With The Tomb: Ancient Egyptian Burial exhibition currently on display at the National Museum of Scotland, I wanted to take the opportunity to discuss the popular misconception that ancient Egyptian tombs all contain curses. This idea became widespread due to the sensationalist journalism that followed the discovery of the tomb of Tutankhamun in 1922. The death of Lord Carnarvon in the months after the opening of the tomb fit well with the idea of a long dead Pharaoh wishing for retribution and of course produced great headlines.

The famous Edinburgh-born writer Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, the creator of Sherlock Holmes, amplified this further by suggesting that an “evil elemental” from the tomb was to blame for Carnarvon’s death, rather than blood poisoning and pneumonia. In 1892 Doyle had published a short story called “Lot no. 249”, which utilised the bandaged menace of a reanimated mummy as the protagonist, a representation which profoundly influenced horror films throughout the 20th century. While this superstition has endured, the reality of how the ancient Egyptians viewed their tombs and the afterlife is actually very different.

Building a tomb was a massive investment in time, wealth and effort. Those who could afford to plan for their death began to put those plans into action as soon as possible. The Egyptians saw the afterlife as a chance to live again, in a place called the “Field of Reeds”, a paradise styled on Egypt (think Egypt 2.0, where the crops grow tall and the sun always shines). The Egyptians saw the individual as a number of parts, their life force (ka) would reside in the tomb after death and needed to receive offerings to survive. Another part of the person, the ba (represented as a human-headed bird) was thought to fly about during the day, but also needed to return to the tomb for the night.

The tomb chapel, which was a public area separate from the burial chambers, provided a focus for the family of the deceased, who visited during festivals to provide offerings for their relatives, similar way to the way in which we might visit a cemetery on the anniversary of a loved one’s death. Being remembered was as important to the Egyptians as it is to us today. Bearing these considerations in mind, you can see why the Egyptians saw the preservation of their tombs as important and the modern concept of curses reflects the amount of effort put into the preparation for death.

As Egypt’s fortunes rose and fell, tombs would be forgotten and buried or reused and repurposed. Through archaeological excavations we are able to understand some of these processes which are explored in The Tomb. A number of texts also help us to explore ancient Egyptian attitudes towards tomb building and reuse. One famous example is known amongst Egyptologists simply as “A Ghost Story”. In the story a High Priest called Khonsuemhab meets an unhappy spirit called Niutbusemekh, who complains that despite his illustrious life serving the King, his tomb has been destroyed, and he asks that Khonsuemhab help him to build a new one. The High Priest agrees and sets out to find a site; sadly the end of the story is not preserved so we don’t get to hear whether Niutbusemekh was provided with a new home for eternity or not.

Actual written examples of tomb curses from ancient Egypt are quite rare. Those that survive generally follow an almost legal structure; that if you do something negative you will be punished. I would be more inclined to call them warnings – you wouldn’t call a modern “No Trespassing” sign a curse. One particularly fun example of a warning from the tomb of Penniut at Aniba warns that any negative behaviour will result in the individuals simply being “miserable”, others suggest that the transgressor will not achieve their desired afterlife, or simply warn that one bad turn results in another. This type of warning can be found throughout Egyptian legal texts, whereby a negative behaviour is equalled with a punitive measure, for example as an oath: “If I dispute this matter again, I will receive 100 lashes”; or in a will: “the children who have given me nothing, I will not give them any of my property”.

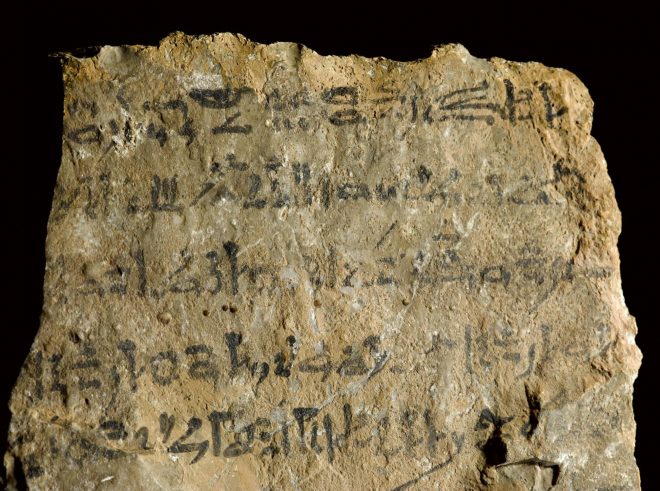

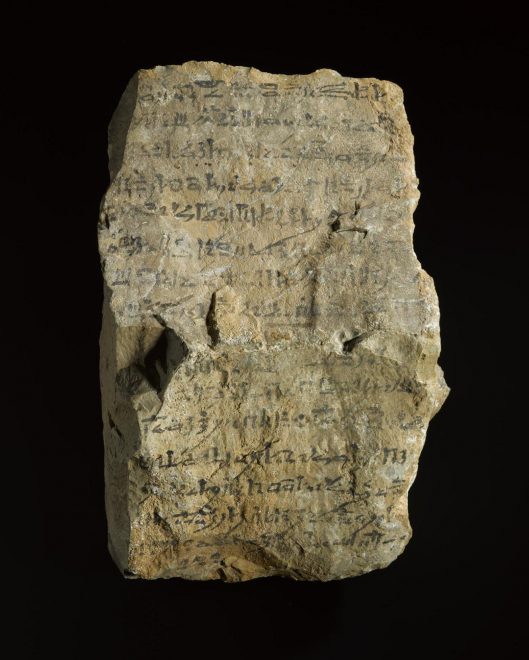

Within the collections of National Museums Scotland there is an inscription on a piece of limestone which provides another insight into the ancient Egyptian desire for the tomb to survive intact. The stone, which is around the size of a few bricks, was covered with a light wash to provide a clean surface for the inscription. Dated to between approximately 1295-1069 BC, the fifteen lines of the inscription implore visitors to the tomb in which it was placed to behave correctly, in a similar way to traditional inscriptions which ask for visitors to give offerings. The inscription is written in a script called hieratic, which was a shorthand form of Egyptian writing. To share this with you I have translated it below.

It opens:

“It is to you that I speak; all people who will find this tomb passage!”

The visitors are then warned:

“Watch out not to take (even) a pebble from within it outside. If you find this stone you shall <not> transgress against it.”

They are also reminded of the power of the deceased, who are referred to as gods:

“Indeed, the gods since (the time of) Pre, those who rest in [the midst] of the mountains gain strength every day (even though) their pebbles are dragged away.”

The reader is encouraged to find their own space to build their tomb and not encroach upon others’:

“Look for a place worthy of yourselves and rest in it, and do not constrict gods in their own houses, as every man is happy in his place and every man is glad in his house.”

The inscription ends with a final warning on behalf of the deified dead, written emphatically:

“As for he who will be sound, beware of forcefully removing this stone from its place.

As for he who covers it in its place, great lords of the west will reproach him very very very very very very very very much”

There are no threats of death or of spiritual vengeance; instead we see a well-written appeal towards good behaviour which would help protect the tomb and honour the memory of the deceased. Though perhaps the “Mummy’s Gentle Reproach” isn’t quite as snappy or headline grabbing.

Some further reading:

Luckhurst, R. (2012), The Mummy’s Curse: The True History of a Dark Fantasy, Oxford.

The Tomb: Ancient Egyptian Burial is at the National Museum of Scotland until 3 September 2017.

Sponsored by Shepherd and Wedderburn