In 2019 National Museums Scotland opened a new Egyptian gallery. Many objects chosen for the gallery had either never been displayed before or had not been shown for a long time. Of these were some exciting textile items which connect us personally with the people who used or wore them, giving a sense of lives lived long ago. In textile conservation several fabulous objects arrived for us to work on, including a painted shroud, a mummified girl, and a humble single sock.

The Museum register records that the sock was probably found in Akhmim (Ipu in ancient Egypt), and dates from the 4th – 5th century AD, making it at least 1,500 years old. It was most likely to have been excavated from a burial site, and was acquired by the Museum in 1911 from the Egyptian collection of Frederick George Hilton Price (1842 – 1909), a banker and collector.

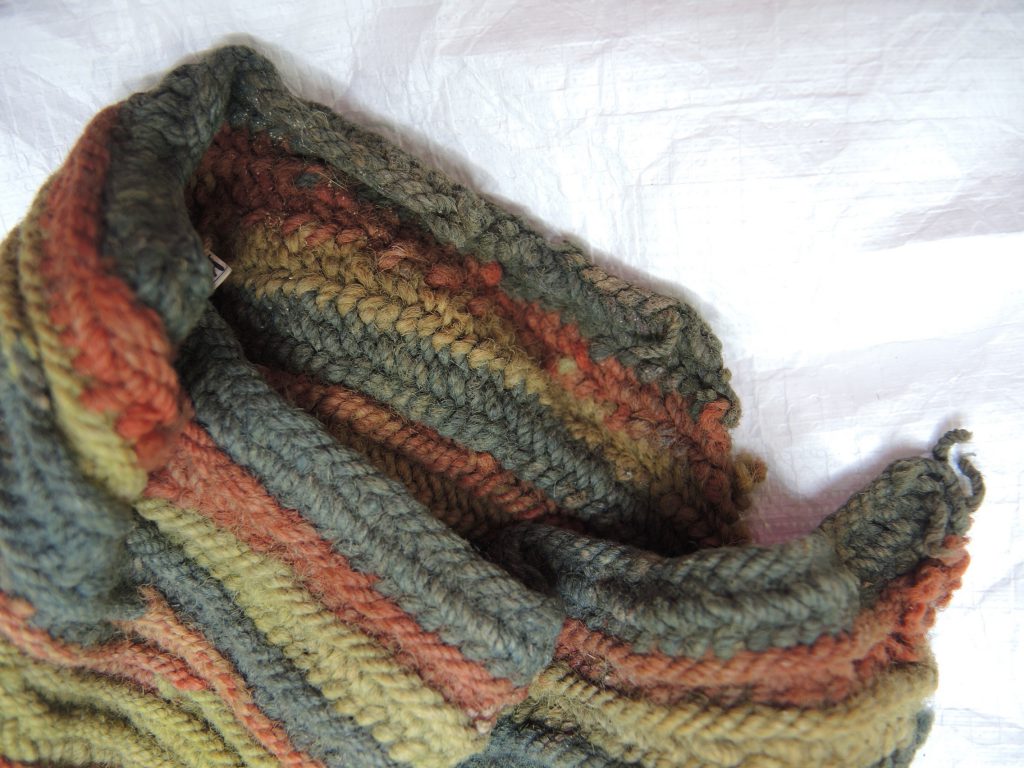

The sock is composed of 4 different coloured wools in non-continuous stripes of colour. The construction method involves a knot and loop technique which produces an attractive, well balanced, flexible ribbed cloth with distinct twill type patterning between the ribs. The cloth was certainly fit for purpose; the rib would have allowed the material to stretch and be able to move comfortably over the complex shape of a foot with ease. Indeed, the sock retains a surprising extent of flexibility given its vast age – in sock years – and condition. The caveat for the conservator is that this quality cannot be exploited during treatment. Whilst the sock is largely complete, the dryness of the fibres and around 11 holes prohibit significant handling of any kind.

However, the most notable feature of the Egyptian sock is the divided toe. In wear, the intention may have been to house the big toe in one ‘sock toe’ and the 4 smaller toes in the other. Although this sounds rather cramped, socks of this type may have been designed to be worn with thonged sandals, and in that case, such a division would have been necessary. Perhaps the notion that you would require such a sock in a hot and arid climate seems a little strange, but cooler evenings and a change to damper winter weather would have made the wearing of socks and/or sandals desirable for wealthier members of Egyptian society.

Example of Nålebinding…

…compared with Egyptian sock toe

The toes were probably the place where the sock was begun. The technique, called Nålebinding, is often mistaken for knitting but is in fact a single needle technique more akin to sewing; it requires finite lengths of yarn which are threaded through a small loop and then knotted in the process of completing a stitch and starting a new one. In beginning, the stitches could be worked with a long, broad needle to the round shape needed by pulling up a line of stitches tightly. When the yarn becomes too short to work new stitches, a new length is tied on to continue the work and any loose ends cut off to neaten. By deduction, it seems possible that these shortish lengths of different coloured wools may have otherwise been waste products, usefully put to purpose. Care has been taken to ‘tip’ the ankle with blue yarns, but some ribs stop and change colour mid-way, also suggesting economy of use.

The conservation work on the sock began with standard examination and photography, but with a real focus on ‘getting to know’ the object. During this time various strategies can safely be proposed, thought through and revised, whilst further information and familiarity is gained with the object. Some of the condition notes I recorded are below:

Assessment; The overall condition of the sock is poor. It is dry and the fibres friable. The sock is squashed very flat and brittle folds have formed in places. There is heavy ingrained and particulate grey dirt soiling and stains throughout. Brown coloured soiling and stains are heaviest along the length of the inside sock; the soiling pattern is inconclusive though could be related to burial. Some white particulate soiling scattered throughout, perhaps moth residue and / or salts. There are compacted brown grey accretions around / on the front proper left (?) toe which appear mineralised under magnification. A metal pin (with head removed?) is completely embedded through one toe and has green copper coloured corrosion around it on the front and reverse sock; it is unclear whether the pin relates to previous display. There are various holes, some / all related to moth damage. All the holes are fraying and vulnerable to further damage. The holes are causing considerable structural instability to the overall form and the object must be handled with great care to prevent further damage and loss.

The sock was indeed squashed flat, and moreover in a vulnerable state owing to a combination of degraded and embrittled fibres and structural instability, caused by holes, tears and soiling, a combination of types which will gradually disrupt fibres and textile structures. In this tender state the sock was also quite distorted – and therefore the personal association was diminished. The sock’s pancake-like condition was not helpful for applying necessary support either. Its stability could be improved with well-integrated fabric support patches, but these could not easily be employed unless the sock was in a better 3-dimensional form.

Micrographs of green and red fibres

Further examination of the fibres was carried out with a digital microscope. The most distinctive outermost feature of new wool fibres are overlapping scales which form a sheath around the internal structure. New scales are very porous, but as wear, washing and age proceed will wear quite smooth, so the aged scales are barely visible now. It was possible to observe many microscopic particles of mineralised salts and copper corrosion, which related to a nail or pin driven through the toe, presumably when used as a display method at a long previous time (disclaimer – we don’t do that now!).

After thorough examination and discussion with our curators, the decision was taken to humidify the sock in order to reinstate it to a more ‘sock’ like shape, as it was felt this would be the best way to provide it with some lasting stability. To introduce humidity to something as old and fragile as the sock, it is vital to introduce moisture at a consistent but slow pace to help the aged fibres gradually acclimatise. If not done carefully, it is possible to ‘shock’ the fibres, which in the worst scenario will cause further splits and fibres dropping out. So it was with some trepidation that I embarked on the sensitive humidification process, using a chamber with a clear plastic cover and a hygrometer to measure the changing levels. To raise the humidity, I used muslin strips dampened with filtered water, adding more gradually, until over 2 hours later the level was raised to 70% relative humidity, which I felt was as high as the sock should be taken given its’ vulnerability.

At this point I used the ankle opening to insert loosely bundled silk into the sock; it was a good thing that there was no turning back at this point, as it was quite nerve racking. However with very careful handling and some persistence, I managed to gently bring out the profile – one area was so brittle (possibly due to fluid seepage of some kind) that I did not attempt to bring out a long, rigid fold, which causes the sock to lilt to one side.

The first type of support the sock needed was an internal mount. I made a two piece mount made from a thermoplastic polyfelt called Fosshape™ padded out with polyester wadding. The two pieces aid placement of the mount into the sock without the need to flex it unduly at the ankle as it is positioned inside. The mounts were then covered with silk habotai colour matched with the green of the sock.

The sock mount during and after completion

The toe patch cut and gathered up to shape

The second stage of support was to place fabric support patches underneath the holes. I chose to use a custom-dyed brown silk crepeline, which is semi-transparent. I felt this quality could help improve understanding of the object; one of the sock holes reveals the outer toe(s) and I wanted to help retain the sense of a foot beneath the garment, as well as provide a lighter less visually disruptive means of support than a heavier cloth, as the weight and surface characteristics of the Nålebinding would be very hard to match well. Above is an image of the toe patch, which was cut and shaped with long stitches pulled up at the toe to follow the line of the sock. All the patches were stitched into place using various conservation stitches with silk thread.

Before…

…and after toe support

Everything went as planned with the support patches – the silk crepeline was as tricky to work with as expected! It is prone to bruising, stretching and moves round an awful lot while you are working with it. However, the key thing was the material felt right for the object – a nice light addition which nevertheless provided an appropriate level of structural support to stabilise the sock. I chose to stabilise the top edge of the sock with a flexible strip of clear conservation grade plastic, called Melinex®, rather than make the mount wider and ‘fill’ the shape completely, as is often done with internal supports. In so doing I hoped to visually imply that the sock was on a foot, whilst providing edge support with Melinex ®.

It’s the kind of object people are drawn to – perhaps a talking point for all to compare with our own sock drawers? Who knows…. But as some of you may have seen recently on the TV programme, ‘One Night in the Museum’ (BBC Scotland 1.4.2020) some younger visitors entered into a short but heated debate on whether it was ever ok to wear socks with sandals……. !