltd

Scottish Life Archive, Research Library, National Museums of Scotland