My first three months as Glenmorangie Research Fellow have been a process of immersion. Seeing the early medieval period from the perspective of artefacts has been like learning a new language. And getting to grips with the massive National Collection can sometimes feel like trying to read a phone book in that new language.

In order to get the stories out of it, I have been asking questions around a single artefact at a time. To give you a glimpse of my process, I will take some examples of artefacts I have been researching that, when taken together, can weave entirely new tales.

My research project is on the creation of Scotland in AD 800-1200, and anything in our collections from this period is part of the story. Perhaps the most dramatic change which defines this period is the opening up of the seaways by improved shipbuilding technology. These fast new ships were famously introduced to these islands by Viking raiders, but long-distance seafaring became a way of life thereafter. Orkney and Shetland were now at the centre of a trade network reaching from Greenland to the Baltic and beyond.

Through this network came exotic materials like walrus ivory, famously used to create the Lewis Chessmen, and fresh silver from the Byzantine and Arab worlds. As contacts broadened, everything from dress to diet was transformed. It is hard not to think of the beasts rendered on the Jarlshof bone pins (above) as dragons, evocative of the edges of the known world in maps from a later age of seafaring.

It got me thinking about what it meant for people in the Northern Isles of Scotland, whose lives were already spent facing the sea, to come face to face with strange people and creatures from far-off lands. Was the sea now tamed, a former wilderness lost?

Earlier Pictish art had numerous fish-tailed creatures, sometimes devouring human figures, sometimes even merging into hybrid creatures. But even as the seaways became more familiar, sea creatures never stopped being mysterious and fearsome.

A little-known carved stone slab from Jarlshof (above), dated 10-11th centuries, bears a hybrid of a dragon and a seahorse in a Scandinavian style, showing that such monsters remained a part of the northern thought-world. The purpose of this carving is unknown, but it may continue an earlier tradition of majestic wild animals depicted in stone grave markers at northern power centres like the Brough of Birsay.

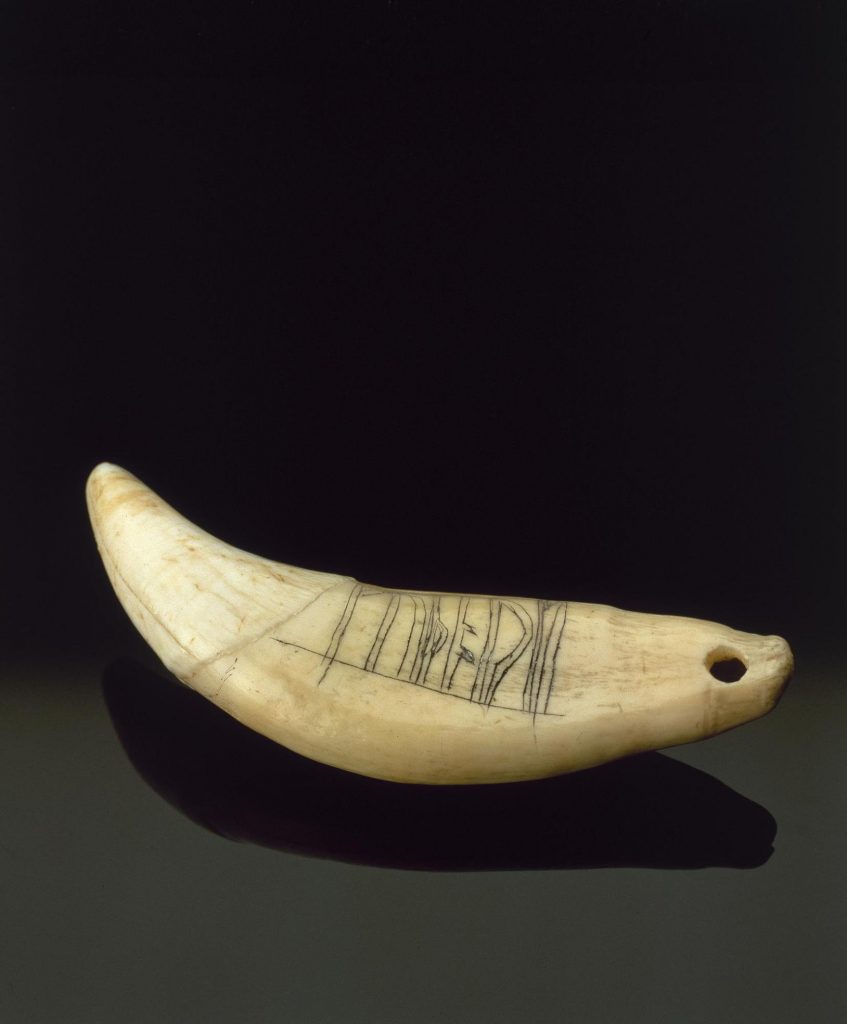

Change did not come only for the indigenous people. My new favourite object is from the Brough of Birsay off the Orkney mainland. This former Pictish power centre was colonised in the Viking Age, and from one of the early Norse middens came a perforated bear tooth with a runic inscription. The inscription seems to be amuletic, reading FUTHARK, the runic equivalent of writing ABCDEFG.

It is doubly interesting that it is a bear tooth, given that it will likely have been centuries since a bear roamed the sparsely forested landscapes of Orkney. This pendant was almost certainly brought from a foreign land, and used within a Norse-speaking context. I have yet to find another example with an inscription.

Bears were certainly being hunted for their pelts at this time elsewhere in the Scandinavian world. As supply increased, bears were commodified, and maybe somewhat demystified. By the Viking Age, bear tooth pendants like this one were rare everywhere except in Finland, Estonia and Latvia, where bear hunting was a core part of the economy.

They were generally found in female or child graves, and have been thought to be amulets for fertility or protection. This is the only one of its kind from Scotland, and the only inscribed example, so it is unlikely to have been used in the same way as other examples. We are exploring the possibility of doing further tests on this rare artefact to pinpoint its source, but it will be difficult to do so without damaging it.

All this just goes to show that in an age of increased exploration, the wilderness was not ‘tamed’, it was expanded. As the seaways opened up, new and unknown horizons were introduced to people in Scotland.

Different visions of the world were brought together by the encounter between people and exotic materials. The parts of the environment we now see as ‘natural resources’ were vibrant, animate realms, at once wondrous and dangerous. The artefacts reveal more complicated ways of seeing the past beyond Christian and pagan, foreign and native.

The Glenmorangie Research Project aims to extend our understanding of Scotland’s Early Medieval past and was established in 2008 following a partnership between National Museums Scotland and The Glenmorangie Company.

Scotland’s Early Silver exhibition is touring Scotland until March 2019 and follows three years of research supported by The Glenmorangie Company.