Each week I get to immerse myself in National Museums Scotland’s UK moth collection. As a volunteer I am going through the drawers, putting the details of what is there onto a database – at times perhaps a bit tedious, but the perfect excuse to spend time looking at an impressive variety of moths caught from around the UK.

I’ve encountered some of the tiniest, microscopically beautiful, micro-moths; worked through drawers of plump-bodied hawk moths; and learned more about the (seemingly forever changing) systematics of Lepidoptera.

My interest in moths goes back many years, and I spend a lot of time recording them out in the field. In the museum collection there are some moths I will probably never see in the UK, some that bring back a joyful memory of discovery, and plenty to add to my ever-increasing wish list.

Small but beautiful: the metallic-winged Longhorn Moth, Adela reaumurella.

Emperor moths, an impressive day-flying moth most often found on bogs and moors in Scotland.

The UK butterfly and moth collection takes up 101 cabinets of the entomological collections. Each cabinet has 15 drawers and in these lie rows and rows of (mostly) well-curated specimens, the oldest dating back to 1800s. I’m about three-quarters of the way through and, with the contribution of a couple of other volunteers, around 135,000 specimens have now been documented on the database. But even when I get to the end of this, the work is not done. There are shelves containing boxes of “assorted moths” which need to be assessed, documented, and incorporated. Recently a large collection was bequeathed to the department. Fantastic to have, but to become a useful resource its contents needs to be indexed. The database entries will not only make it easy to retrieve information about what is in the collections, but it should also make it straightforward for anyone wanting to look at a particular species to know exactly where it is.

Insect cabinets that contain drawers of pinned moths.

A drawer of Convolvulus Hawk moths.

As well as getting to know some of our native moths better, I have another interest in going through the museum’s moth collections. About 100 years ago Alice Blanche Balfour (1850-1936), pursued moths in and around her East Lothian Estate at Whittingehame, close to East Linton and close to where I live and do much of my moth trapping now. Alice never married but ended up managing the Estate for her bachelor brother (Arthur Balfour the Politician and Prime Minister) and as a result, spent almost all her life-based in this corner of East Lothian. Domestic duty took up a great deal of her time, but even so, she made notable achievements in science, art and travel.

Moths seem to have been the focus of her natural history interests and her well-curated East Lothian specimens are now housed in the drawers of the UK moth collection at National Museums Scotland. She came across some enviable species – Portland Moth, Stout Dart, Mallow; moths to dream for! – and her efforts have certainly bolstered the East Lothian moth list. A hard act to follow.

Notebooks and correspondence form part of the collection, helping to bring her moth catching endeavours to life. Leafing through these notebooks got me wondering… What was it like to be a female moth enthusiast a hundred years ago? How did she find her moths? How does it compare to my own ‘modern-day’ experiences? And so a personal moth project for 2019 was born: Discovering the Moths of Whittingehame: following in the footsteps of Alice Blanche Balfour.

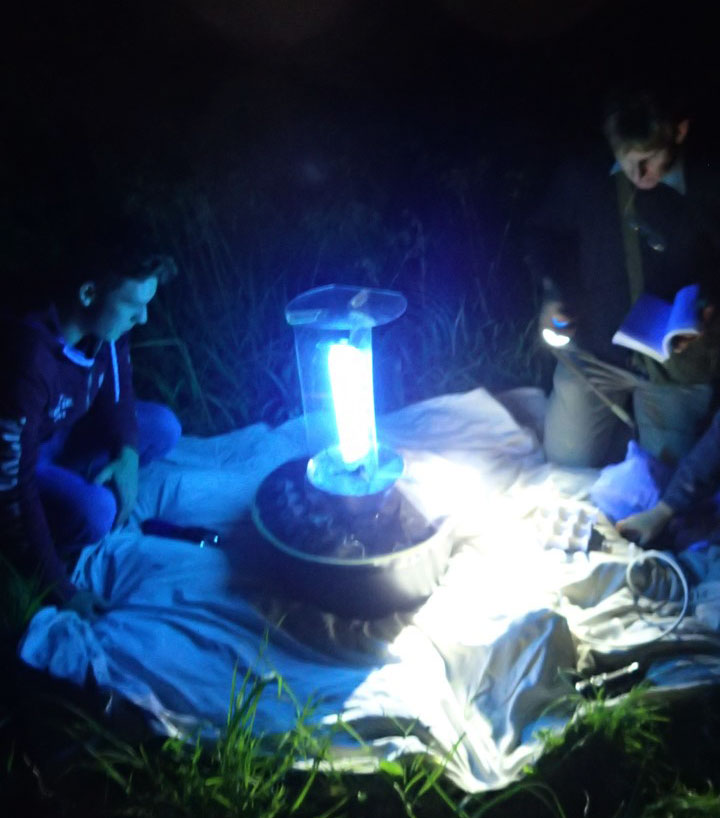

I have permission from the current landowner (Alice Balfour’s great-great-nephew) to set light traps on Whittingehame Estate, and in combination with occasional trips to some of the other places she frequented, I will endeavour to compare our mothy finds. Of course, I could never expect to find exactly the same species that Alice did: not only have moth distributions changed in the last 100 years (there are both winners and losers), but the methods of finding them are also changed – notably with light trapping becoming more straightforward and effective. Nevertheless, it will be interesting to see how much our species lists overlap and in the process discover more about the pursuit of moths in the late Victorian/early Edwardian era.

A light trap set in the arboretum at Whittingehame in February.

Part of the arboretum at Whittingehame in May.

Alice lived and moved in quite different circles to my own and society as a whole has changed, particularly for women, in the last century. Despite this, looking through her diaries and papers I’m starting to realise that the motivations, frustrations and joys she had from her interest in moths are not so very different from mine. She complains of having to entertain visitors instead of getting out with her net; she got excited by finding new species on home turf; she despaired at the encroachment of golf courses and ‘cultivation’ on the countryside.

Light trapping can become a bit of a list-making process, simply recording what is there and moving on. Using the museum collections to find out more about Alice Balfour’s moths has given my East Lothian moth trapping a new dimension, and added a personality to the historical species list of my home county.

Find out more about my exploration of Alice Balfour’s collection on my Rediscovering the moths of Whittingehame blog.

More information about the fascinating world of moths and how to help them can be found at Butterfly Conservation.