Written with Irene Kirkwood, Textile Conservator

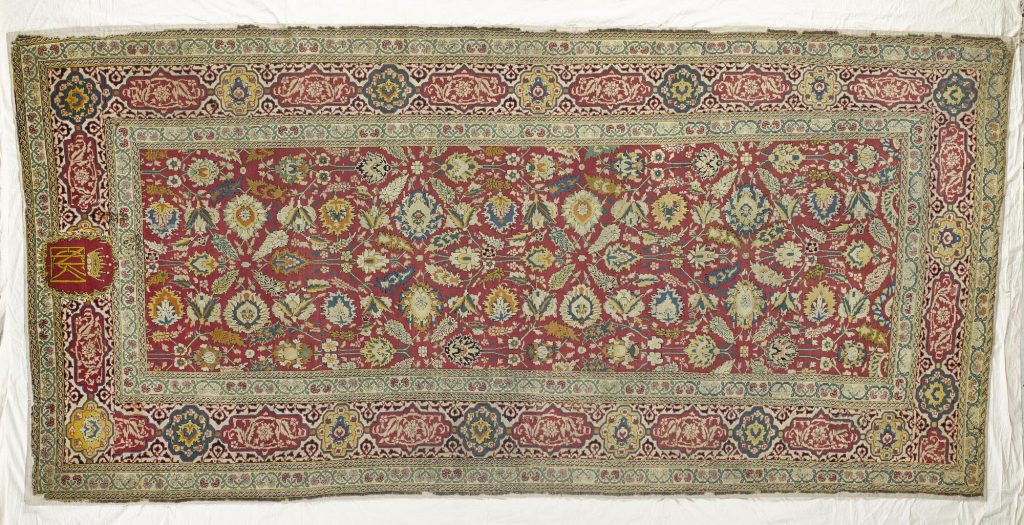

This rare 17th-century carpet, shown here before conservation treatment, was acquired by National Museums Scotland in 1980. The carpet is hand-knotted, with a wool pile on a woven hemp ground and measures 5277mm x 2460mm. It is thought to have been used as a table cover rather than a floor carpet, and is believed to have been made in England, imitating carpets imported from Turkey.

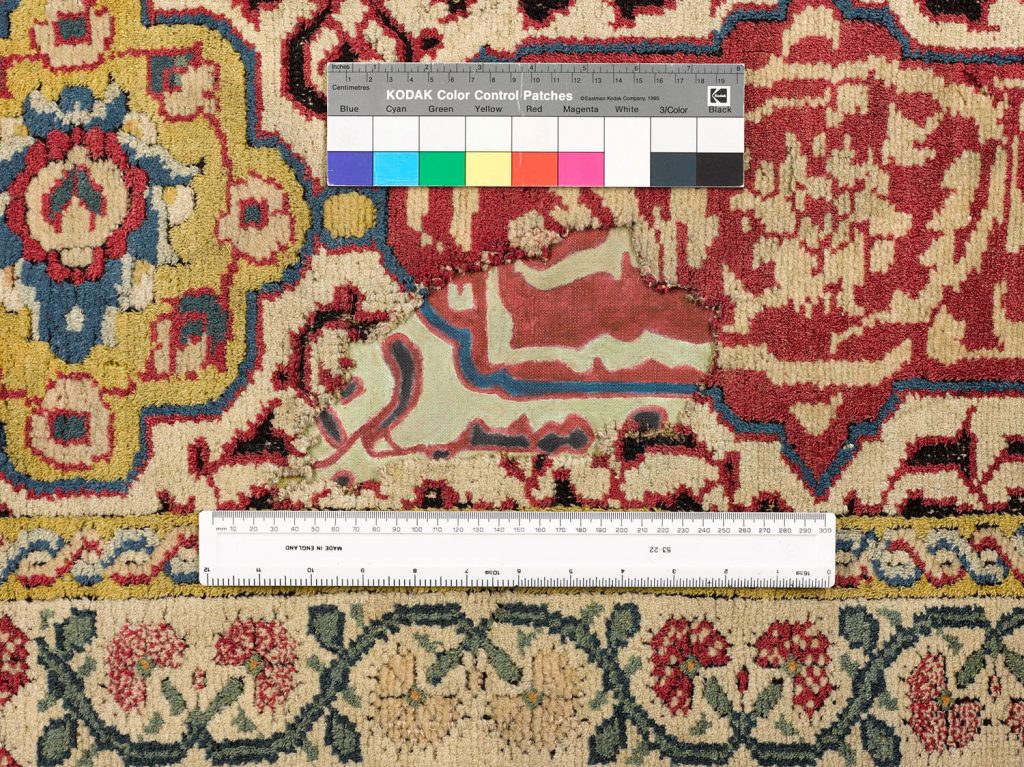

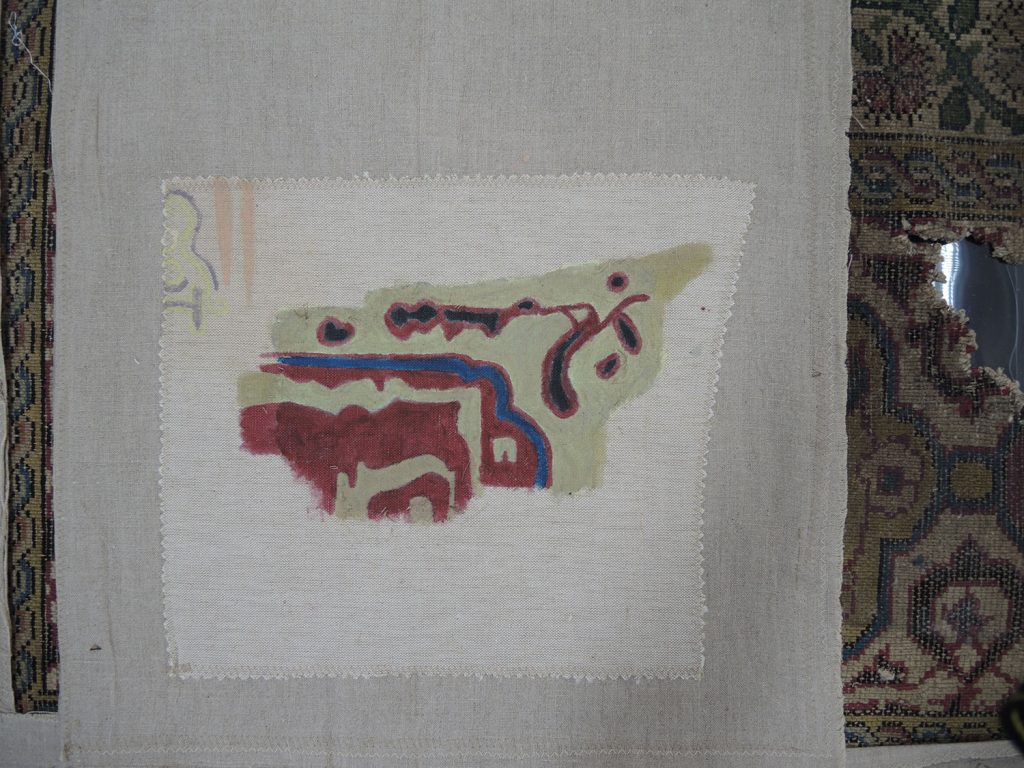

The carpet was conserved in the past to enable it to be displayed in two short exhibitions. This involved providing support to the weak and damaged edges by stitching onto linen fabric. A large hole in one of the wide side borders had been infilled with a linen support patch onto which the design had been hand-painted with fabric paints. The patch was then stitched in place on the reverse of the carpet.

Since then technology has moved on and in 2016, developments in digital printing gave the conservators the opportunity to replace the hand painted patch with a digitally printed one, giving a much more realistic depiction of the pattern.

To begin this part of the process, conservators contacted the Centre for Advanced Textiles (CAT) in Glasgow, who specialise in digital printing technology. Whilst their usual remit is with contemporary textile print design, they were happy to bring their expertise to this project and work with conservators at National Museums Scotland to produce a colour-matched, scaled infill patch for the carpet. Digital images were taken of a similar patterned section of the carpet by our photographers so that computer-aided design could be used.

The process began with discussions between the CAT printers and our conservators about the requirements for the patch. Texture was the starting point, as an important feature of infill support patches is that the cloth used has a similar weight and surface appearance to the historic object it is being matched with. Contrary to traditional patches, where the texture of the support cloth needs to be similar to the object in order to blend in, we were advised that the carpet pile would be reproduced most faithfully on a flat fabric rather than a brushed (napped) cloth, as the print image would probably distort if delivered on an uneven surface. As the digital print reconstructs texture solely with the image, reproducing the depth and texture of the carpet pile is best accomplished on a fabric with a flat surface. We therefore choose cotton duck to print onto, a closely woven, strong plain weave cloth.

Other aspects to consider were scale and colour. Almost unavoidably, printing processes can incur minute dimensional changes to the printed cloth due to a variety of factors, including temperature, inks setting, and finishing processes. During tests, we found there was some incremental change to scale, but were able to incorporate this by careful pinning of the patch in situ to ease out any slight differences.

Colour matching was perhaps the hardest aspect of recreating the patch. Throughout the process, a series of printed samples were made with subtle manipulations of colour saturation, hue and contrast, until we reached the final version. The plain wool pile was the most difficult colour to achieve. Originally an undyed natural wool, it would have been a light browny-cream when new. As time has passed, grey dust, dirt and yellow-coloured degradation products have bonded with the fibres and this colour has changed to a variable grey/mid-brown. Three print runs, each with around 12 different versions of the patch, were necessary to achieve the best colour match.

We were very pleased with our final choice, and tremendously impressed with the work at the Centre for Advanced Textiles. And whilst the depth of the printed pile is illusory, still the digital image blends so successfully with the carpet it is hardly noticeable. As conservators, our aim is never to deceive the viewer, but to stabilise weak areas using visually sympathetic supports which can be distinguished from the original textile – if noticed.

The new patch was positioned behind the hole, lining up the pattern with the carpet as much as possible and stitched in place using a polyester thread. The reverse of the printed patch was then protected with a larger patch of linen.

Since this carpet would have been used to cover a table, it was considered important to display it to reflect this, as we are now more used to carpets on our floors. A specially built display case was commissioned, into which the carpet could be carefully unrolled.

The carpet is on display in the Art of Living gallery at the National Museum of Scotland, with an interactive display showing more about the process involved in preparing it for display. Visit and see if you can spot the digitally printed repair patch!