Working at home, away from the Museum building, has encouraged me to think about the importance of ‘place’ for great museums like ours. Looking out of my study in South Edinburgh to the glow of gorse on Arthur’s Seat brings into focus the very particular location we inhabit.

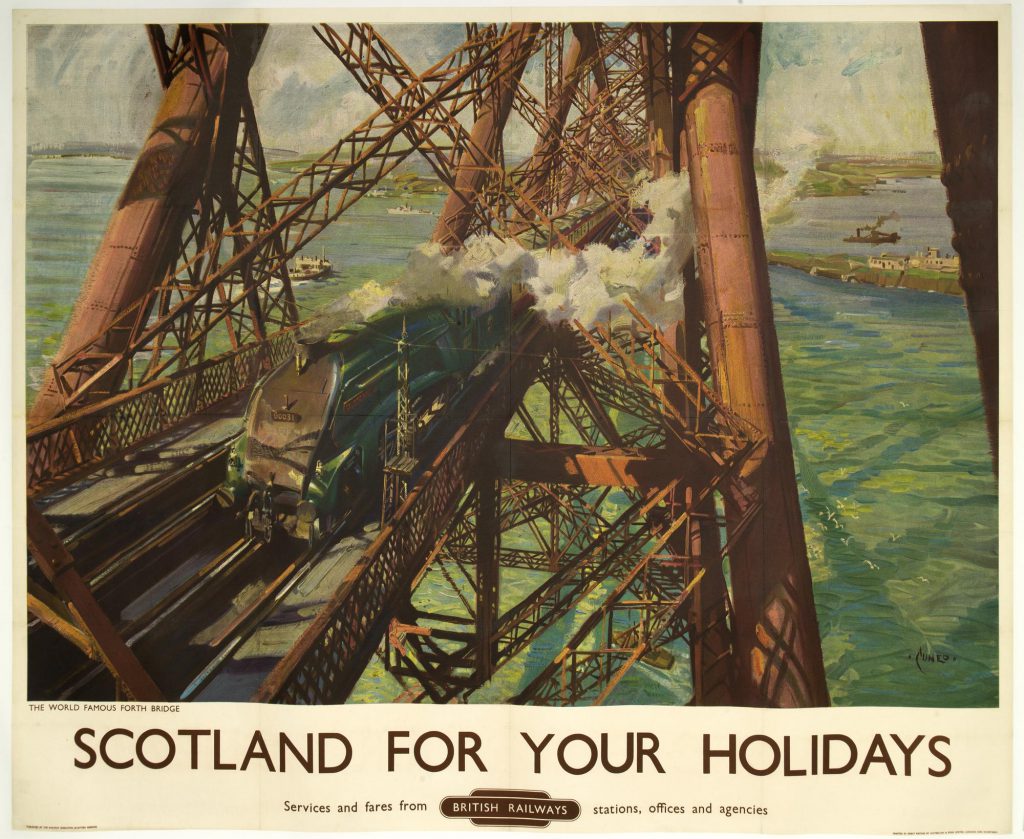

Of course, Edinburgh’s geography and architecture lend themselves to reflections on the shape of the landscape beyond. Those glimpses from the window of a train or plane as it pulls into the city sharpen its dramatic topography, its proximity to open water and steep hills. It’s a sensation visitors may share when they look out over the Old Town or across to the Pentlands from our roof terraces in Chambers Street.

That exhilarating feeling on encountering the ‘Edinburgh sublime’ is something that has stayed with me since I relocated to Scotland to live and work in 2011. Reflecting back, there was nothing before that really prepared me for it. Born in Bristol and resident until then in London, most of my family history resides in England (with maternal ancestors arriving from Cork in the nineteenth century). Bristol, Somerset and London were very different places.

Scotland featured as the location for one family holiday in Fife in the early 1980s, my father retracing schoolboy memories in St Andrews (he attended Madras College when my grandfather was stationed at RAF Leuchars in the post-war years). But on the whole my sense of Scotland through a 1970s childhood had been informed by Robert Louis Stevenson novels and a treasured recording of Isobel Baillie singing the ‘Skye Boat Song’. My favourite toy was a wooden marionette, loosely based on Harry Lauder, and white pudding was an exotic and rare addition in Somerset fish and chip shops. It was a place of the imagination, strongly infused with romanticism.

Thirty years on I felt I knew the terrain a little better, at least from a ‘curatorial’ perspective. The National Museum and the wider world of contemporary Scottish material and visual culture seemed somehow more familiar. Glasgow’s status as City of Culture in 1990 had redrawn the map if you worked in the arts or heritage. Several of my close colleagues at the Victoria & Albert Museum in South Kensington had started their careers in Scotland’s museum and gallery sector in the 1980s and 90s (and they were always the ones with the good ideas). Indeed, my first night in Edinburgh, following confirmation that I would be coming to take up the role of Principal of Edinburgh College of Art, was spent with those same workmates, in the spectacularly re-furbished Grand Gallery, as guests at the gala for its re-opening. What an introduction to Scotland’s past, present and future!

Which brings me back to National Museums Scotland now and the view over to Arthur’s Seat. When we get back into the National Museum of Scotland building one of the first things I will do is climb up through the Scottish Galleries to the roof again, taking in the links between our objects and the story of the wider nation. Once I’m at the top, I’ll look out towards the Crags and across the Forth and reflect anew on the Museum’s role as microcosm and palimpsest of all that makes Scotland unique and connected, and I’ll think about how best we might share that with you, our partners, followers and visitors in the months to come. Home is about more than the imagination. It’s about things, people, spaces, stories, emotions and ideas. Museums help to bring that sense of home – and the imagination alive.