What do you picture when you think of the ‘Dark Age’? The common perception the phrase conjures is simple living and hardship. However, the sheer number of inscribed objects from this period paint another picture. Through new research methods, we are uncovering the multiple voices of early medieval Britain and evidence of a multi-lingual, even multi-literate society. There are big questions relevant to our early medieval collections, and one that has animated me since I began here last year is the evidence for literacy.

The Glenmorangie Research Project is studying the material culture of the ninth to twelfth centuries in Scotland, when evidence for literacy is more abundant than most people realize. It is true that there are precious few manuscripts written in Scotland which pre-date the twelfth century. But only a privileged few would ever have had access to such texts. Inscribed objects give another perspective, of people with the ability to read and write outside the monastery. Inscribed stone monuments are still likely to have been made by the elites of society, but exposed a larger audience to the technology of writing. Personal objects like tools and amulets with written messages represent the use of technology at an individual level.

Languages in early medieval Scotland

What I find endlessly fascinating is the number of different alphabets and languages these inscriptions represent. In what we now call Scotland, there are no fewer than five scripts used in the ninth to twelfth centuries. These largely appear on stone monuments, but also on a small number of portable objects. They are often associated with ethnic groups, like ‘Irish’ oghams, or ‘Norse’ runes, but the situation is rather messier, so we should try to describe them in neutral terms according to their characters. The five main scripts used in early medieval Scotland were:

- Latin

- Pictish symbols

- Ogham

- Futhorc (also known as Anglo-Saxon runes)

- Younger Futhark (also known as Scandinavian or Old Norse runes)

If we are being completist, we might also include two other alphabets which were probably not used regularly or even legible to most who saw them. Greek characters appear in Christian iconography in the sixth to seventh centuries, for instance on the crosses of Kirkmadrine in the Rhins of Galloway. The Kufic script, used to write in Arabic, appears on silver dirham coins which occur in some Viking-age silver hoards in Scotland and beyond.

Prehistoric origins

One striking aspect of this list is that, except for the Latin and Greek characters which have their origin in antiquity, all these scripts were developed in the first millennium AD. Ogham, runes, and now possibly the Pictish symbols as well, were invented in the early centuries AD beyond the furthest reaches of the Roman Empire. They were likely inspired by knowledge of Latin writing but developed to capture the sounds and concepts of indigenous languages. It shows an intellectual capacity and, importantly, the ability to communicate and agree across wide areas, which the Roman accounts of these peoples would never have allowed us to see.

Importantly, they represent ‘prehistoric’ or ‘iron age’ technologies which carried on in use for centuries, in some cases into the second millennium. They show just how arbitrary our division of time into history and prehistory is for us today, based on the survival of written accounts as the critical box to be ticked on the path to ‘civilisation’.

Overlap, exchange and adaptation

The story these scripts tell is one of a multilingual, and even multi-literate, period – hardly a dark age. And while these forms of writing have been studied as separate traditions, there is copious evidence for overlap, exchange and adaptation. So for instance, the ogham script was developed in Ireland and is most strongly linked with the Gaelic language. Yet oghams from Scotland were used to write in both Gaelic and Pictish languages, and in fact, the majority of oghams from Scotland come from the northeast rather than the parts nearest to Ireland. The difficulty lies in dating these (or any) inscriptions where we can only partially read or understand them. The careful and rigorous work of Dr Katherine Forsyth (University of Glasgow), however, has identified examples of oghams which postdate the Viking incursions of the ninth century, and signs of influence from runic writing into ogham script in Scotland. In short, ogham was able to move across languages, regional traditions, and yes, that old chestnut, ‘cultures’.

Given the difficulties in reading, dating and contextualising these inscribed objects, it makes the best sense to approach them together as evidence for literacy in the period, rather than try to separate them as the product of ethnically-defined actors like ‘Vikings’ and ‘Picts’. If we look at the evidence for literacy as a whole, we instead see a more interesting picture of early medieval Britain. Multilingualism is a theme running through the (pre)history of Britain and Ireland, even while unified kingdoms began to form later in the medieval period. The collection of National Museums Scotland provides some of the best evidence for the interplay of these multiple voices in our history.

Uncovering evidence of multilingualism

One of my current projects is uncovering evidence of multilingualism using a technique known as Groove analysis. This is a statistical technique developed by Laila Kitzler Åhfeldt for the study of Swedish runestones. By laser-scanning thousands of runic inscriptions, she has been able to demonstrate the existence of regional ‘schools’ by algorithmically analysing the grooves of individual letters – in effect, seeing different kinds of ‘handwriting’ in stone. This method has never been applied to the corpus of runic inscriptions outside of Scandinavia.

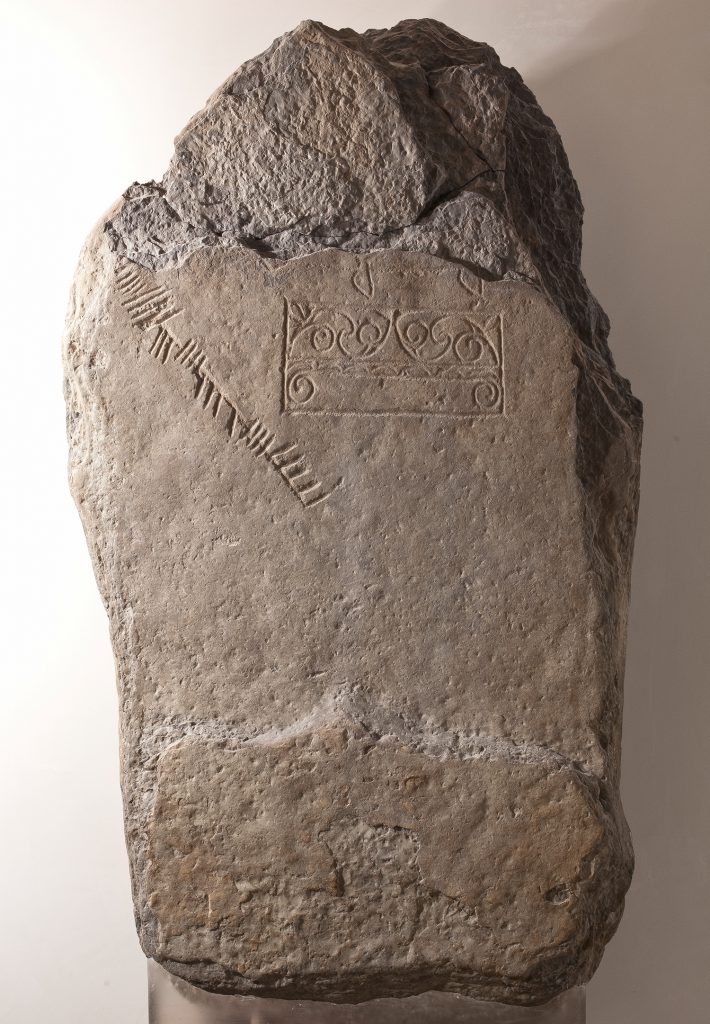

In Scotland, we have an unprecedented opportunity to test runes alongside other writing systems. Working on our inscribed objects with experts outside the museum, we realized that if we were to apply Laila’s algorithmic technique to runes, it would be criminal not to test the other scripts which appear in the same areas. In fact, there are two sites in Scotland where multiple scripts seem to coexist: the Brough of Birsay, Orkney and Cunningsburgh, Shetland have stones marked with either Pictish symbols, ogham or runes. They provide an opportunity not only to digitally document our early medieval collections in unprecedented detail, but also to test whether empirical data could be added toward the tough questions raised by these fragments of writing.

Together with Alex Sanmark, Reader in Medieval Archaeology at the University of the Highlands and Islands, we put together an innovative pilot project to study these three ‘vernacular’ scripts – symbols, ogham and runes – which characterise literacy in early medieval Scotland. Together we secured generous funding from the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland and the Scottish Medievalists: Society for Scottish Medieval and Renaissance Studies Barrow Award to support the work of Laila Kitzler Åhfeldt (Swedish Heritage Board) and Henrik Zedig (Länsstyrelsen Västra Götaland, Sweden). In one lightning-fast week, we were able to laser scan all the inscribed stones from the Brough of Birsay and Cunningsburgh, and several others for context. It involved travel from Edinburgh to Orkney to Shetland, as the stones are currently shared between the National Museum, Historic Environment Scotland, Orkney Museum and Shetland Museum.

This is all part of a larger push which the Glenmorangie Research Project is making toward improving our own collections regarding early medieval literacy, including new photography, improved catalogue entries, and factsheets. Stay tuned for more news and more online resources over the coming year.

Glenmorangie Research Project

BBC News Story: Scanners throw laser light on the ‘dark ages’ in Orkney