Over the past year I have been working with colleagues from National Museums Scotland and museums across the country to identify ancient Egyptian objects in Scottish collections. Though Scotland is a long way from Egypt, objects from excavations and collectors have made their way into 25 collections in Scotland, from the Scottish Borders to Orkney! The objects vary greatly, from tiny delicate amulets to monumental blocks of carved stone and everything in between, from papyrus shoes to musical instruments, and painted coffins to beautiful statues. I have had the privilege to learn about all of these collections, share my Egyptological knowledge with our partner museums and see the amazing impact this work has already had.

This is the first time that research like this has focussed entirely on Scottish Egyptology collections, but it is not the first time that people have wanted to survey museums. In 1887 the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland funded a report of all the local museums in Scotland; in that report Egypt was mentioned only 15 times, mostly to do with mummified human or animal remains. In 2005-6, a review looked at Egyptian collections in the UK more broadly, providing excellent ground from which to start this distinctly Scottish review.

Things have changed a lot since 1887 and we can now track around 14,000 ancient Egyptian objects in 25 Scottish institutions, spread across around 50 sites. This makes the review the largest survey of its kind ever completed for Scotland. It shares the greatest amount of information about the collections, their origins, donors and archaeological sites ever gathered. We identified and recorded nine collections which had not previously been recognised. These include collections right on our doorstep in the University of Edinburgh and head all the way up to Stromness Museum, making the faience shabtis there the most northerly Egyptian objects in the UK.

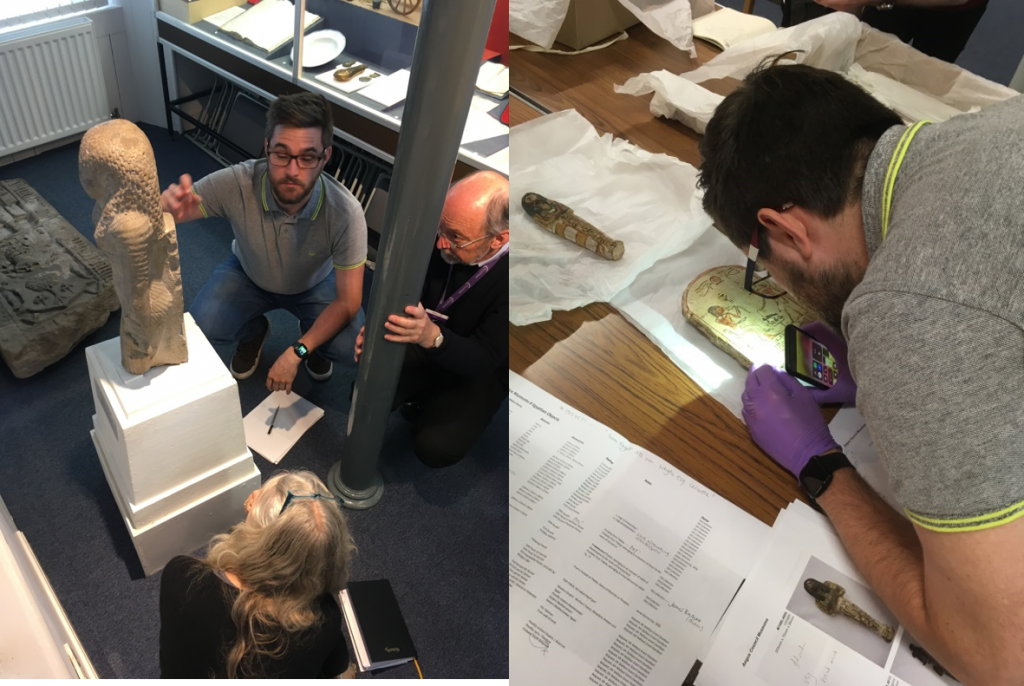

To gather all the details of 14,000 objects is no mean feat, so I have spent a lot of time working through the databases and catalogues of the museums and transforming lines of information into something everyone can understand. I have also had the good fortune to visit a handful of museums and look at all of their Egyptian objects. This sometimes had an Antiques Roadshow feel to it, where I could tell the museum staff more about the objects they had on display or in storage. Sometimes this would mean identifying objects which were made for the tourist market or explaining what an object was used for in antiquity, but my favourite thing to do was reading hieroglyphic inscriptions for the first time in decades, centuries or possibly millennia. There aren’t too many people who can read Egyptian hieroglyphs, so the information I could provide was really helpful for the museums, but it goes further than that: restoring the name of the owner of an object or a monument after such a long time feels very personal, connecting us more deeply to the ancient people who made these things.

With all this information I have been able to connect objects, sites and donors spread across the country, giving a clearer picture of Egyptological collecting in Scotland. There are hundreds of stories to tell, but for the meantime, here are three to whet your appetite and show the sort of research that has been done.

Meramuniotes and Dr Burnes

One of the most interesting objects I researched is a statue in Montrose Museum, which depicts a temple musician named Meramuniotes who lived around 300 BC. I have been able to reconstruct her family tree, and now have 18 family members which connect to Meramuniotes, one of whom even has a statue in Glasgow Museums. Meramuniotes’ statue was collected by Dr James Burnes of Montrose (1801–1862), a cousin of the immortal bard Robert Burns. James was a physician in India, who collected the statue on his way back to Scotland from his posting on sick leave. He was a fascinating person who was knighted by King William IV, dined with a young Princess Victoria and wrote a book that would inspire The Da Vinci Code. He can also be linked to another Scottish physician, Dr James Pringle Riach of Perth, who donated his Egyptian collection to Perth Museum & Art Gallery. I later found out that Riach and Burnes were friends!

Leaving a gift behind

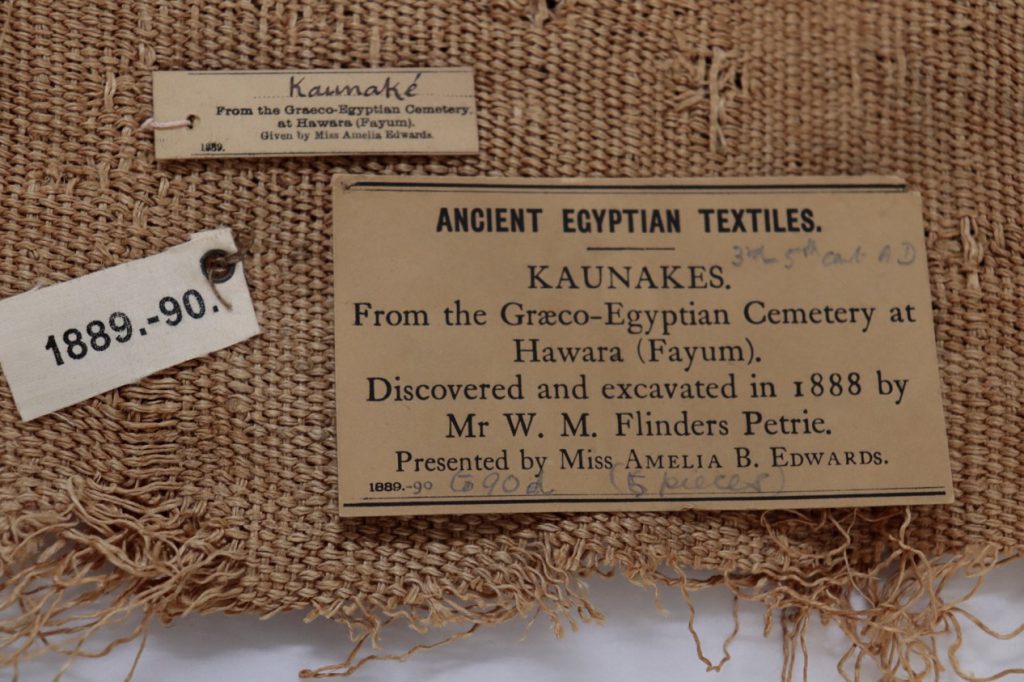

Amelia B Edwards was the co-founder of the Egypt Exploration Fund, a British charity formed to help fund the excavation and research of Egyptian archaeological sites. Interested individuals or museums could subscribe to the Fund and the money would then pay for archaeologists to travel to Egypt to conduct excavations. Under a colonial agreement at the time, after the first choice of finds had been selected by the Egyptian authorities, the excavator had permission to take the remainder with them to their country. The excavator’s share was distributed across the UK and the world. The AHRC-funded project Artefacts of Excavation has tracked objects from British excavations to 320 unique destinations in 26 countries. Amelia was an author and excellent speaker, skills she used to promote the Fund in Scotland when she undertook a lecture tour. In each place, she also left behind gifts of textiles from the Fund’s most recent excavations in the Faiyum. Four museums received these gifts: McLean Museum, The McManus, National Museums Scotland and Paisley Museum. Most decided to support the fund: success!

The fund is today called the Egypt Exploration Society, and you can still become a member.

Advertising artefacts: John Garstang’s pots

John Garstang was an archaeologist based at the University of Liverpool in the early 20th century. When he returned from excavations at Beni Hassan, he found that his share of objects included a lot of pots which were not of much interest to his wealthy backers. He decided to write a letter to the editor of The Times offering selections of the pottery as gifts to museums and educational institutions which were free to enter. This gave museums a chance to obtain objects that they might not usually have, and unsurprisingly, many museums replied to Garstang and he began sending packages of pottery. This included several museums in Scotland. Today, museums in Hawick, Edinburgh, Glasgow (The Hunterian and Glasgow Museums), Aberdeen, Perth, Paisley and North Lanarkshire care for objects which originated from this advert and Garstang’s other excavations. Though the pots were not seen as particularly collectable in the early 20th century, we can actually learn a lot from ceramics: what they contained, where they were made and what other objects were buried with them can all be researched, providing a better picture of ancient life. They are also one of the most important objects for dating burials, as styles changed over time in the same way that our great-grandparents crockery would be different to today’s. We shared some of this information when Discovering Ancient Egypt was held in Hawick, where some of Garstang’s pots were put on display, sharing their modern and ancient histories.

Many of the museums I worked with have created new displays, re-packed their collections, updated databases, developed new schools’ sessions, written new interpretation and so much more. It has been brilliant to see the enthusiasm for the subject and for the Egyptian collections in Scotland.

Although I can only share a few of the stories here, as part of the project we also made several short films, highlighting some of the collections across Scotland and the individuals who were key in their formation:

Scottish Museums and the Egypt Exploration Society

Ancient Egypt at the University of Aberdeen and Dr James Grant Bey

Ancient Egypt at the Hunterian Museum and Rev. Colin Campbell

Ancient Egypt at the McManus, Dundee and Rev. Colin Campbell

You can also find the whole review here, which will tell you about all the collections of ancient Egyptian material in Scotland. Each museum has its own section in the regional reports so you can find out what is in your own local area. There’s also some information about the history of collecting in Scotland, the historic archaeological distribution networks and lots and lots of information about donors and archaeological sites represented in these collections.

It has been fascinating to find out about all these Scottish collections, the objects and the stories were often new to me, so I hope you will also enjoy reading about them too!

The Ancient Egypt and East Asia National Programme has been made possible thanks to the generous support of the National Lottery Heritage Fund. Revealing Stories has been made possible thanks to the Esmée Fairbairn Collections Fund, delivered by the Museums Association.