National Museums Scotland opened a permanent Fashion & Style Gallery in 2016. The opening case, ‘Designing and Making Textiles’ focuses on innovation and manufacturing developments within the textile industry and how the industrial revolution both created and fed a desire for the new. Included is a display on how advances in the use of colour led to 19th century dyers expanding a burgeoning fashion trade.

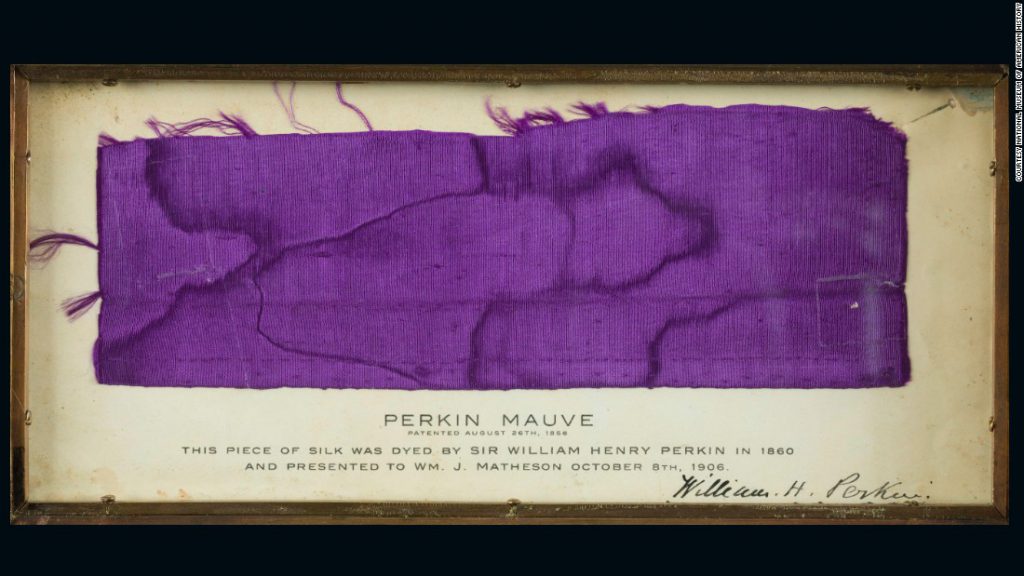

Senior Fashion Curator, Georgina Ripley, had selected a purple bodice from a 3-piece outfit, c.1870, to help tell the story of the first synthetic aniline dyes. Aniline dyes are now well known for their toxicity and poor resistance to light, but in the 1860s they began to be mass marketed to wide spread enthusiasm following the launch of the first patented synthetic dye, known as Perkin’s Mauve (discovered in 1856 by the chemist William Perkin) or mauveine. Historically, the colour purple had been particularly rare and costly to produce from nature and mauveine became a sensation, sparking a great fad for clothes and furnishings in aniline purples. A host of other novel shades appeared including fuchsine, methyl violet and Scheele’s green.

Despite their popularity, the dyes were found to be fugitive, susceptible to fading, and with a toxicity that posed a danger to health in production and wear; elements of Victorian society also roundly criticised them for being too ‘gaudy’. They sometimes contained other toxic ingredients – arsenic in your clothing anybody? Following a boom period, a complex variety of economic factors together with safety concerns and poor durability halted the rise and rise of aniline dyes. Most challenging for Museums’ today is how to safely display these objects. They are known to fade dramatically with light exposure even at Museum levels (normally 50-100 lux for organic materials) and so including the aniline dyed bodice in a permanent gallery was almost a contradiction in terms, since it would need to be taken off display after only a few months.

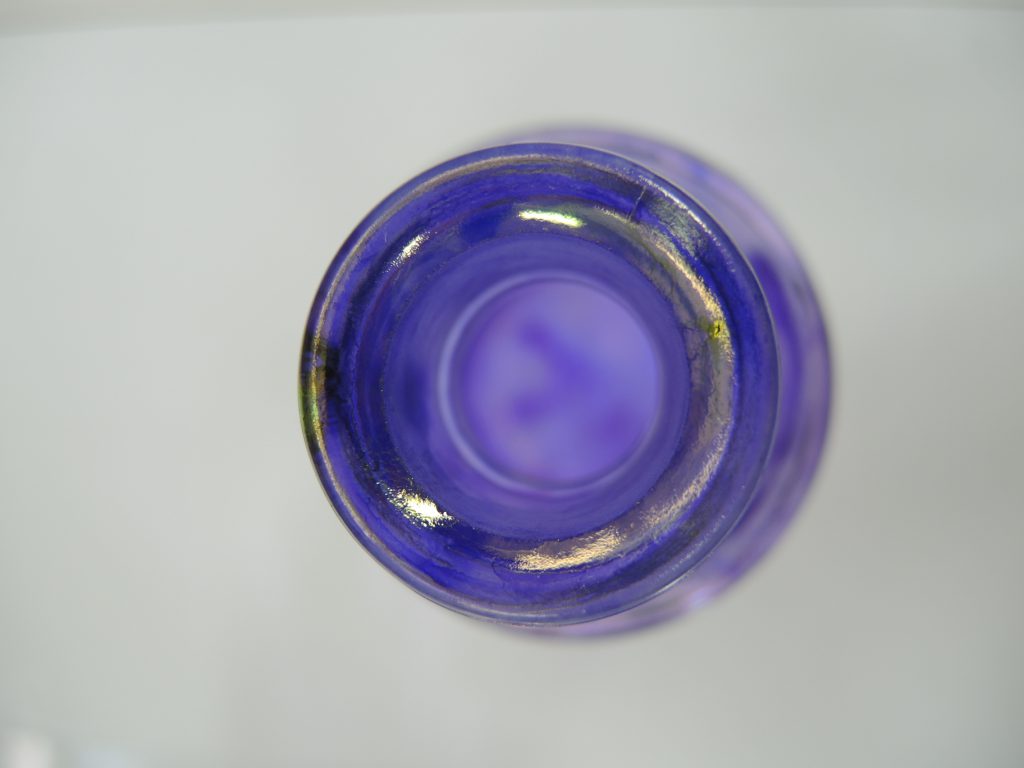

The way the silk bodice had faded was not immediately apparent; the colour looked rich and deep with no obvious signs of fading. I searched in the concealed areas for visual evidence – and found it (above); interestingly the colour had not so much faded overall as lost its intensity in the blue spectrum, changing from a blueish purple, to a pinker purple.

To help make a recommendation about how long the bodice could be on display, I took it to National Galleries Scotland where a collaborative project was underway. Senior Conservation Scientist Bruce Ford, an expert in micro-fading at National Museum of Australia, was visiting Edinburgh to assist and develop expertise in the field of micro-fading with Kirsten Dunne of NGS. Micro-fading is a tool which helps risk assess the length of time an object can be on display before visible fading occurs. The test uses fibre optics to reflect a tiny area of light (approximately 0.3mm – 0.40mm) onto a discreet area of an object. The area is simultaneously monitored using software to calculate the spectral change in real time using industry standard CIE colour difference equations. Typically, new dyes will fade at their fastest rate for a short period, plateau and then slow down. However the bodice test showed the aniline dye kept fading rapidly with no plateau and no decrease, confirming it would only be possible to show the bodice for six months with very low lighting, followed by 10 years ‘rest’ in storage.

Mauveine is frequently mentioned in the history of aniline dyes, but there were many other aniline purples of the period. With this in mind, I thought we should make clear what ‘our’ bodice was actually dyed with. I requested dye analysis of the bodice and other aniline purple costume in the NMS collection from Analytical Scientist, Lore Troalen. Lore carried out the analysis using our in-house Liquid Chromatography system, which allows the separation and identification of each single component used to form the colour.

The analysis showed that the bodice is dyed with a complex mixture of nine different dye components. Lore identified three separate methyl violet dyes (mainly methyl violet 10B), three fuchsine, and traces of three benzyl violets. Although it is possible that the violet dyestuffs were intentionally blended to achieve the final colour, Lore felt it more probable that impure starting materials generated this mixture of different dye compounds. Methyl violet is very sensitive to light and will quickly fade, but benzyl violet and fuchsine dyes are less susceptible. The dyes different reaction to light explains why the blue hue (arising from the methyl violet) of the original bodice is noticeably reduced but the overall colour can still be read as purple, if in a different, pinker shade.

There did not seem to be an easy solution, but as the analysis proceeded I proposed that the bodice could be replaced with a replica after six months display. I also had the notion that it might be interesting to compare how different types of dye fade by making one side of the bodice with purple aniline dyed silk, and the other side dyed to match with modern reactive dyes, a sort of real-time experiment in fading. The display would then have a special interactive added to inform viewers that what they were looking at was no longer original, and why.

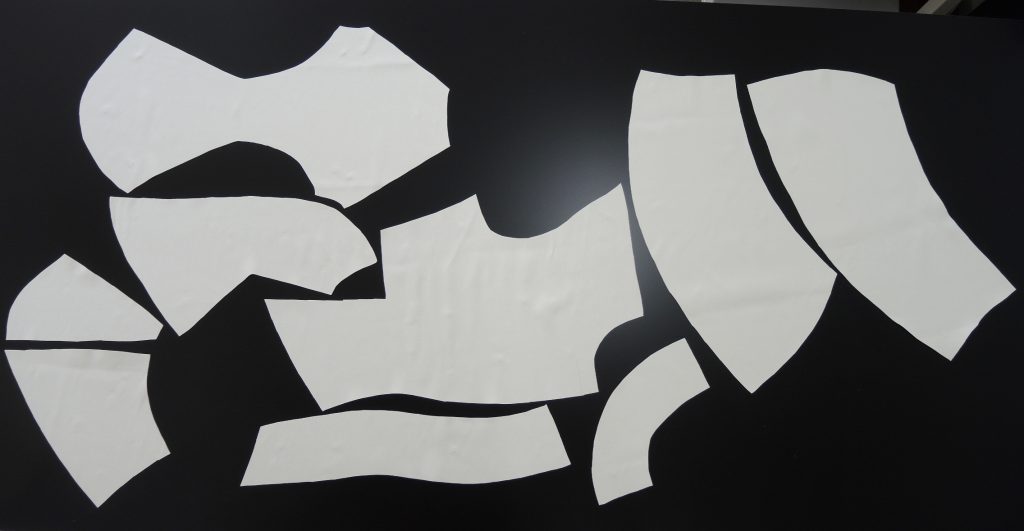

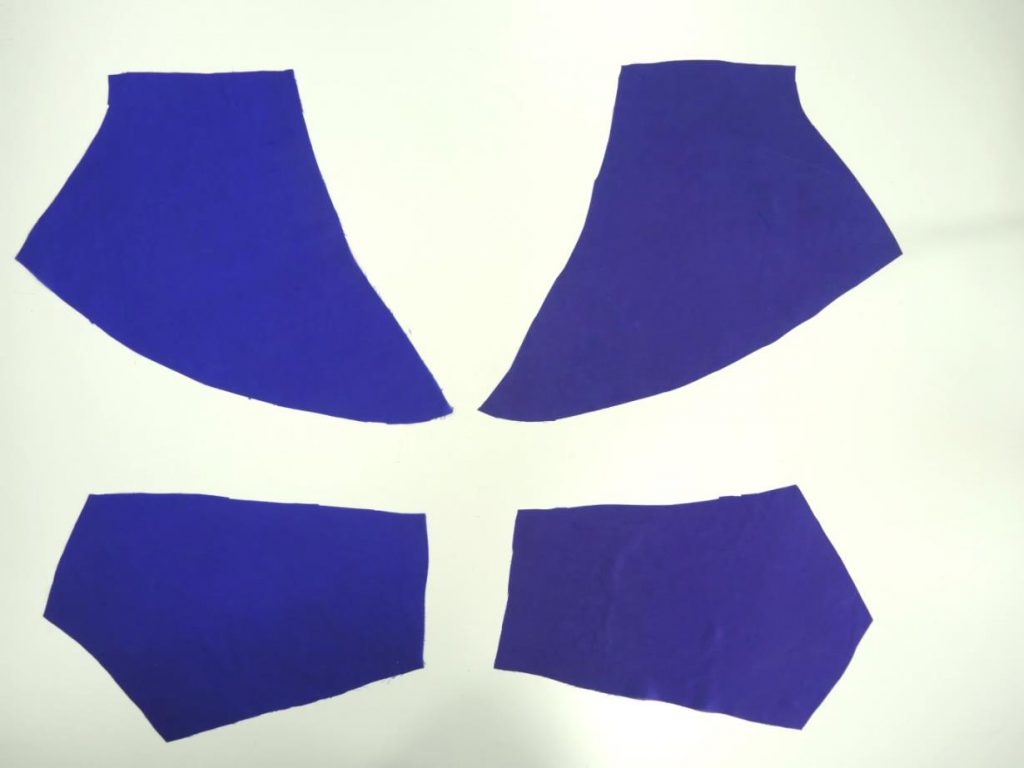

My first task though, was to take a pattern of the bodice. Patterns can be drafted using lens tissue and a soft pencil, such as a 5B. It is necessary to pad out any areas of fullness, like the sleeve (above) in order to capture the full dimensions. Measurements can be taken from the object for comparison with the tissue pattern that is produced, and refinements made of the draft until a full pattern is achieved.

I also took lots of detail shots of the bodice to help me make the replica, which I would do after the gallery had opened. I found there were lots of discrepancies in the cut and construction which you would not expect to find in costly clothing today. For instance, the wide trim varied very considerably in width, by as much as 2cm in places. The pattern pieces were also not fully identical on the left and right sides, which suggests they were cut for maximum economy in a single layer rather than the double layer dressmakers normally use today.

Detail of the trim embellishment on the front and at the side bodice

Once the pattern was drafted, I made a copy of the bodice in calico, also known as a toile. Only one side of the garment is made up, unless it is a non-symmetrical style. The toile was fitted against the bodice mount, which was a bespoke mannequin made in clear acrylic. The original bodice would soon be on display in the gallery, so it was important that the toile fitted well to ensure the replica would also be the right size.

The toile being made and fitted

The replica fit was good, and corresponded well with the original bodice. The bodice is fitted at the waist, but with fullness across the shoulder blades and long almost banana shaped sleeves. The fullness in the back looks quite strange unpadded, but in wear would have been softly rounded out by the underclothing, likely to have comprised of a corset and a chemisette or blouse.

Meantime, the bodice itself required a little conservation before going on display, which consisted of surface-cleaning and a small amount of stitched support where the silk had worn thin under tension. The acrylic mannequin then had ‘soft’ arms attached and silk pads were made to slip inside the areas of fullness, helping to bring out the bodice profile.

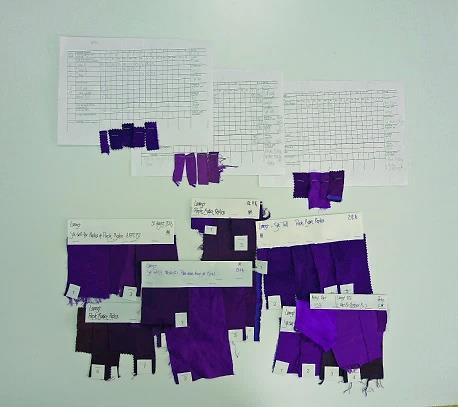

I then embarked on dyeing cloth for the replica, and it’s fair to say I was in a purple haze for quite a while. NMS Analytical Scientist, Lore Troalen, was my touchstone for using the aniline dye, which she also sourced for me. Happily, this was also a methyl violet (the composition was not identical to that of the bodice), and I was going to use it without other aniline dyes.

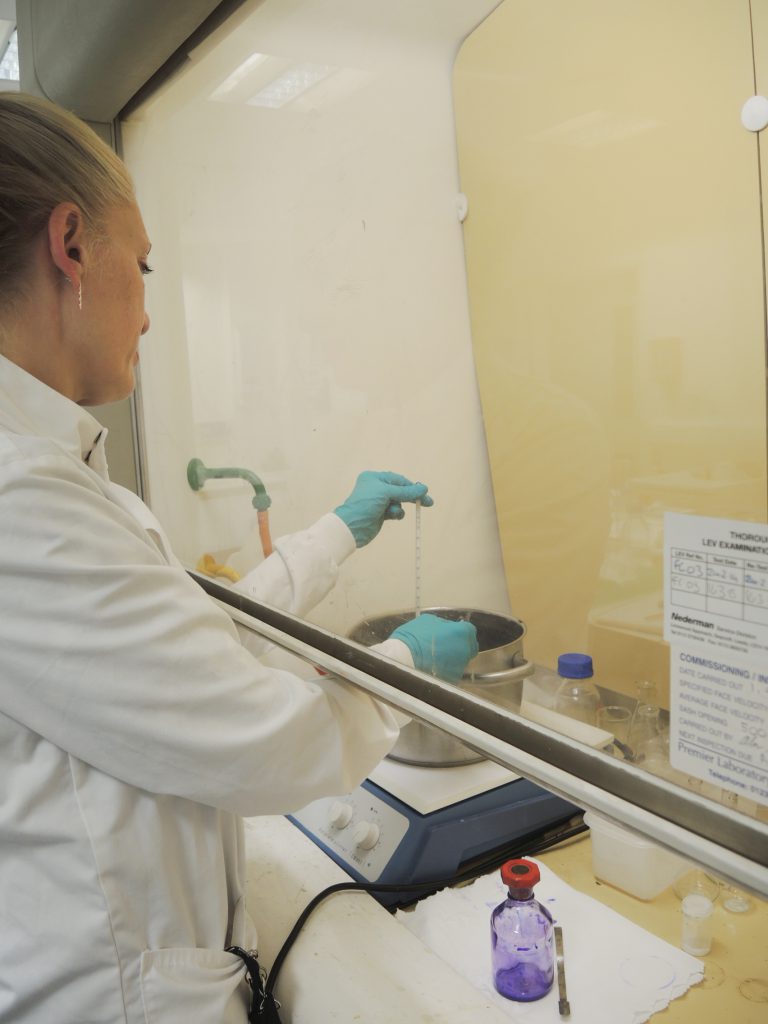

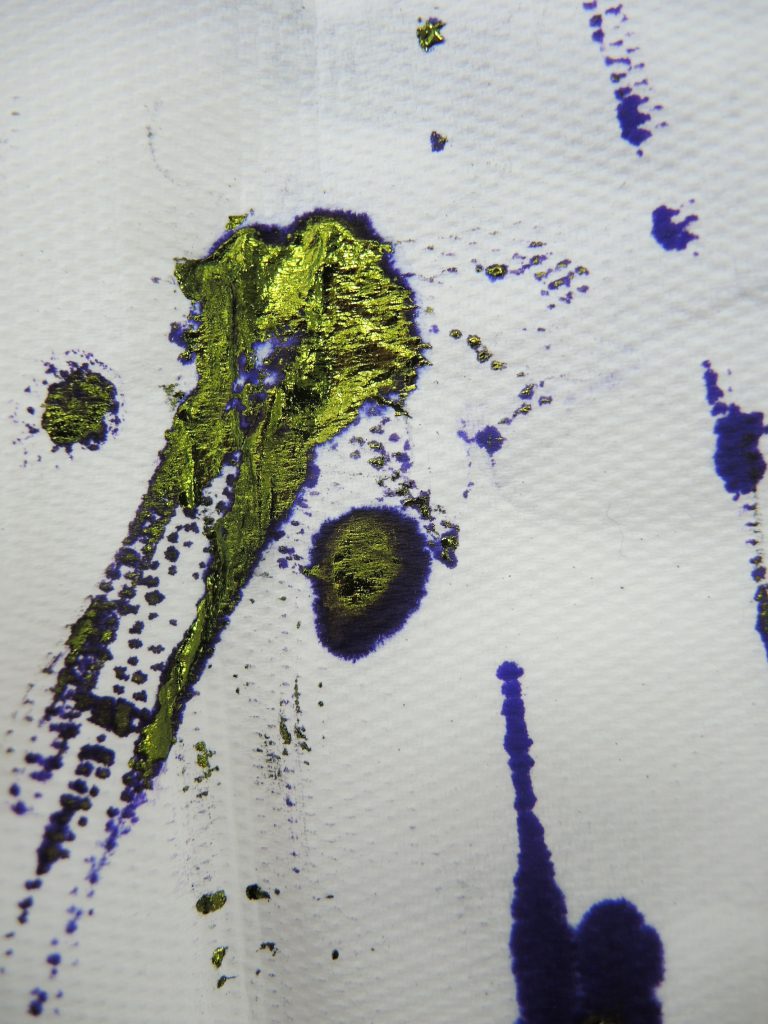

Dyeing silk with methyl violet in the fume hood: tarry residues from the methyl violet solution

Lore had advised me that the dye powder was incredibly prone to drifting, which was indeed the case. I took care to use gloves, goggles, lab coat, and especially face mask, as I also found the particles very mobile. For safety reasons, the dyeing took place inside a fume hood. I found that in solution the dye formed an unpleasant tarry residue which I assumed was due to the coal tar the aniline derives from. In the centre and on the right are the dye bottle and a paper towel I used to wipe off a glass stirring rod. I found the appearance of the deposit quite disturbing! Dealing with the dye in only a very small quantity convinced me that it could only have been a dangerous substance to have to work with daily.

The main challenge of the dyeing process was colour matching the aniline dye to the modern reactive dye. I found that the depth of shade was the hardest element to match. The aniline dye had struck the silk fibres immediately and with some intensity, which made sense of the historical accounts describing the vibrancy of aniline colours. However, with reactive dyes the cloth normally uptakes colour throughout the dye cycle, culminating with the greatest uptake when the dye bath reaches higher temperatures. In the end I achieved a good colour match, but you can see a small difference in the concentration of colour.

A group of visitors see the replica during construction, and a detail of the inside of the curved sleeve

The construction of the bodice was more straightforward. Although I had made a faithful copy of the pattern pieces, I used modern techniques for the sewing. The bodice was largely machine sewn with hand sewing completing elements such as the trim and pleated cuffs. I did adapt from the Victorian method of bodice lining, which I found to have marked differences in construction on the left and right sides. It seemed that in terms of method, consistency mattered less to the Victorian dressmaker than it would do today.

The replica being fitted and installed in the Fashion & Style Gallery in early 2017

Six months after the Fashion & Style gallery opened, I took the original bodice off display and fitted the replica onto the mount. Our Audio/Visual technicians fitted a new interactive in front of the case, and the replica is still on display there today. Unlike the original bodice, the replica can stay for as long as it’s required without concern for how much or fast or differently it fades! Like the original though, I suspect the change will be relatively subtle. After 3 and a half years in Museum conditions, and even lit at a very modest 30 lux, there probably has been a visual change, not yet immediately apparent but still there. Have a closer look if you get the chance.