Discovering Ancient Egypt a National Museums Scotland touring exhibition is currently on display in Hawick Museum in the Scottish Borders. It brings together objects and stories from National Museums Scotland along with those from Hawick’s own collections to give a unique insight into Scots’ fascination with ancient Egypt, and the nation’s contribution to Egyptology over the past 160 years.

The exhibition also highlights the changes in Egyptian archaeology over this time. Though some early collecting was reckless, increasing care was paid by excavators, recording their finds more scientifically and working in collaboration with Egyptian colleagues.

Alongside the stories of an archaeologist, an astronomer and an artist who all contributed to the national collection, there is a selection from the Scottish Borders’ only collection of ancient Egyptian objects! This is the story of how they came to be in Hawick.

Hawick Archaeological Society was founded in 1856 by six local men. The Society quickly began collecting objects from across the world to display in its new museum. Over the next fifty years, the members of the Society collected and donated objects to this museum project. In 1910, the current museum was opened, showcasing their archaeological and natural science collections.

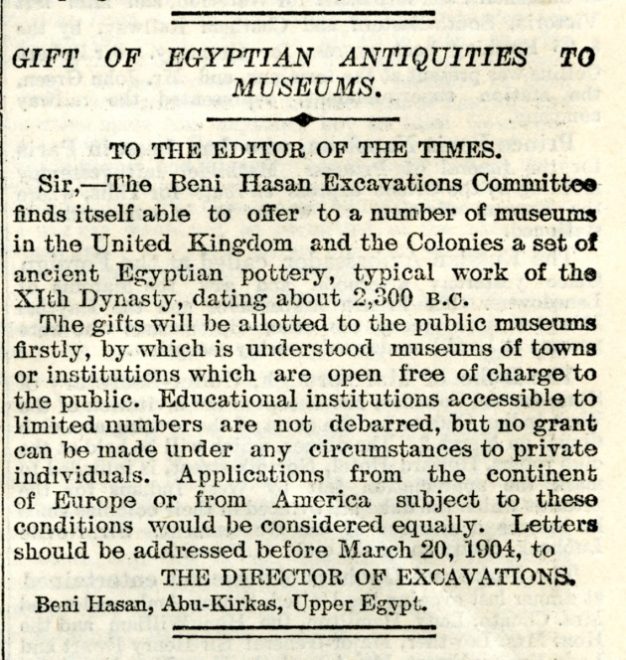

Before this time, a gap in the collection must have been noted by the secretary of the Society. He had also identified a way to fill this gap. In 1906, the Society responded to an advert in The Times offering a ‘set of Egyptian pottery’ to educational institutes, for only the cost of postage. Though the advert had originally been published in 1904, the excavator was able to help with their request and duly sent 38 ceramic vessels to Hawick in 1907.

The advert had been placed by the Liverpool-based archaeologist John Garstang. Born in Blackburn in 1876, Garstang went to university to study mathematics, but quickly became distracted by archaeology and the ancient world. Having joined Flinders Petrie, often referred to today as the ‘father of Egyptian archaeology’, on excavations in 1899, Garstang went on to run his own excavations in Egypt, Sudan, Turkey and Palestine. He was able to fund his work through the support of direct financial sponsors, many of whom were industrial magnates in North-West England. Garstang had permission to excavate from the Egyptian antiquities service, with the arrangement at the time being that the Egyptian government had the first choice of the objects found; the remainder could leave Egypt with the excavator to do with as they wished. This is how a large number of ancient Egyptian objects came to the UK.

In Garstang’s case, he distributed his share of the finds to his backers at an annual dinner, thanking them for their support and conducting a blind ballot to distribute crates of objects. This blind ballot ensured that no single sponsor could feel aggrieved at their received lot. After two seasons working at the site of Beni Hasan, Garstang and his team had excavated over 900 tombs and burial shafts. This left him with a large surplus of ceramics and other small objects which were often deemed uncollectible by his backers. Not at all a view that we would share today!

On Valentine’s Day 1904, The Times published the advertisement in letters to the editor. It stipulated that private individuals were barred from applying and that those eligible institutions who wished to apply should be ‘open free of charge to the public’. The replies came thick and fast! From his home in North Wales, Garstang’s excavation assistant Harold Jones began to arrange their transport. Over 100 institutions replied, leading to ceramic vessels being sent across the world, including museums in Scotland, Jamaica, New Zealand, India and Canada.

A few years later, this offer must have stuck in the mind of some of the members of the Hawick Archaeological Society, leading to their contacting Garstang. Though unable to share material from Beni Hasan, he had just conducted successful excavations in Esna in southern Egypt. 38 ceramic vessels were sent to Hawick and put on display when the new museum opened.

Over the course of the 20th century, their provenance information was lost, but it was re-identified in 2006 as part of a Museums Association and British Museum project. Thanks to the unique marking system applied to the objects after their excavation, noting down the site and tomb number, Egyptologists can identify the origin of such objects, allowing us to piece together what was buried in each tomb.

For example, looking at Esna burial 305, though only a few vessels are to be found in Hawick, there is a selection of metal hair rings and other objects in the collections of National Museums Liverpool.

We are also able to think about the lives of the ancient individuals. Two vessels on display come from Esna tomb 247, the burial of a man called Montuhotep. Thanks to a stela (a stone monument) in the Garstang Museum of Archaeology, University of Liverpool we are able to find out his mother’s name, Aarut. Though we don’t know what he did for a living, we know that Montuhotep was married to a woman called Bit and had a son, also called Montuhotep. His burial contained 11 models of the Nile perch fish, which was seen as sacred to the local goddess Neith, so perhaps he was particularly religious.

We can also determine the name of the owner of an offering plate that is on display from a different burial at Esna. Senebef held the title ‘Chief of the Tens of Upper Egypt’, which may have been a type of judge. Interestingly, his brother Reseneb also held this title. Senebef’s burial showed his wealth, and included eye make-up pots, copper tweezers, seal stones and gold rings. The offering plate would have been loaded up with food to sustain Senebef’s soul for eternity.

These ceramics may seem unassuming, but they can teach us a lot about the lives of the ancient Egyptians, as well as helping us learn about the history of archaeology.

Developed by National Museums Scotland with funding from The National Lottery Heritage Fund, Discovering Ancient Egypt is part of our national programme to extend the reach and impact of the new Ancient Egypt Rediscovered and Exploring East Asia galleries to audiences across Scotland. The review of Hawick Museum’s ancient Egyptian collection is supported by the Collections Fund – delivered by the Museums Association.

Discovering Ancient Egypt will be at:

Hawick Museum, Museum until 2 June

Montrose Museum, Montrose 8 June – 7 September

Baird Institute, Cumnock 14 September – 14 December