In 795 AD one of the first recorded Viking raids in Britain took place at the monastery of Iona in what is now Scotland. Dozens of raids and battles would follow, leading to the plunder of people, cattle, and, of course, portable wealth by Vikings.

These events appear in the historical sources, but is there any archaeological evidence for these raids? Can we identify what was taken, and how much?

The answers to these questions are surprisingly hard to find. But unsurprisingly, the evidence in the National Collection might add some twists to the story. Here are a few examples of the material we have and how we can understand it.

Archaeology of a raid

The historical evidence for Viking raids in Scotland is valuable but patchy. From the Irish annals, yearly records kept at monasteries, we get glimpses of audacious raids on churches and fortresses. Even these are not the full story, because these chronicles only reported a few key events in each year, mainly those relating to churches and their royal patrons. In this sense, it is no surprise that we hear a lot about raids on the monasteries of Iona and Dunkeld, because they are where annals were kept.

The silences are perhaps more surprising – for instance, what must have been a catastrophic raid also occurred at Dunkeld in 878, because the Irish annals record the relics of Columba arriving in Ireland to ‘escape the foreigners’. Yet there is no record of any specific attack in Scotland that year. The annals cannot be expected to be a complete account of Viking attacks in Scotland.

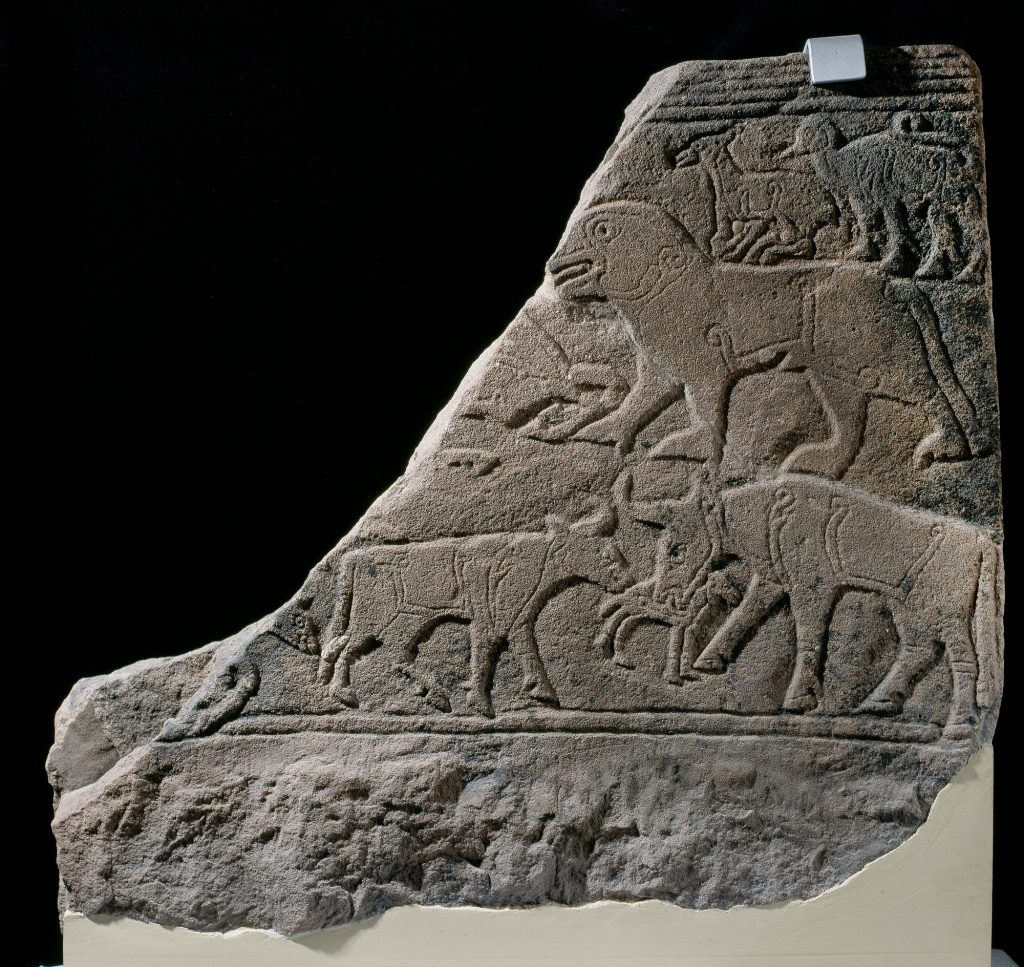

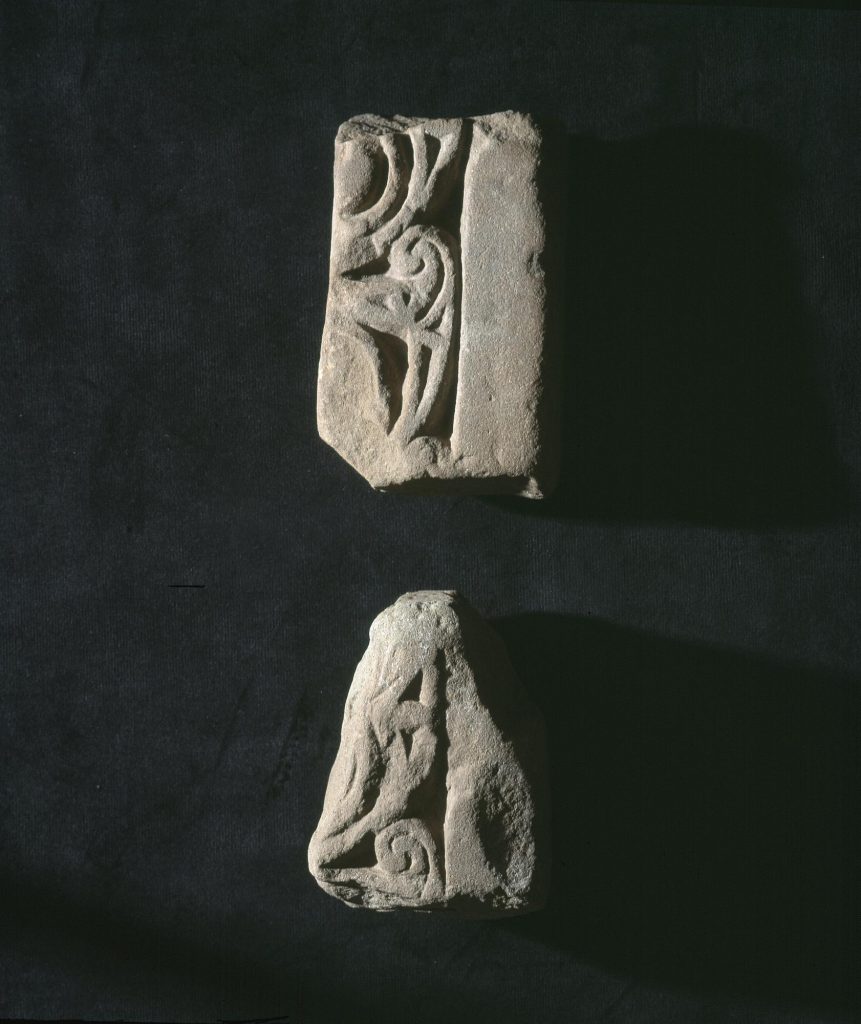

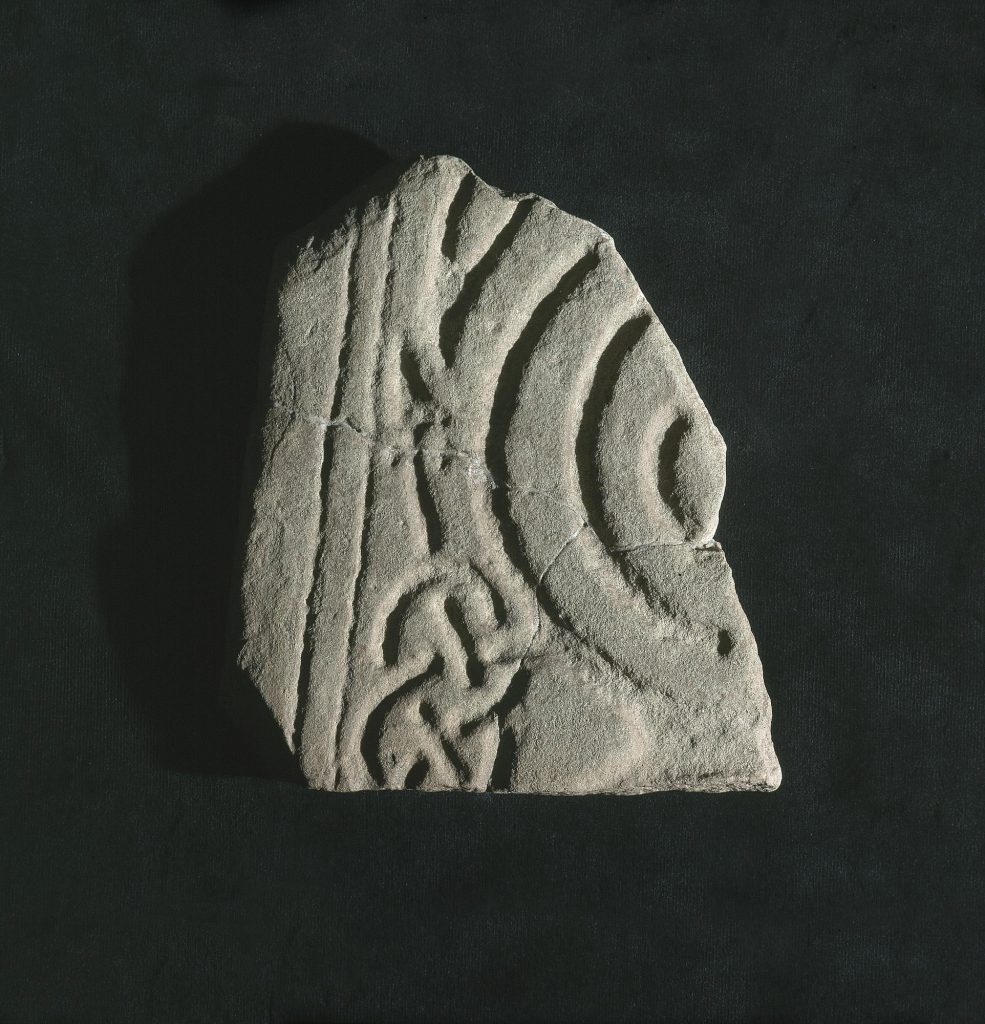

For all the attacks on monasteries we know did occur, finding archaeological evidence for them has been very tricky. The events of a single day can rarely be spotted in an excavation where centuries are compressed into layers of soil only inches thick. Out of all the early monasteries excavated in Scotland, only two have evidence for destruction events in the ninth to tenth centuries. At Portmahomack, the entire workshop area was seemingly burnt down, with smashed fragments of relief-carved crosses scattered throughout the ashes. Two individuals buried in the church have evidence for blade wounds to the cranium, and all of this is dated to within range of the ninth century. At Whithorn, the timber minster church and the adjacent stone chapel both suffered a catastrophic fire in the mid-ninth century. In both cases, these events seem to mark a turning point in the life of these two Christian sites.

These facts alone do not prove a Viking attack of course – Christians could and did attack the churches of their rivals even before and during the Viking Age, and accidental fires in timber-built structures can be catastrophic at any time. The case is rather stronger at Portmahomack than anywhere else when all the archaeological evidence is put together; the excavation report is available to download in open access via the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland – read it and judge for yourself.

Loot in burials

In previous posts I have discussed some well-known objects which were clearly looted by Viking raiders. We know this because in many cases they consist of metalwork elements and fittings from Christian shrines, reliquaries, altar plate and other ecclesiastical accoutrements which have been taken out of their normal functions and repurposed for use as grave goods. These include vessels and ladles which were likely used for holy water or wine at Eigg, Colonsay and Islay, or the hinged strap holders of a portable reliquary-shrine, which were refashioned into shoulder brooches and buried in a female grave on Oronsay.

In some cases, like the bucket mounts, the objects seem to have been ripped up and modified into dress fittings and mounts. In other cases, as at Oronsay, the objects were more carefully dismantled before reuse. One class of object which appears repeatedly in Scandinavian graves are ornate circular discs of silver, bronze and gold, sometimes repurposed as disc-brooches. Circular and bossed mounts can be found across the diverse category of Christian decorated objects but many of them seem most likely to derive from book-shrines. One of my personal favourites is easy to miss in our galleries, a raised gilt bronze disc 7cm across with a raised setting for what must have been a sizable jewel or amber inset now lost. This object was not seemingly used as a brooch – the woman in the grave was already wearing a penannular brooch, an insular buckle, and traditional Scandinavian oval brooches – and must have been used to decorate another object now lost, perhaps a box or bag. The three-dimensional nature of this object means it may have come from an impressive shrine, or more likely the central fitting for a cross, whether in stone, wood or metal.

Above 3D model: Insular mount with central blue glass setting found in a Jåttå – Stavanger, Rogaland (Arkaeologisk Museum – University of Stavanger S14171; shared from Sketchfab.com, CC BY 4.0

Interestingly, such objects tend to be found in female graves. The traditional explanation is that male raiders brought back prestigious trinkets from far-off lands as a form of bride-wealth, worn by the woman as a reflection of the status of the man. However, such interpretations hold less water when they appear in Scotland itself, where the loot may not have come from very far at all. It is possible that here the message was partly directed at the local population, who would have recognised the kinds of objects they represented. As tokens or recognisable parts of what they once were, it is also possible that an aspect of their sacred power as former reliquaries was being adopted in a polytheistic context. Less well explored is the likelihood that some of this material was not looted at all, but rather was exchanged as tribute, or even as part of marriage alliances. This might explain why some objects, like the Westness Brooch, survived intact. As the St Ninian’s Isle Hoard demonstrates, the wealth of the Church was derived from the kin-group of its secular patrons, and this hoard contained objects from both secular and ecclesiastical contexts. We know from scientific testing that many of the women in Viking graves from Scotland were not Scandinavian, and so we cannot exclude that some of the Insular objects in their graves came with them.

Viking panic!

Several hoards of precious metalwork and other goods have long been proposed as evidence of what you might call ‘Viking panic’. Most famously, the above-mentioned St Ninian’s Isle Hoard stashed in a chapel c. 800 AD has been considered a Pictish ‘security deposit’ that was never retrieved, in an area of considerable Scandinavian settlement. There are several hoards across Scotland which are dated to the ninth century which may be the product of increased anxiety over portable wealth in an age of raids, but the problem is that most of these are dated by the art style of their objects, and deemed ‘Pictish’ or ‘native’ hoards only because they do not contain Scandinavian material.

However, some hoards have a combination of objects from home and away which must relate in some way to ’Viking’ activity – the raiding, trading and travelling that typify the perception of the Viking Age. For instance, the Talnotrie Hoard from Galloway is dated by coin to the late ninth century, perhaps around AD 875, well into the age of raids and into the era of settlement. It contains complete Northumbrian and Mercian silver dress items and coins, plus other odds and ends including gold offcuts and spindle whorls which has led to its interpretation as a stash of a travelling craftsperson.

The lead weight is itself evidence of looting, as the decorated gilt bronze object has been cut from an existing insular object and refashioned into a different kind of object. Until recently it was one of very few from southwest Scotland, including some from the Viking-age trading outpost at Whithorn. But two more have recently been found in neighbouring Dumfriesshire and acquired by Dumfries Museum through the Treasure Trove process, all similarly topped with fragmented Insular gilt objects. They show that southern Scotland was more involved with Viking-age trade than was first appreciated, and potentially able to trade with both the Irish Sea zone (via Whithorn) and the Danelaw zone (as indicated by the objects with Great Army connections).

It is still not clear who owned the Talnotrie Hoard and why this was secreted at the cusp of the period of Scandinavian settlement. A recent reassessment of artefacts relating to the ‘Great Heathen Army’, the group of Danish-led warbands which harried England from 865-878, argues that this hoard fits perfectly with their archaeological ‘footprint’: the juxtaposition of exotic coins of Carolingian king Louis the Pious and an Abbasid dirham from the Baghdad caliphate, along with a decorated lead weight typical of market sites and Viking encampments. And there is even a plausible historical connection to the Viking Great Army here – in 874/875, Healfdane’s warband was said to have gone raiding in Pictland and Strathclyde, fitting in with the proposed date of deposition of Talnotrie (the latest dated coin is dated 852-74).

The proposal that members of the Great Army might have lived or settled in Galloway or at least travelled through it, might support an identification of the Talnotrie hoard as what is traditionally thought of as a ‘Viking’ hoard. But perhaps it is safer to say that the hoard is a reflection of its time, a chaotic period of indiscriminate military plundering, rather than assigning it a ‘Viking’ origin.

Finding the Insular Vikings

These examples are just a glimpse into the kinds of objects we know to have been the product of raiding activity. What is interesting to me is just how much of the material from graves and hoards in Scotland is of Insular rather than Scandinavian origin. The fascinating mix of Insular and Scandinavian dress accessories in Viking graves will be the subject of future posts.

But as we have seen with recent work on the Galloway Hoard and the Scotland’s Early Silver project, the hoards of the period can no longer be seen so neatly as a ‘foreign’ practice. There are signs of an emerging market economy across Britain and Ireland which was not invented by the Vikings, but accelerated by them during the ninth century. Nor can we read the ethnicity of the person (or persons) depositing hoards, given they are composed of movable wealth. With new research led by this Museum, it is clear we now need to revisit a lot of our assumptions about even famous hoards and burials on display in our galleries.